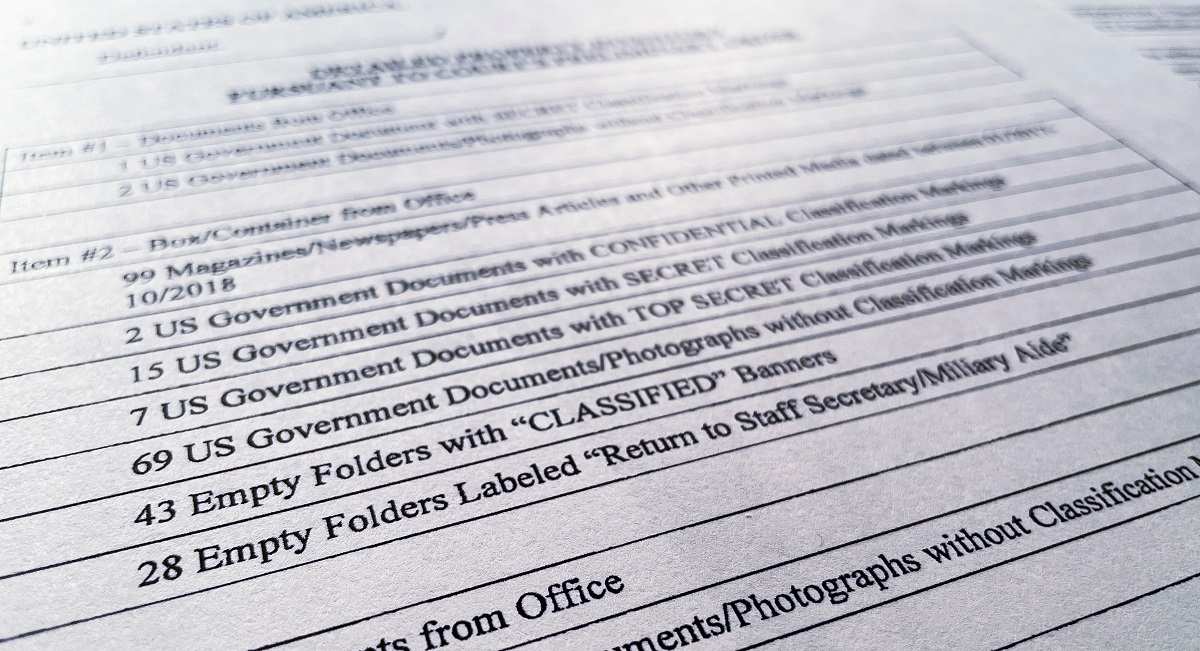

A detailed property inventory of documents and other items seized from former U.S. President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate shows the seizure of dozens of empty folders marked “Classified” or marked that they were to be returned to the president’s staff assistant or military aide after the inventory was released to the public by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida in West Palm Beach, Florida, U.S. September 2, 2022.

13:06 JST, July 30, 2023

Carlos De Oliveira, a middle-aged property manager from Florida, met with federal investigators in April for what is called a “queen for a day” session – a chance to set the record straight about prosecutors’ growing suspicions of his conduct at Donald Trump’s Florida home and private club. It did not go well, according to people familiar with the meeting.

De Oliveira, 56, knew Mar-a-Lago better than almost anyone. He’d worked there for more than a decade, and in January 2022 he was promoted to property manager, overseeing the estate. In the early years of De Oliveira’s employment, people familiar with the situation said, he’d impressed his boss by redoing ornate metalwork on doors at the property.

On Thursday, De Oliveira was indicted alongside Trump and his co-worker Waltine “Walt” Nauta – all three accused of seeking to delete security footage the Justice Department was requesting as part of its classified documents investigation.

De Oliveira is the third defendant in the first-ever federal criminal case against a former president. Trump, who was initially indicted with Nauta in June, is charged with mishandling dozens of classified documents in his post-presidency life and allegedly scheming with his two employees to cover up what he’d done.

This previously unreported account of De Oliveira’s actions at Mar-a-Lago, and later statements to federal investigators, shows how the longtime Trump employee has become a key figure in the investigation, one whose alleged actions could bolster the obstruction case against the former president. Most people interviewed spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private conversations or details of an ongoing criminal probe.

De Oliveira’s attorney, John Irving, declined to comment.

The series of discussions between De Oliveira and investigators highlight how prosecutors led by special counsel Jack Smith have approached Trump employees with a mixture of hope and suspicion: hope that the former president’s employees could explain what had happened inside Mar-a-Lago, and suspicion that whatever misdeeds may have occurred, they might have been aided by servants who stayed loyal to the boss – even after the FBI came knocking.

When FBI agents arrived at Mar-a-Lago the morning of Aug. 8 with a court-issued search warrant, De Oliveira was one of the first people they turned to. They asked him to unlock a storage room where boxes of documents were kept, people familiar with what happened said. De Oliveira said he wasn’t sure where the key was, because he’d given it to either the Secret Service agents guarding the former president or staffers for Trump’s post-presidency office, the people said.

Frustrated, the agents simply cut the lock on the gold-colored door. The incident became part of what investigators would see as a troubling pattern with the answers De Oliveira gave them as they investigated Trump, the people said. Current and former law enforcement officials said witnesses often mislead them, particularly early in investigations. But those bad answers get more dangerous as agents continue to gather information.

Investigators’ interest in De Oliveira started to rise when security camera footage from the mansion showed him helping Nauta move boxes back into the storage area more than two months earlier, on June 2, 2022, the people said. That was just a day before a federal prosecutor and agents visited Mar-a-Lago to recover classified documents in response to a grand jury subpoena and to look around the place.

The National Archives and Records Administration had launched an effort to retrieve all government documents still in Trump’s possession in 2021. The FBI and Justice Department got involved in early 2022, after archives officials found classified documents among 15 boxes of material that Trump had sent the agency.

When authorities entered the storage room that June day, Trump’s lawyers told them they could not look into the many boxes inside. Many of those boxes, security footage would later show, had been placed there the day before by Nauta and De Oliveira, according to the indictment.

Officials didn’t like the answer but accepted it, for the time being. Trump’s legal team also handed over a sealed envelope with 38 classified documents and tried to assure the federal officials that they had conducted a diligent search at Mar-a-Lago.

Agents had another concern: The lock on the door to the storage room was flimsy. The officials urged staff to put a better lock on the door, which De Oliveira did – using a hasp and a padlock to keep it secure, the people said. If there were still highly sensitive classified documents in the room, such a lock was far from sufficient, but it was better than nothing.

Footage from Mar-a-Lago would also show De Oliveira on June 3 as he loaded items, including at least one box, into an SUV to go to Bedminster, N.J., where Trump planned to spend much of the summer, according to the indictment.

Within weeks of the Justice Department visit in early June, the FBI had gathered evidence suggesting that Trump might not have turned over all the classified papers in his possession. Between June 22 and 24, government officials discussed with Trump’s attorney and then issued a subpoena for security camera footage to see if they could follow movements of people and material inside the complex. Of particular interest were cameras in a hallway that led from residential space toward the storage room, the people familiar with the situation said.

When the FBI returned with its warrant in August of last year, agents found 75 additional classified documents in the storage room and 27 more in Trump’s office, the indictment says.

On June 23, Trump had a 24-minute phone call with De Oliveira, the indictment says. Around the same time, De Oliveira and Nauta had text conversations with another Trump employee at the facility, whom people familiar with the investigation have identified as IT worker Yuscil Taveras.

Three days later, according to the indictment and people familiar with the investigation, De Oliveira pulled Taveras aside for a face-to-face conversation. De Oliveira wanted to know how long the camera system’s computer server stored the images it recorded, the people said.

According to a superseding indictment unsealed Thursday, De Oliveira told Taveras – identified as “Employee 4” in the court document – “that ‘the boss’ wanted the server deleted.”

The employee replied “that he would not know how to do that, and that he did not believe that he would have the rights to do that,” according to the indictment. “De Oliveira then insisted to Trump Employee 4 that ‘the boss’ wanted the server deleted and asked, ‘What are we going to do?'”

After the meeting, De Oliveira walked “through the bushes on the northern edge of the Mar-a-Lago Club property” to meet Nauta, walked back to Taveras’s IT office, then walked back to meet with Nauta again on the neighboring property, according to the indictment. The charging document does not spell out what prosecutors think the significance of those movements is, but they suggest that the two men were trying to have discussions out of sight of their co-workers.

The indictment does not allege that the footage was deleted, and authorities have said in court papers that the security camera footage they received provided critical evidence in their case.

Over that summer, it became clear that the feds weren’t going away, nor were their demands for security camera footage. Evidence gathered by investigators shows that Trump returned twice to the property in July, once from July 10 to 12, and again on July 23, the people said. Prosecutors eventually sought security footage covering that time period as well.

In January 2023, De Oliveira was questioned by investigators at his home, according to the indictment. His answers left agents more suspicious of him, the people familiar with the situation said.

Weeks later, agents seized his phone, the people said. He was subpoenaed to testify in April before the federal grand jury. By that point, it was clear that prosecutors were deeply skeptical of De Oliveira’s explanations of his interactions with Trump and Nauta, and his occasional claims of faulty memory.

For one thing, De Oliveira said he did not remember his boss coming back to Mar-a-Lago in July, the people said. Trump tended to stay away from the Florida summer heat, and it did not seem likely to some investigators that De Oliveira would forget the former president showing up twice in two weeks.

The prosecutors’ dissatisfaction came to a head in mid-April, when De Oliveira was given a proffer session – an interview in which a prosecutor and a defense lawyer meet with a person to decide if they have valuable information to offer an investigation, the kind that could lead to a plea deal.

Such meetings are often called “queen for a day” sessions because the person being questioned will not have their answers used against them, unless they lie.

After the session, people familiar with the matter said, prosecutors told De Oliveira’s lawyer that they believed he was not being truthful and should expect to be charged.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan