Serhii and Svitlana with their 2-month-old son, Marko, in the Volyn region of Ukraine, on Oct. 3, 2023.

13:33 JST, October 15, 2023

KYIV – The two Russian Lancet drones hovered briefly over a small house-turned-military base in northeast Ukraine, then exploded. Inside, shrapnel pierced through the pelvis and thigh of a Ukrainian combat medic who goes by the call sign Alaska.

As the house burned and she was evacuated to safety, Alaska texted her boyfriend, who is in a different Ukrainian unit, using the military code for wounded: “I’m 300.”

That short message marked the start of a new chapter in their emotional – and physical – relationship, an experience now confronting many couples in Ukraine. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians have been severely wounded since Russia invaded in early 2022. Many soldiers return from the front in wheelchairs or needing prostheses. Often, the injuries – including amputations, facial damage and severe concussions – are life-altering.

Publicly, wounded soldiers are often hailed as heroes. In private, they must navigate the complicated ways their injuries have changed their bodies, minds and love lives.

“I was in constant pain, on medication, and was vomiting after my concussion, so I wasn’t happy to be next to anyone or happy to see anyone, including him,” Alaska, 30, said of her partner. It was weeks after she was wounded before he could leave his position to visit her and when he did, his presence did not always bring the joy she expected. “We had these moments when I wanted to break up,” she recalled. “The level of pain was so bad I even wanted to die by suicide.”

Olga Rudneva, CEO of Superhumans, a rehabilitation center in western Ukraine, said government data from July showed that 20,000 people – civilians and soldiers – had lost at least one limb since February 2022. The nature of the grinding artillery conflict means other injuries are also widespread, including burns and shrapnel and bullet wounds.

Alaska’s partner stuck with her, and after four months, they were intimate again for the first time since she was wounded. Almost a year later, she has redeployed to a position further from the front line because she is still in severe pain and relies on a cane to walk. A fellow soldier helped their relationship recovery by sharing a guide from Resex, an initiative from Veteran Hub, a Kyiv-based nonprofit that developed handbooks for soldiers on how to manage their sex lives after severe physical and emotional trauma, she said.

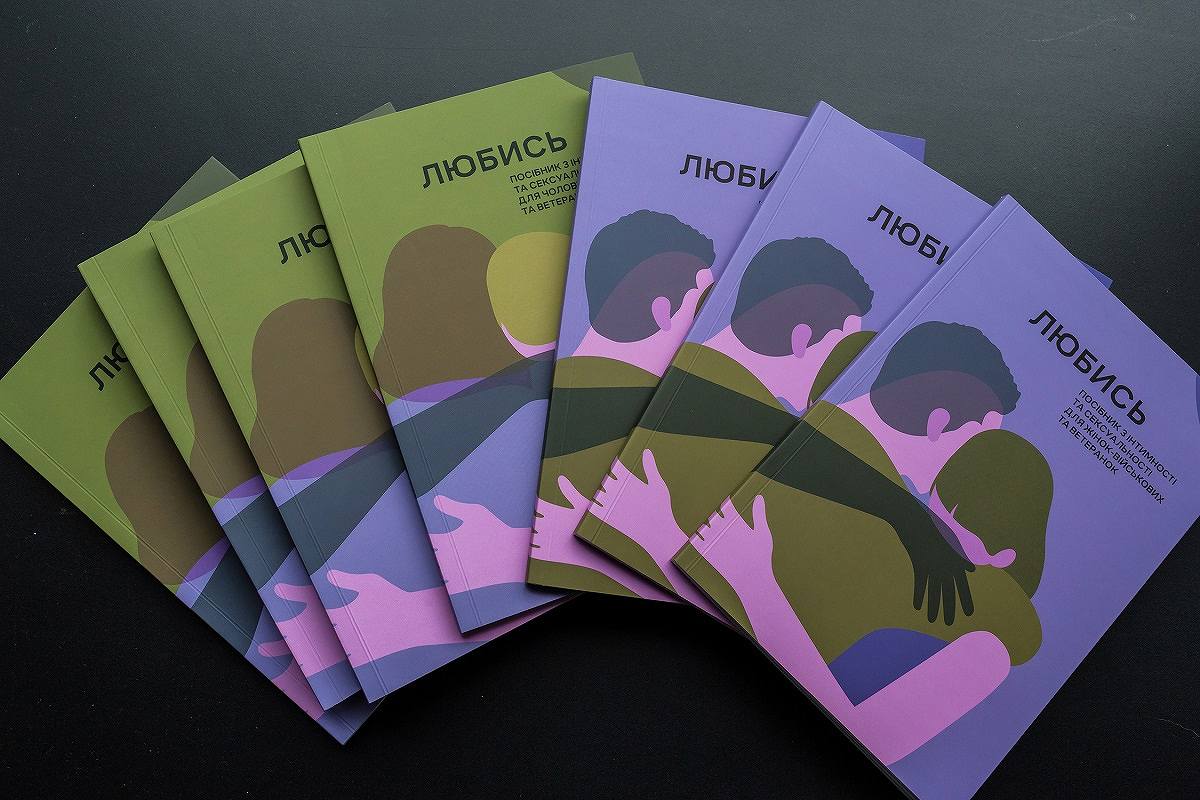

The Veteran Hub project Resex, a platform about sex life for wounded warriors, developed two manuals for male and female veterans. Each guide is based on the Veteran Hub team’s research on post-injury sexuality.

The books – with versions for men and women – use simple text and drawings to describe how sex organs work and how injuries might alter someone’s sexual experience. Medications like opioids may reduce libido, it warns, and for amputees, phantom pain might deter intimacy. “It can be painful from the very beginning because simple movement with amputation might cause severe pain and that leads to turn-off,” the book says.

The books suggest fostering closeness with partners through massages or by dancing and cooking together. If talking feels uncomfortable, it says, try writing a note to express “feelings and fantasies” and placing it somewhere your partner might find it, like in their bag or pocket.

Any wounds should be “healed properly” before engaging in sex, the handbooks advise. Otherwise, a partner could touch the wound by accident or behave too cautiously out of fear of causing pain.

Even so, many people decide not to wait.

After a long-range artillery attack struck his base last year, doctors gave Serhii Kopyshchyk a 20 percent chance of survival. Severe wounds to both legs required a double amputation. He was blinded in one eye, and shrapnel had ripped through his stomach and lungs.

But just weeks later, when his girlfriend, Svitlana, visited him, they had sex in the shower in his hospital room. “His belly was injured, he had no legs, but we’re a young couple,” she said with a laugh.

Yevhen Tiurin, 30, was single when a Russian soldier shot him in the leg during a gun battle in a wheat field in April 2022. The bullet first struck his calf, then ricocheted internally, lodging itself in his hip. By early May, doctors decided to amputate his right leg above his knee.

At the hospital where he was recovering in Lviv, a nurse caught his eye. “Prosthetics are really cool right now,” she told him. “You’re going to walk on two legs.”

From his hospital bed, a romance bloomed. They texted regularly. She visited him between shifts. Eventually, he proposed and – together – they learned what his body could and could not do. He felt some shame, he said, that when they were first dating, basic gestures – like carrying bags – that would have been a given before his injury were no longer possible.

He didn’t want his discomfort to affect their sex life. “When we started to make love I researched two or three positions I was sure I’d be able to do,” he said. As more time passes after an injury, he said, “the more you find positions that work for you.”

In August, their daughter, Mariya, was born. It helped, he said, that his wife is a nurse “who was next to me through the whole [recovery] process.”

Even in hospitals with other young, wounded soldiers, there was very little discussion of how their injuries would affect their sex lives, Tiurin said. Only one other soldier asked him for advice about sex positions, he said, but he wasn’t sure how helpful he could be: That man was also missing an arm.

There was no resource like Resex in 2015, when an enemy bullet ricocheted off Rodion Trystan’s rifle during a gunfight in eastern Ukraine, piercing his skull. He lost an eye and shrapnel damaged his brain and frontal skull bone. His heart briefly stopped but he was revived and fell into a coma.

With his missing eye and altered bone structure, he noticed how others treated him with respect when he was in uniform and alarm when in civilian clothes. “I was very nervous about my new face,” he said. When he tried dating again, some women admitted they were scared of his scars.

Rudneva, from Superhumans, said that in her experience, patients with facial injuries feel much more acute stress than those with limb amputations. Many “don’t leave their apartment because they are so scared of the way they look and so depressed by the fact they lost their identity,” she said.

With time and therapy, Trystan said, he learned to “accept rejection even when it’s rude.” Even when he became confident with his new appearance, he realized “it will not help in every case.”

“The game has changed, you have changed,” he said. “Don’t make a big deal about what other people think about you.”

But not everyone finds ways to adjust to their new reality.

Dmytro Pavlov, 31, a war veteran from Kramatorsk, Ukraine, was injured in his leg and doesn’t feel his left leg under the knee.

Dmytro Pavlov, 31, was a welding engineer in the eastern city of Kramatorsk before Russia attacked last February, spurring him to join his local territorial defense unit. Then, two days before his 30th birthday, he was shot in the back of the leg.

Single and having recently come out as gay to his unsupportive parents, he sunk into a deep loneliness in his hospital room hundreds of miles away in western Ukraine. Online, he sought support from the LGBTQ+ community and joined a Telegram channel for other gay troops, which helped him connect to his first sex partner after the injury.

But now, more than a year later and after seven surgeries, he still has no feeling in his foot. He struggles to walk and quit a job at a cafe because he couldn’t stay on his feet for the shifts, spurring fears he will not be able to pursue his longtime dream of becoming a pastry chef. He knows other wounded soldiers are successfully dating. But his romantic life is bleak, he said.

He tries to be upfront about his leg in his online dating profile, but when he mentions his war injury, he said “some people are just blocking me.” On the street, he said, “people look at me with this sorrow.”

Those who already have a supportive partner before being wounded often have a different experience.

For Kopyshchyk, who is now 25, it was a relief after losing both his legs and half his sight that he could still have intercourse. His relationship with Svitlana was new – based off a brief romance before the invasion and then hours of phone calls from his mortar position near Kherson. But the long calls – and then his injuries – bonded them, and the couple soon married.

When Svitlana learned she was pregnant, Kopyshchyk was determined to hold his child on two feet. He was treated at Superhumans, where he learned to walk on his prostheses just in time for his son’s birth.

Before his new legs, he said, sex was easiest for him from his wheelchair. Now, once Svitlana is recovered from birth, they will explore what role his legs might play in their sex life. “Even more will be possible,” he said.

On a recent morning, they sat on the edge of their bed, taking turns holding their son. She curled her toes around his prosthetic leg as they described how phone calls helped them stay connected to each other’s worlds when he was on the front line.

When he asked her over the phone just two weeks before he was wounded if she would be his girlfriend, he also asked: “Are you ready if something might happen to me?”

He still remembers her reply: “At least then you’ll have something to return to.”

And he did.

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

Trump Announces Trade Deal with Japan, Including 15% Tariff (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump to Put 25% Tariffs on Japan and South Korea, New Import Taxes on 12 Other Nations

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Soars to One-Year Peak on Trade Deal; Bonds Slide

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as Traders Lock in Gains after US Trade Deal Rally (UPDATE 1)

-

South Korea, Japan and US Conduct Air Drill as Defence Chiefs Meet

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Lawson to Offer Car Camping Service at Select Stores; 6 Chiba Stores to Offer Service from Monday

-

Japan Real Wages Fall for 5th Month in May

-

New Banknotes Account for Only 30% of All Bills in Circulation; Increased Use of Cashless Payments Seen as Cause of Slow Adoption Rate

-

Govt Mandates Collecting, Recycling of Some Devices with Lithium-Ion Batteries Amid Fire Concerns

-

Typhoon Nari Approaching Japan’s Kanto Region; Heavy Rain, Strong Wind Expected on Monday