Hikers relax at the summit of Mt. Oyama in Isehara, Kanagawa Prefecture.

11:00 JST, December 23, 2025

Oyama Afuri Shrine’s Shimosha (lower shrine)

Less than two hours from Tokyo, Mt. Oyama emerges from the forests of central Kanagawa Prefecture, offering tourists historic sites and spiritual experiences amid an abundance of nature.

With an elevation of 1,252 meters, the mountain is part of the scenic Tanzawa-Oyama Quasi-National Park. The area boasts gorges and waterfalls of varying sizes, along with primeval forests of beech and fir. In autumn, the foliage adds a palette of fall colors to the area.

Located on the mountain is Oyama Afuri Shrine, which is believed to have a history of more than 2,200 years. Several buildings make up the shrine, and its main facility, called Shimosha, or lower shrine, is at an elevation of about 700 meters, halfway up the mountain.

A view from Sekison cafe on Mt. Oyama

On clear days in autumn and winter, visitors can see far into the distance, all the way to Enoshima and Yokohama, two popular travel destinations in the prefecture that are dozens of kilometers away from the Shimosha. At a cafe called “Sekison” within the shrine grounds, visitors can soak up the view with a coffee and sweets.

While the mountain is a tourist destination centered on nature and hiking, it is also a historic site of pilgrimage.

The summit of Mt. Oyama, where Oyama Afuri Shrine’s main shrine is located, is frequently shrouded in clouds and mist, leading the mountain to be called “Amefuri yama,” or rainfall mountain. The mountain was deeply revered as a sacred site to offer prayers for rain and bountiful harvests.

The path leading to the summit of Mt. Oyama

The shrine was also a sacred site where warriors once offered prayers for lasting military success. It has been said that Minamoto no Yoritomo, the founder of the Kamakura shogunate, dedicated his sword to the shrine when he raised an army to fight against the Taira clan in the 12th century.

Later, Yoritomo’s act became a widely known folktale, and ordinary people flocked to the shrine to dedicate their own wooden swords. During the Edo period (1603-1867), it is believed that annually about 200,000 people made the pilgrimage to the mountain from Edo (currently Tokyo), which at that time had a population of about 1 million.

To accommodate the pilgrims, many shukubo inns — traditional lodging facilities where pilgrims stay while traveling to sacred sites — were established around the mountain. The area still has these inns. Their proprietors organize pilgrimages, perform purification rites for pilgrims and guide worshippers in religious practices.

Oosumi Sanso is one of the mountain’s shukubo. The current building was constructed in 1856.

During the Edo period, groups of skilled laborers, including traditional steeplejacks and firefighters, formed communal pilgrimage associations, called Oyama-ko, dedicated to visiting Mt. Oyama.

Oosumi Sanso still accommodates Oyama-ko pilgrimages, with some groups having as many as 67 pilgrims. There is a worship hall inside the shukubo, with a sacred mirror placed at the center of an altar. Signs bearing the names of some of the pilgrim associations are affixed to ceilings and walls throughout the building, and items such as braziers donated by the groups are also displayed.

Jun Sato, the 38th-generation proprietor of Oosumi Sanso, stands at the shukubo’s worship hall.

“People who visited our shukubo when I was little still come to this day,” said Jun Sato, the 38th-generation proprietor of the inn. “The tradition has been passed down through generations and I want to continue preserving it.”

Another shukubo called Tougakubou accepts general travelers, including families. According to Masato Aihara, who runs the inn, about 10% of its guests are foreign tourists from various countries and regions in Europe and Asia. The shukubo staff may not speak English fluently, but they assist their guests using translation apps on their smartphones.

At Tougakubou, guests can try spiritual experiences such as shakyo, a traditional Japanese practice and form of meditation in which people trace or rewrite sacred Buddhist sutras by hand. The practice is available for people of all faiths. Even if you don’t understand the meaning of the words, the process of slowly and mindfully writing them down helps with relaxation and focus.

Explaining traditional culture to foreign visitors is difficult, but new technology is proving effective. “There was a Russian guest who asked about the meaning of shakyo, so I used generative AI to explain it,” Aihara said.

The rotenburo open-air hot spring bath at Tougakubou

Tougakubou is also equipped with rotenburo open-air hot spring baths filled with water transported from a nearby facility.

Most Japanese public bath facilities refuse entry to people with tattoos. However, public baths at shukubo in Mt. Oyama have no such restrictions, as tattoos were quite popular among Edo period firefighters who formed Oyama-ko associations.

The Cultural Affairs Agency has been designating cultural properties and traditional cultures across Japan as “Japan Heritage,” aiming to revitalize local communities and promote tourism. Mt. Oyama and its surrounding areas have been designated as “Mt. Oyama Pilgrimage: The Commoners’ Journey of Faith and Leisure.”

Takako Oda of Nippon Travel Agency Co. visits Mt. Oyama frequently to develop travel products. “Despite being close to the capital, Mt. Oyama is relatively uncrowded, quiet and even mysterious,” she said. “The area holds significant potential as a destination for foreign visitors.”

Getting there

The nearest train station to Mt. Oyama is Isehara Station, which is about a one-hour train ride from Shinjuku Station in Tokyo on the Odakyu Line. It takes about 30 minutes by bus from Isehara Station to the trailhead for Mt. Oyama. The walk from the bus terminal to the Oyama cable car boarding area is about 15 minutes, and along the way tourists can stop at souvenir shops and restaurants, which line the street. One of the local specialties is a dish made with tofu produced using local water. It’s about a 6-minute ride by cable car to the station near the Shimosha.

The view from Shimosha is good, but climbing the mountain path for about 90 minutes from there will take you to the summit, where you can see even farther. There is also an area along the way where you can see a snowcapped Mt. Fuji. The trail has rocky, rugged sections that some people might find difficult to climb, so hiking boots are recommended, as well as plenty of water.

Related Tags

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

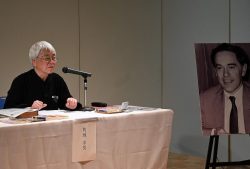

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

-

‘World’s Oldest Bio-Business’ Is Japan’s Seed Koji Retailing, Mold Used to Make Fermented Products like Sake, Miso, Soy Sauce

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed