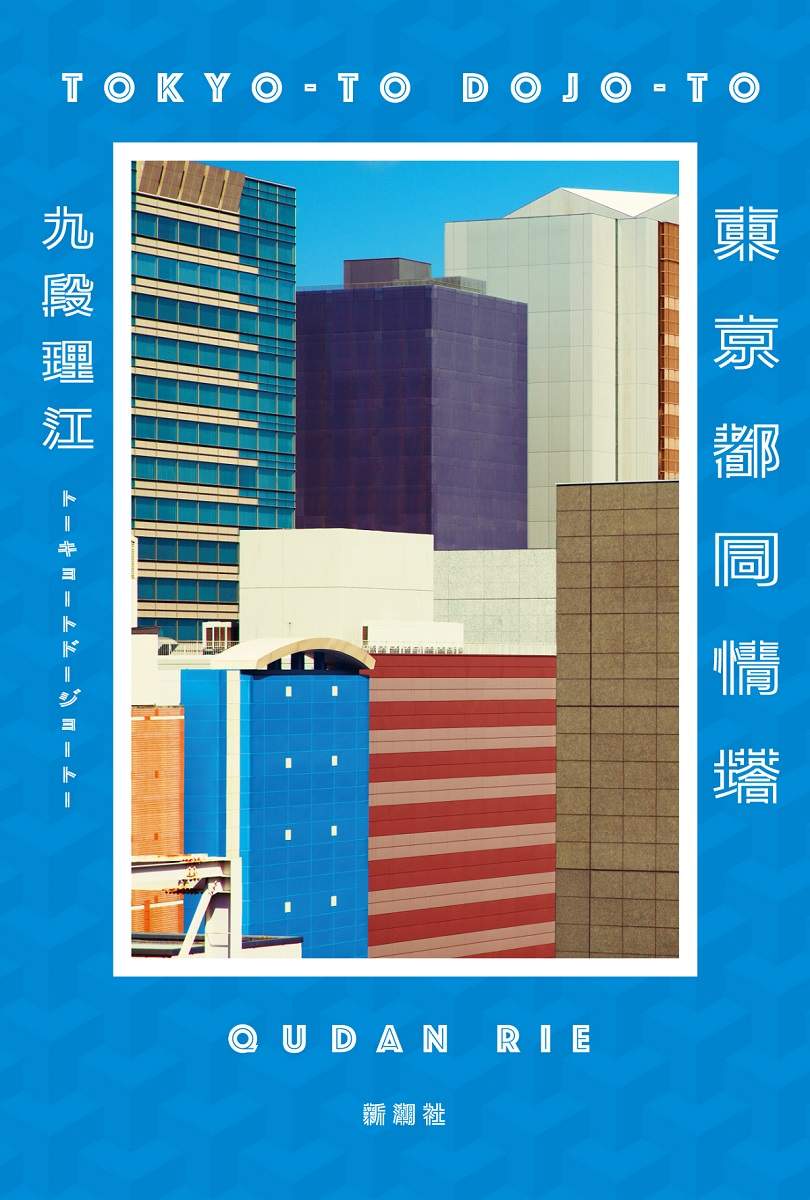

Prize-Winning Novelist Rie Qudan Finds AI Works Lacking in Human Originality; Latest Novel That Used AI, ‘Tokyo-to Dojo-to,’ Touches on Tech, Japanese Culture

The cover of “Tokyo-to Dojo-to” (“Sympathy Tower Tokyo”)

1:00 JST, June 17, 2024

Novelist Rie Qudan, who used AI to help her write the novel “Tokyo-to Dojo-to” (“Sympathy Tower Tokyo”), suggested in an interview with The Japan News in April that humans can create novelty in a way AI cannot.

The author does not mind her works being used to train AI. “I understand that there are people who are having a hard time after losing their jobs to AI,” she said, “but if my work can be used to help develop the technology then they can use anything they like.”

And yet, the technology is not all roses to Qudan. In her novel, the characters are sometimes frustrated by the AI model called AI-built, or feel pity for it. Takt, a young friend of protagonist Sara Machina, believes that being an AI must be very painful since it must keep stringing together words at the behest of others; it must keep pushing out unoriginal prose without knowing what it means or who is asking for it.

AI can already generate something close to a novel. Asked why people would write novels when such technology exists, Qudan said: “AI is obviously different from humans. No matter how much AI is improved to make it imitate humans, it can only learn from what humans have made, from old data.

“It seems to have difficulty producing new things with just calculations … I think novelty will be created by chance, or by incorporating something that AI can’t predict. I want to produce something new that hasn’t existed in the world. I think that is why people write novels.”

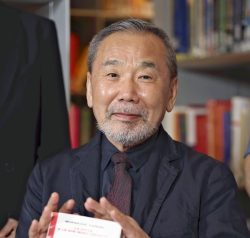

Rie Qudan speaks during an interview in Tokyo in April.

A new Tower of Babel

In “Sympathy Tower Tokyo,” the protagonist Machina designs a tower for prisoners, and in the process realizes how foreign words have eroded the Japanese language. Machina likens the project to the Tower of Babel myth, in which people were cursed to speak different languages from one another.

The leading advocate for the tower, a scholar of sociology and happiness studies, labels all criminals “Homo miserabilis” and calls non-criminals “Homo felix.” The Homo miserabilis, he says, are pitiful and deserve mercy. The project gets named “Sympathy Tower Tokyo,” an English phrase even in the Japanese text.

Surrounded by foreign words meant to curb discrimination and inequality, Machina comes to believe that the Japanese people want to abandon their language. She starts calling the tower “Tokyo-to Dojo-to,” a translation of the tower’s name into Japanese.

“I tried to dig a little deeper into the words that people use today and to incorporate them into my work,” said Qudan.

Asked why Japanese people use foreign words, she said, “I think Japanese value harmony with others … It seems like they want a word to have a wide range of meanings, that they don’t want to limit the meaning … I guess they’d like to show they’re harmless to others.”

Japan’s ‘beautiful lies’

The book also touches on the way Japanese people will sometimes go against their own feelings to avoid conflict. A foreign character argues that the Japanese are so used to telling “beautiful lies” that they are not even aware of the habit.

Qudan said she sees this in how Japanese people treat one of her friends from outside Japan. “Everyone talks publicly about embracing diversity, but I really feel like they don’t want him in their circle if they can avoid it,” she observed. “There is a disconnect between how they feel and how they act … But I’m not saying this is a bad thing. It’s also sort of where you find the kindness and charm of Japanese people.”

The book is scheduled to be released in English in the United Kingdom in 2025, and is set to be published in the United States and other Asian and European countries.

“This work is also a story about the Japanese language, so I hope people outside Japan are interested by the language,” Qudan said. “I hope that they will discover something new about it from their own point of view.”

Japan’s ‘quirky’ women writers find readers in West

Japanese women novelists have been gaining attention in the United States and Europe in recent years, with some winning or making the shortlist for literary awards there.

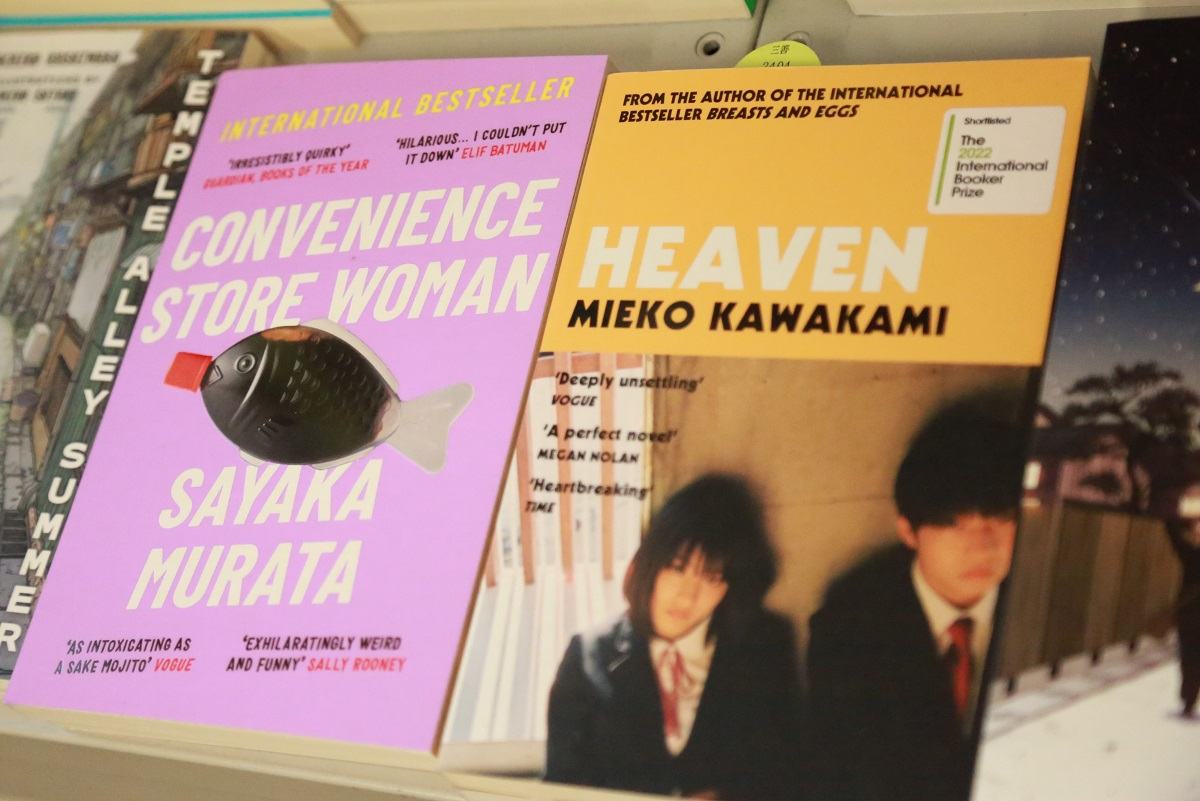

Yoko Tawada won the U.S. National Book Awards for Translated Literature in 2018, and Yu Miri won in 2020. In 2022, a novel by Mieko Kawakami was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize. Another of Kawakami’s works was shortlisted for the U.S. National Book Critics Circle Awards in 2023. Sayaka Murata’s “Convenience Store Woman,” which won the 2016 Akutagawa Prize, has also proved a global hit.

Naomi Mizuno, who mediates between foreign and Japanese publishers at Tuttle-Mori Agency, Inc., says she has been asked by Western publishers about “quirky” novels by Japanese female novelists before, but in recent years the requests have ballooned.

“Female writers often take everyday issues as their subject, and this may make it easier for non-Japanese readers to relate to the situation,” said Mizuno.

She also pointed to the surging demand for “charming, feel-good stories,” regardless of the novelist’s gender. “I think publishers now have broader interests, are interested in more types of works. They want content that is somehow Japanese, but also with some timeless and universal element.”

According to Shinchosha, the Japanese publisher for Rie Qudan’s “Tokyo-to Dojo-to” (“Sympathy Tower Tokyo”), the book will be published worldwide. The company said it received an unusual volume of publication offers from overseas.

Mizuno, who is also involved in the book’s global release, said, “‘Sympathy Tower Tokyo’ discusses our relationship with AI and social pressure to conform. These are issues not only for Japan, but are globally common trends today, and the novel questions how we deal with them. I think this will be highly rated on the international market.”

Books by Sayaka Murata and Mieko Kawakami are seen at the Maruzen Marunouchi Main Store in Tokyo in May.

Rie Qudan

Qudan was born in Saitama in 1990. After working as a teacher at a vocational school and as an employee at a used book store, she made her debut in 2021 with “Warui Ongaku” (Bad music), which won the Bungakukai new writers award. In 2023, “Schoolgirl” won the Cultural Affairs Agency’s Geijutsu-sensho award for new writers, and “Shiwokakuuma” (Poetry horses) won the Noma Bungei award for new writers. “Tokyo-to Dojo-to” (“Sympathy Tower Tokyo”) won the Akutagawa Prize in January 2024.

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Chofu, Tokyo; Unique, Surreal Works Draw Steady Crowds

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan