New ‘Families’ Find Support in Communal Living Beyond Bloodlines, Look for Other Ways to Bond as Household Size Decreases

The Hibarigaoka housing complex in Tokyo, captured from a Yomiuri helicopter in 1968, is considered the pioneer of large-scale housing complexes, accommodating many nuclear families who moved in during a period of high economic growth.

16:51 JST, November 4, 2025

Japanese lives have undergone dramatic changes in the 80 years since the end of World War II and the almost 100 years since the beginning of the Showa era (1926-89).The Yomiuri Shimbun explores the front lines of “family,” which is directly connected to our daily lives.

Just after 6 p.m. in August, the word “itadakimasu” (let’s eat) echoed in the air. A young boy and several elderly women gathered around a dinner table, smiling at each other and saying, “This is delicious, isn’t it?”

Although they look like grandparents and a grandchild, they are not related by blood. They are residents of Mitaka Tasedai no Ie (house of multiple generations), a shared house in Mitaka, Tokyo. In addition to having 15 rooms for residential nursing care facilities, it also functions as rental housing for single-parent families and students.

A meal provided at Mitaka Tasedai no le in Mitaka, Tokyo

Since residents began moving in at the end of May, 12 households with members aged 5 to 95 have made their home there. They share dinners in a familial atmosphere, building a family-like bond under one roof.

A working single mother raising her kindergarten-aged son decided to move in, wanting to live “in a place where my child can be looked after by many adults.” She and her son now have the opportunity to regularly eat with many people. “I was looking for a place where we could become as close as a family,” she said. “It is reassuring to have other adults around, and my son seems to be enjoying himself.”

Sitting across from the mother was a 91-year-old woman who used to live alone in the city. Nowadays, she smiles as she plays the card game karuta and tosses beanbags with the child after meals. “It gives me something to look forward to in life,” she said.

Dr. Kenichiro Murano, who founded the house, envisages it becoming a home where people of all ages can live together and support each other. “Interacting with children gives the elderly a purpose in life, and single-parent households can get support and avoid isolation,” he said.

Social isolation

In prewar and postwar Japan, family members handled the necessary chores and childcare in three-generation families, as well as in the subsequent nuclear families of couple and children.

However, due to the declining birth rate and aging population, the number of one-person and couples-only households has increased. The average household size decreased to 2.2 people in 2024, weakening the ability of family members to support one another.

According to the national census, the number of people aged 65 and older living alone increased from 3 million in 2000 to 6.7 million in 2020. This equates to around one in five elderly individuals.

The proportion of single-parent households to households with children remains high, making these households more susceptible to social isolation.

As the capacity for a single family to provide support reaches its limits, there is a growing trend toward communal living among people who are not related by blood but who mutually assist one another.

“In recent years, multigenerational share houses have been increasing as a form of living together and supporting each other,” said Ryoko Fukuzawa, a researcher at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute Inc.

Communal living

Since 2000, attempts at communal living have gradually garnered attention. Examples include “collective houses,” which are apartment buildings designed for multiple generations, and “intergenerational home shares,” where students live with and support the elderly.

Local governments are also focusing on home sharing. Since fiscal 2016, Kyoto Prefecture has been working on a project that provides students with vacant rooms in seniors’ homes at low rent.

By the end of fiscal 2024, it had supported a total of 70 coliving arrangements.

“The elderly can gain stimulation from young people and rely on them in times of need,” said a prefectural official. “In addition, young people can get to know the local culture and participate in the community.”

The Yamato Koriyama municipal government in Nara Prefecture also started a similar project in fiscal 2023.

“As the size of families shrinks, support based on loose connections will likely increase,” Fukuzawa said.

Reevaluate 3-generation families

Three-generation households were quite common before World War II. However, during the period of rapid economic growth and urbanization that began in the mid-1950s, more and more people moved from rural to urban areas, increasing the number of nuclear families.

According to the national census, nuclear families constituted the largest percentage of households in the country by 1960, at 38%. This percentage increased to 42% by 1980.

This photo, taken in 1976, shows a nuclear family consisting of a couple and three children.

During the period of rapid economic growth, it was common to get married, start a family and raise children. Gender roles were deeply rooted, with husbands working as breadwinners and wives working as full-time homemakers, responsible for housework and childcare.

Starting in the 1980s, the percentage of nuclear families began to decline. By contrast, the number of single-person households increased amid an increasing number of unmarried or late-marrying individuals along with a declining child population and an aging population.

The structure of the family became more dependent on individual choice due to increased participation of women in the workforce and the greater use of outside services for housework, childcare and eldercare, which had traditionally been done by the same family members.

An increasing number of people are choosing to live independently based on their own preferences, free from the traditional concept of family, such as remaining unmarried, choosing to divorce and women opting not to live with their husbands’ parents.

The percentage of single-person households exceeded 20% in the 1980s and reached a peak of 38% in the national census in 2020.

Prof. Masahiro Yamada, a family sociology specialist of Chuo University said, “single-person households are becoming the norm in Japan.”

Yamada says that when he asks students about their views on family, they often mention married couples living separately and choosing to spend time with like-minded friends instead of starting a family.

Improved internet access and more entertainment options have made remaining unmarried easier, encouraging people to prioritize their own lifestyles. “People are becoming more aware that they don’t have to force themselves to have a family,” Yamada said.

Male homemakers

Even in traditional nuclear families consisting of a married couple and their children, changing roles between husbands and wives has led to cases in which the husband becomes a full-time homemaker.

A 37-year-old man in Tokyo is a stay-at-home dad responsible for housework and raising his six-year-old son, who is in the first grade of elementary school. His 39-year-old wife works for a major non-life insurance company.

The man used to work in Gunma Prefecture and moved to Tokyo upon getting married in 2018. Not long after, his wife became pregnant.

He said: “I thought that it would be wasteful for my wife to sacrifice her career for childcare and housework. I also thought things would run more smoothly if I took on the responsibility, and I made the decision for the whole family.”

He also said: “Both my parents worked, so I did housework as a child. I don’t hold the view that men are meant for work.”

His remarks suggest that although family unity and connection are always valued, the concept of fatherhood is changing.

According to Associate Prof. Yuichiro Sakai, a family sociology specialist at Keio University, the perception of family has also changed in Western countries, broadening the definition of family.

For instance, families are now defined as special entities whose members provide mutual care, such as single mothers living together.

Sakai said: “In Japan, the number of single-person households is also increasing. It is difficult for members of the same family to help each other sufficiently. We need diverse forms of families that depart from the traditional stereotype.”

Support for living together

Amid this diversification, three-generation households, once common, are being reevaluated as a way for families to share responsibilities for caring for elderly people, preventing social isolation and providing childcare, among other family roles.

Some local governments are implementing support programs for three-generation households.

For example, Tonami in Toyama Prefecture launched a project in fiscal 2015 to support the construction and renovation of houses for family members to live together or nearby. The city had received more than 500 applications by fiscal 2024.

“Public interest in three-generation households is growing again as our project facilitates mutual support across generations,” a city official said.

Struggling between traditional family values and increasing diversity and options, people continue to explore ways that suit their individual circumstances.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

‘World’s Oldest Bio-Business’ Is Japan’s Seed Koji Retailing, Mold Used to Make Fermented Products like Sake, Miso, Soy Sauce

-

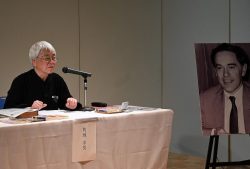

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts