Tokyo’s Literary Bars: A Place Famous Writers Grabbed Drinks, Gained Inspiration; Many Artists Still Gather to Discuss Their Crafts

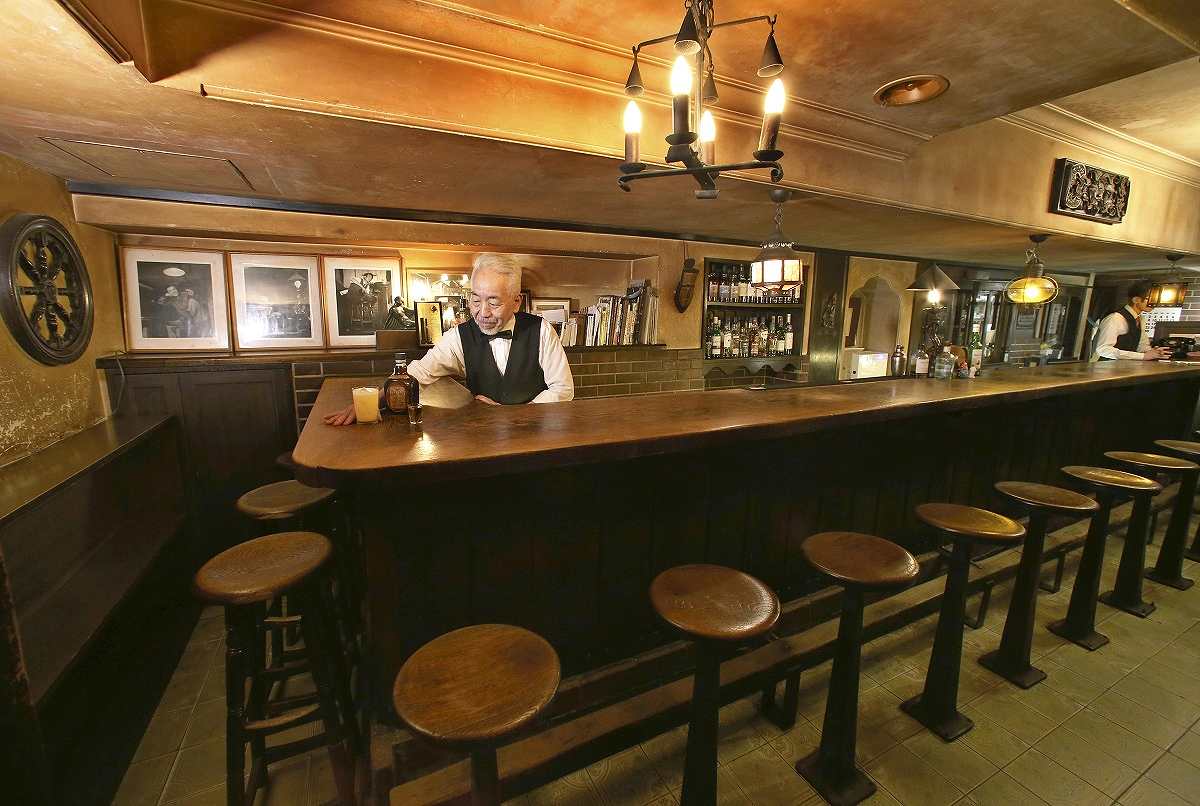

The interior of Lupin is seen on April 27. The seat at the left side of the bar counter is where Osamu Dazai sat in the past.

17:20 JST, June 24, 2024

The entrance of the bar Lupin in the Ginza district of Tokyo

Just off a busy high-end shopping street and down a dimly lit alleyway in the Ginza district of Tokyo, I saw a sign with an image of a famous fictional thief in a silk hat.

The sign was for the bar Lupin.

Founded in 1928, the bar attracted many famous Showa era (1926-89) authors such as Ango Sakaguchi as regulars. Opening the door and heading toward the basement led me to the bar with its wooden counter, which transports drinkers to a bygone era.

“This is the Golden Fizz,” said Ikuo Hiraki, 73, the bartender at Lupin, as he poured me a cocktail. “I heard that my predecessor served it to Mr. Ango when he seemed to be feeling down. He drank a lot of it.”

Hiraki, who has been a bartender at Lupin for a quarter of a century, poured the cocktail into a glass which was from the time Sakaguchi frequented the bar.

The smooth, sweet flavor of the Golden Fizz comes from mixing gin fizz and egg yolk. The drink must have given some comfort to the dispirited writer, who is now known as one of the Buraiha, or the decadent antiauthoritarian school of writers.

Helping artists

In the early Showa era in Ginza, there were many eating and drinking establishments known as “cafes” in which female employees would sit and converse with customers while serving them.

Lupin was founded by Yukiko Takasaki, who had worked at one such cafe called Tiger. Takasaki opened Lupin with the support of her regular customers, including Kan Kikuchi and Kyoka Izumi. Takasaki died in 1995.

Dazai loved sitting at the bar at Lupin. The photo of Dazai was taken by Tadahiko Hayashi.

In addition to Sakaguchi, Sakunosuke Oda and Osamu Dazai also often visited the bar. A famous photo of a drunken Dazai sitting on a bar stool with his legs on the stool next to him was taken at the bar and still hangs on the wall.

Akiyuki Nosaka, who was referred to as “the last regular” of the bar among the Showa literary world, wrote a novel which featured the bar and a proprietress resembling Takasaki. When a bar is frequented by writers, sometimes it produces its own work.

Naohiko Takasaki, 52, the grandson of the founder, said: “These days, women and foreign tourists don’t hesitate to come into the bar and sit at the counter alone, but in the past, only male customers, such as painters, writers and photographers would come in. It used to be a man’s world.”

“Unlike today, communication technology wasn’t very well developed,” he added. “Newspapers and publishing companies were located nearby, so people used to come here as a meeting place. If you came here, you could meet someone. I think bars were like a hub to meet intellectuals.”

Soaked in history

Many of the bars that were frequented by writers and editors during the Showa era were located in and around Ginza and Shinjuku. The battle over customers between the bar proprietresses of Osome and Espoir was depicted in Kawaguchi Matsutaro’s novel “Yoru no Cho” (Night butterflies). The work was also made into a movie.

However, in recent years, many of the bars have gone out of business.

For her book “Seiko,” writer Mayumi Mori interviewed the proprietress of Fumon, a bar in Shinjuku where writers, including Kazuo Dan and Masuji Ibuse, gathered. The bar closed in 2018.

“In the final days before [Fumon] closed, fans of Dazai came to the bar to talk to people who knew him and get a whiff of him. Today, people tend to deodorize things, but literary bars kept the scents of those who were no longer around, which had been lost elsewhere,” Mori said nostalgically.

Critics and writers would meet and hold discussions at Fumon.

In the afterword of her book, Mori writes that the bar was not just a convenient place for publishers to entertain writers, but also a nexus for cultural activities and ideological movements.

“It was not a place where female employees served writers,” Mori said. “It was more of a cultural intermediary.”

Cultural magnet

Literary bars still attract artists from various fields.

The bar Kazahana, which opened in 1980 and took the first kanji character in its name from Fumon, had been a venue for writers’ reading events before the bar moved to the Yotsuya district of Tokyo this year due to the age of its previous building in Shinjuku.

At first, the bar was considering shutting down, but after the regulars kept asking Kazahana not to close, it ended up moving to its current location.

The bar counter was moved from Shinjuku to Yotsuya, and the whiskey that late writer Kenji Nakagami loved to drink is still proudly displayed at the bar.

The bar’s owner, Kikuko Takizawa, said that playwrights would sometimes get into physical fights while writers would discuss literature until the sun came up.

Writers who are regulars get together to celebrate on the night Kazahana reopened after its relocation to the Yotsuya district of Tokyo.

“I didn’t set out to make a literary bar. I don’t know when people started calling it that,” Takizawa said. “It just naturally started attracting all kinds of strange people.”

No matter how convenient life becomes thanks to technology, there are some things you can only learn from speaking to people in person at bars and cafes. Literary bars are the unsung storytellers of literary history, and night after night, there will always be someone coming in for a drink.

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Record-Breaking Snow Cripples Public Transport in Hokkaido; 7,000 People Stay Overnight at New Chitose Airport

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture