‘Wind Phones’ Spread Globally as Tools to Cope with Grief; Disconnected Public Telephone Booths Let People ‘Talk’ to Lost Loved Ones

Itaru Sasaki stands beside the original “Kaze no Denwa” wind phone booth in Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture.

6:00 JST, July 20, 2025

MORIOKA — Telephone booths modeled after the “Kaze no Denwa” (Wind phone) in Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture — a public phone not connected to any network, set up as a place for people who lost loved ones in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake to say the things they wish they could tell the deceased — have begun popping up around the world.

Currently, there are wind phone booths in more than 400 locations across a total of 17 countries, including the United States, Germany and South Africa. They have reportedly been used by people who have lost loved ones to crises such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The first wind phone booth was set up in Otsuchi in December 2010. The booth contains a rotary telephone with no network connection. It got its name from the sound of wind blowing around the booth, which was seen as symbolic of what users might hear.

In 2014, a Japanese publishing company, Kinnohoshi Co., published a picture book titled “Kaze no Denwa” which depicted the original wind phone booth. A movie was also made in which the booth was centrally featured.

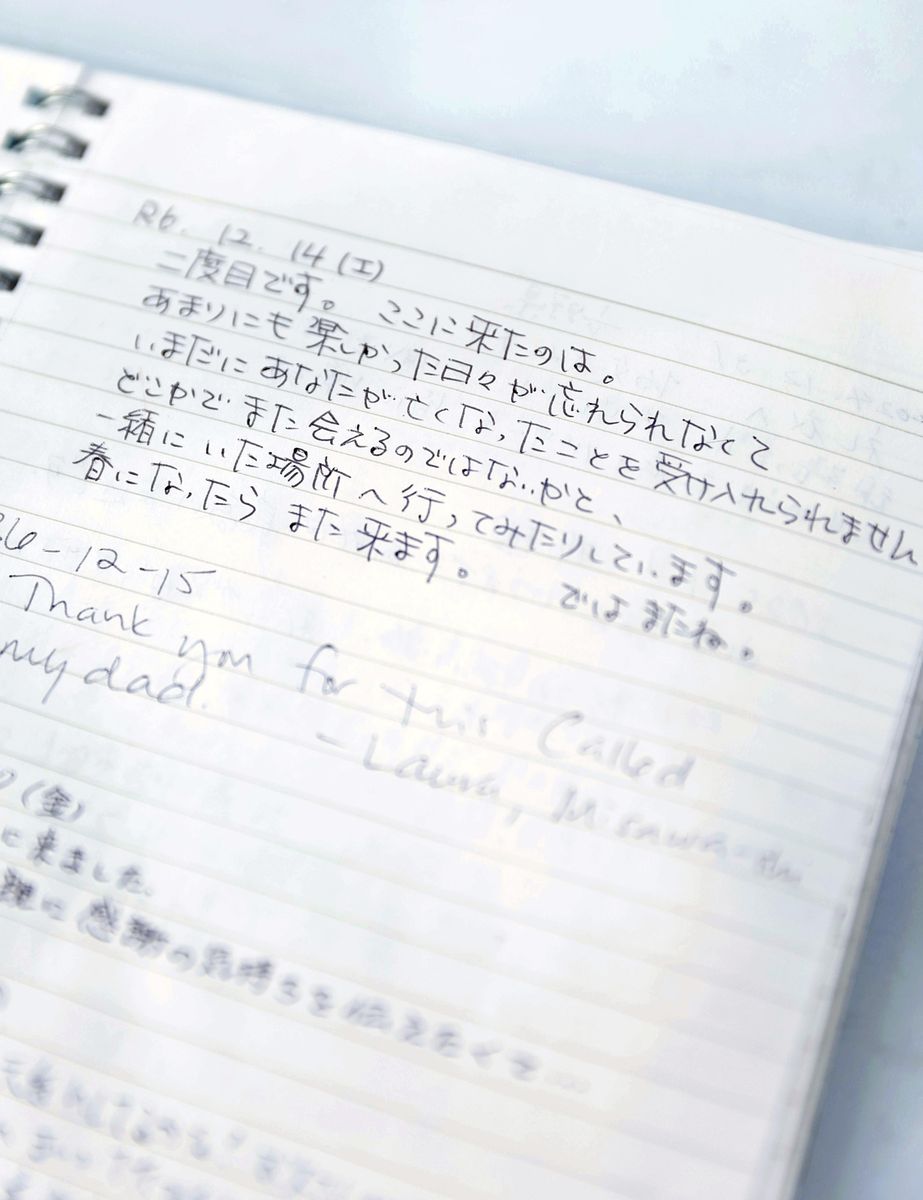

Messages left in a notebook by visitors to the wind phone booth

The wind phones have attracted attention also of experts overseas as tools for coping with grief.

In an area of Warsaw where foreign embassies are concentrated, there stands a glass-walled booth with a sign board informing people that it is a wind phone.

The booth contains a push-button telephone which is not connected to a network. It was set up in May 2022, and about 4,000 people have used it each year since then.

Katarzyna Boni, 43, a writer and resident of Warsaw, set up the wind phone booth based on her experience documenting conditions in coastal areas of Iwate Prefecture after the 2011 disaster.

She said, “The original idea was to help people going through loss during COVID pandemic. This kind of loss was quite similar to what happened in Japan on 3.11, when you couldn’t say goodbye. I thought we needed a place or environment to help with people’s sorrow that had nowhere to go.”

The booth also contains a notebook in which visitors may write whatever they like. The writings include messages to deceased friends or separated family members. One reads, “I love you,” and another, “I will keep on living tomorrow.”

She said that since the start of the war in Ukraine, an increasing number of evacuees from that country have used the wind phone booth.

The Otsuchi wind phone booth was set up about 15 years ago by Itaru Sasaki, 80. After his cousin died of an illness, he gave a lot of thought to telephones as a symbol of how people’s hearts can be connected beyond physical distance.

He received the public phone booth from a store that had shut down and placed it in the garden of his home. After the 2011 disaster, he started letting family members of disaster victims use the telephone booth, and many people from all over the nation began coming there.

In 2020, a movie titled “Kaze no Denwa” (“Voices in the Wind”), directed by Nobuhiro Suwa, received an honorable mention at the Berlin International Film Festival. The film depicts a girl trying to recover from her grief after losing family in the tsunami following the 2011 earthquake. This honor led to the wind phone booth becoming more widely known overseas.

Now, Sasaki said, people from many different countries visit his garden. He said, “In every era and country, there are many people who believe they can communicate with the deceased.”

Amy Dawson, 59, from the U.S. state of New Jersey, operates a website called My Wind Phone, which lists wind phone booths across the globe.

She said that as of July 11, there are wind phone booths in a total of 424 locations worldwide, excluding South America, and 300 of them are in the United States.

Five years ago, Dawson lost her second daughter, Emily, then 25, who passed away after battling an illness.

But she said, “There’s some comfort in dialing the person that you love, in dialing their phone number, in my case my daughter Emily. It’s such a normal and ordinary task in everyday life.”

Prof. Heather Servaty-Seib of Purdue University in the United States, an expert on psychology, said, “It’s an additional example of how grieving individuals find a way to be engaged, to remain connected with those who have died, or even with others who are going through some kind of loss. I think it is an interesting approach … It had really become a global phenomenon, and along the way there is some recognition and acknowledgement of the desire to stay connected, that ‘I’m not the only one who wants this opportunity.’”

Related Tags

Top Articles in Society

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

Record-Breaking Snow Cripples Public Transport in Hokkaido; 7,000 People Stay Overnight at New Chitose Airport

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Train Services in Tokyo Resume Following Power Outage That Suspended Yamanote, Keihin-Tohoku Lines (Update 4)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time