12-Day War on Iran by Israel, U.S. Had No Winners; Tehran’s Nuclear Efforts Likely to Go On

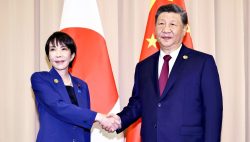

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian visits the Iranian Atomic Energy Organization in Tehran on Nov. 2, 2025.

8:00 JST, November 22, 2025

I spent three years in Tehran as the Iran correspondent for The Yomiuri Shimbun, starting in 2015 — the year a nuclear deal was reached with the United States and others to lift sanctions and integrate Iran into the global economy.

On reporting trips to Egypt in those days, local people in that country often asked me the same simple question: “You’re visiting from Iran? Tell me, is Iran really that powerful?”

Significant attention was being paid to Iran, a major non-Arab Islamic power with which Egypt had no diplomatic ties. Under the then new deal, Iran was expected to see growth in its economic power.

Nearly 10 years have passed since then. The nuclear deal has essentially collapsed. In June, Iran had its military vulnerabilities exposed during the military exchanges with Israel described as a 12-day war. Iran’s air defenses were breached, and its capital faced daily missile strikes. Top regime officials were systematically targeted and assassinated. Israel and the United States bombed Iranian nuclear facilities, with U.S. President Donald Trump claiming three sites had been “completely destroyed.”

“I never imagined it would come to this.” That’s what an Iranian acquaintance in Japan told me one day in June, just as the air raids began.

Nevertheless, my answer to the question of whether Iran is powerful today is “yes and no.” While Iran certainly showed its vulnerability, it could also be argued that Israel and the United States were able to go only so far. Iran’s land area is 75 times larger than that of Israel, and its population is nine times larger. Israel, with its troops numbering just under 170,000, would likely have no way to deploy against Iran, which possesses 610,000 troops. The same holds true even for the United States, which carries the bitter memory of the post-war quagmire in Iraq.

Takuya Murakami, the senior fellow at the Institute for Middle East Strategic Studies in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, offers the analysis that “Iran’s prestige was damaged in the 12-day war, but it demonstrated the regime’s resilience.”

Murakami stated: “The issue of whether Iran’s nuclear capability has been lost is separate from facilities being destroyed or not. Even if all the centrifuges used for uranium enrichment were destroyed, as long as Iran retains its manufacturing capability, they can simply build new ones. The stockpiled enriched uranium was reportedly moved out of the nuclear facility before the attacks. In a fundamental sense, Iran’s nuclear capability has not been lost.”

Murakami’s analysis is also that Iran’s ground forces remain largely intact. Although top commanders and officials were assassinated, a bureaucratic organization can replace its personnel, thus preventing prolonged paralysis in the chain of command.

Indeed, according to Reuters, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian vowed on Nov. 2 that his country will rebuild its nuclear sites “stronger than before.”

“Destroying buildings and factories will not create a problem for us,” he said.

Richard Haass, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, argues in the Fall 2025 issue of the Yomiuri Quarterly that Iran is taking the initiative in the current Middle East crisis.

He wrote that Israel’s attack on Iran constituted Phase 1, that U.S. involvement in the attack was Phase 2, and that “the Middle East crisis has now entered Phase 3. In the past two phases, Israel and the United States held the initiative. But that has now shifted to Iran.”

Haass suggested that the efforts to destroy nuclear facilities may have failed and that overthrowing the Iranian regime would be difficult. Regarding Iran’s next steps, he predicted that it was unlikely to immediately launch actions such as disrupting maritime transport through proxies like the Houthi in Yemen. Instead, he anticipated that Iran’s leadership would focus on strengthening its domestic system and ensuring its survival.

The background to the 12-day war was Israel’s heightened perception of the threat posed by Iran’s nuclear program. At the time, Iran was believed to possess more than 400 kilograms of uranium enriched up to 60% purity, which might be enough for nine nuclear bombs if enriched further. However, Iran was simultaneously engaged in repeated negotiations with the United States over restrictions on its nuclear program. Israel’s attack frustrated these negotiations.

Iran’s nuclear program, a root issue of the current Middle East crisis, remains entirely unresolved.

This issue was uncovered in 2002 when members of the Iranian opposition abroad exposed Tehran’s secret uranium enrichment program. In the world order led by the United States, only a handful of nonnuclear states, such as Japan and Germany, are permitted to enrich uranium. Suspicions that Iran was pursuing nuclear weapons grew, and the U.N. Security Council imposed successive sanctions to halt its nuclear development. The 2015 nuclear deal was the diplomatic solution reached after years of negotiations with Iran. Its core provision was the lifting of sanctions against Iran in exchange for Iran significantly curbing its nuclear development and accepting stronger IAEA inspections.

However, the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from this agreement in 2018, throwing the situation into disarray. After a year, Iran announced it would suspend its own commitments under the deal as a countermeasure and accelerated its nuclear development. Three other parties to the nuclear deal — Britain, Germany and France — pulled the trigger this summer, just before the deadline, to invoke procedures to revive all past U.N. sanctions against Iran, causing the nuclear deal framework to collapse after 10 years.

The IAEA is unable to monitor Iran’s nuclear development, creating a situation reminiscent of 2002. The longer this “gap period” during which Iran cannot be checked persists, the stronger suspicions in the international community about Iran’s nuclear armament program will become.

Iran denies any intent to develop nuclear weapons. Unlike North Korea, which withdrew from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and acquired nuclear weapons, Iran’s technology is said not to have reached full weapon-making capability. Iran’s insistence on pursuing nuclear development is largely driven by its intention to use it as a bargaining chip in diplomatic negotiations. Iran seeks national prosperity, yet U.S. economic sanctions shackle its progress, preventing it from attracting the foreign investment needed to develop its largely untapped natural resources. It has pursued “brinkmanship diplomacy,” using restraint on nuclear development as leverage to extract concessions and lift U.S. sanctions. The nuclear deal initially went as planned. But the latest acts have provoked military actions from Israel and the United States.

Within Iran, there were no visible movements calling for regime change in response to the Israeli and U.S. attacks. However, the regime does not enjoy solid public support. Rather, public discontent has reached the boiling point due to inflation and a sense of social stagnation.

I have heard the voices of despair from Iranians, saying such things as, “I can’t envision my future.”

Kazuto Suzuki, a University of Tokyo professor who served on the Panel of Experts for the Iranian Sanctions Committee under the UNSC, said: “Had the United States not withdrawn from the nuclear deal, I believe a different future was possible. That withdrawal threw everything off course.”

He continued: “In any case, negotiations must resume, and something akin to the nuclear deal must be created. Otherwise, the problem will never be resolved.”

According to sources, Iran has hardened its stance. The govenment’s attitude can be described as, “If the military attack occurred because Iran refused to accept demands during negotiations with the United States, why should we negotiate again?”

Murakami sums it up: “So far, neither the United States, nor Israel, nor Iran has a next option. It’s close to a stalemate.”

This is the current state of the region after the 12-day war with no victors.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Kenji Nakanishi

Kenji Nakanishi is a deputy editor in the City News Department of the Yomiuri Shimbun Osaka.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

China Criticizes Sanae Takaichi, but China Itself Is to Blame for Worsening Relations with Japan

-

Withdrawal from International Organizations: U.S. Makes High-handed Move that Undermines Multilateral Cooperation

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Defense Spending Set to Top ¥9 Trillion: Vigilant Monitoring of Western Pacific Is Needed

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation