Japanese Man Searches for Father’s Remains at WWII Site on Tinian Island, Amid Push to Bring Home War Dead

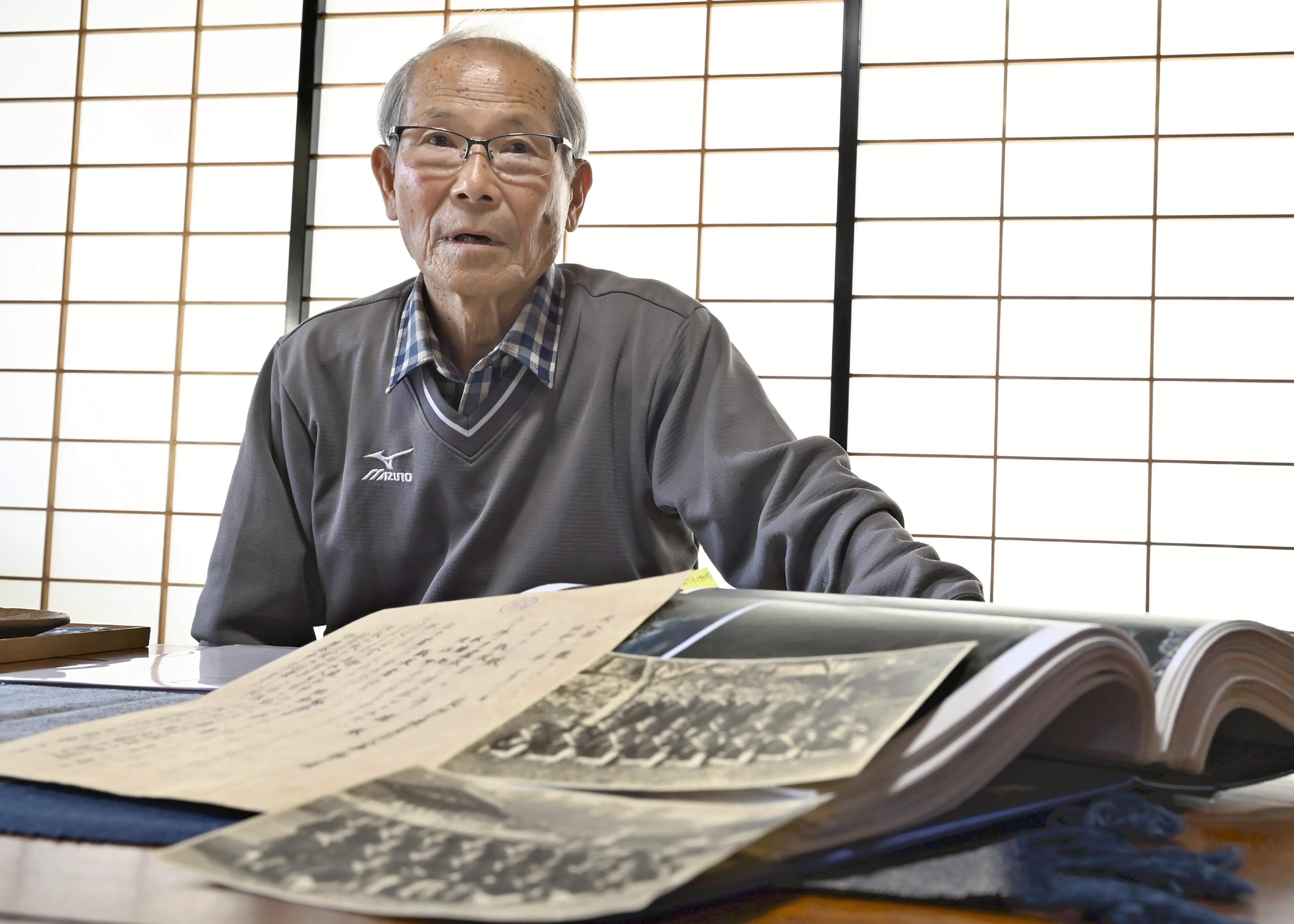

Isao Yamazaki speaks about his father, who died in battle on Tinian, on Dec. 22 in Izumo, Shimane Prefecture.

21:00 JST, January 9, 2026

Isao Yamazaki is still searching for the remains of his father and his father’s comrades, who died in battle during World War II on Tinian, a small island in the Northern Marianas.

Kinzaburo Yamazaki, who died in battle on Tinian

“I want to bring back to Japan as many remains buried there as possible,” Yamazaki said.

Tinian, roughly the size of Izu Oshima Island in Tokyo, became a Japanese territory after World War I. In July 1944, U.S. forces landed on the island. Japanese mandated units from Nagano Prefecture and elsewhere resisted, but they were defeated. The next year, B-29 bombers took off from the island to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The remains of nearly 5,000 Japanese people still rest on Tinian, and a mass burial site was recently discovered there. Yamazaki, 83, helped to try to identify burial sites on the island in April and May.

“There was an area with a slight rise to it, and when we dug down about 1.5 meters, the soil quality changed. We found human remains there. Right next to them, we found more remains, and we were certain it was a mass grave,” he recalled.

The discovery traces back to fiscal 2011, when the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry obtained from the U.S. National Archives a list of mass burial sites that had been compiled by the U.S. military.

The list indicates two mass graves on the island, as well as their respective latitudes and longitudes, and notes how many individuals were interred. A map was also found in fiscal 2014. However, no remains were discovered at the recorded locations.

A new lead came in fiscal 2023. Photos of wartime graves found by the ministry at the National WWII Museum in the United States showed distinctive stone steps. These steps were located during the survey in spring 2025, and excavation revealed human remains.

Yamazaki was at the site from July to August 2025. Remains, some still in shoes or with buttons near the chest, were uncovered one after another. Yamazaki witnessed those hints of life from 80 years ago.

“It felt like the remains were crying out in sorrow, and it nearly made me cry,” he said.

Yamazaki’s father Kinzaburo, who died at age 35, belonged to the Imperial Japanese Navy’s security force. According to a book by a Navy member who survived the war, the force was stationed along the coast and also near the burial site that was recently discovered.

Tinian was considered a vital part of Japan’s “Absolute National Defense Sphere,” essential to protecting the main islands and continuing the war, along with Saipan and Guam, which are also in the Northern Mariana Islands. Kinzaburo is believed to have died in July 1944. His remains have not been returned to his family.

When Kinzaburo was drafted, Yamazaki was less than a year old, and he does not remember his father. He was told by relatives and his mother Masuko, who died in 1992 at age 79, that his father worked in a lumber mill and was good at sports. But his mother wouldn’t talk much about his father.

“Since he was in the navy, he must have died on a sinking ship,” Yamazaki thought when he was younger.

After the war, he lived with his mother, who was sickly, and his older brother. Though money was tight, he studied hard, became a technical officer at the National Institute of Technology Matsue College and worked there until retirement.

One day after retirement, he looked again at his father’s official death notice. It said, “Killed in action while engaging enemy landing forces on Tinian Island.” His mother had barely managed to save the notice when her family home burned down around 1972. Yamazaki felt a growing desire to connect with his father.

In 2004, he visited Tinian for the first time as part of a memorial trip for bereaved families. The blazing sun and the blue sea left a strong impression. He remembered tears welling in his eyes as he wondered, “Did my father see this same landscape?”

He helped to collect remains and visited the site over ten times. Inside caves, he found hand grenades scattered about and a fork engraved with the name “Ono.” His heart ached as he thought, “What must those soldiers have felt in their final moments?”

He has submitted a sample of his own DNA to help identify his father. He also wants to search for the remains of his father’s comrades. “For us bereaved families, the war is not over,” he said. Eighty-one years after the war’s close, Yamazaki is set to head to the island once more.

Of the 3.1 million Japanese people who died in the war, 2.4 million lost their lives overseas, a category that includes Okinawa and Iwoto Island, formerly known as Iwo Jima. It is estimated that the remains of 1.12 million people have yet to be repatriated. The government is pushing to collect as many remains as possible by fiscal 2029.

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Record-Breaking Snow Cripples Public Transport in Hokkaido; 7,000 People Stay Overnight at New Chitose Airport

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease