Progress on emissions, but not nearly enough

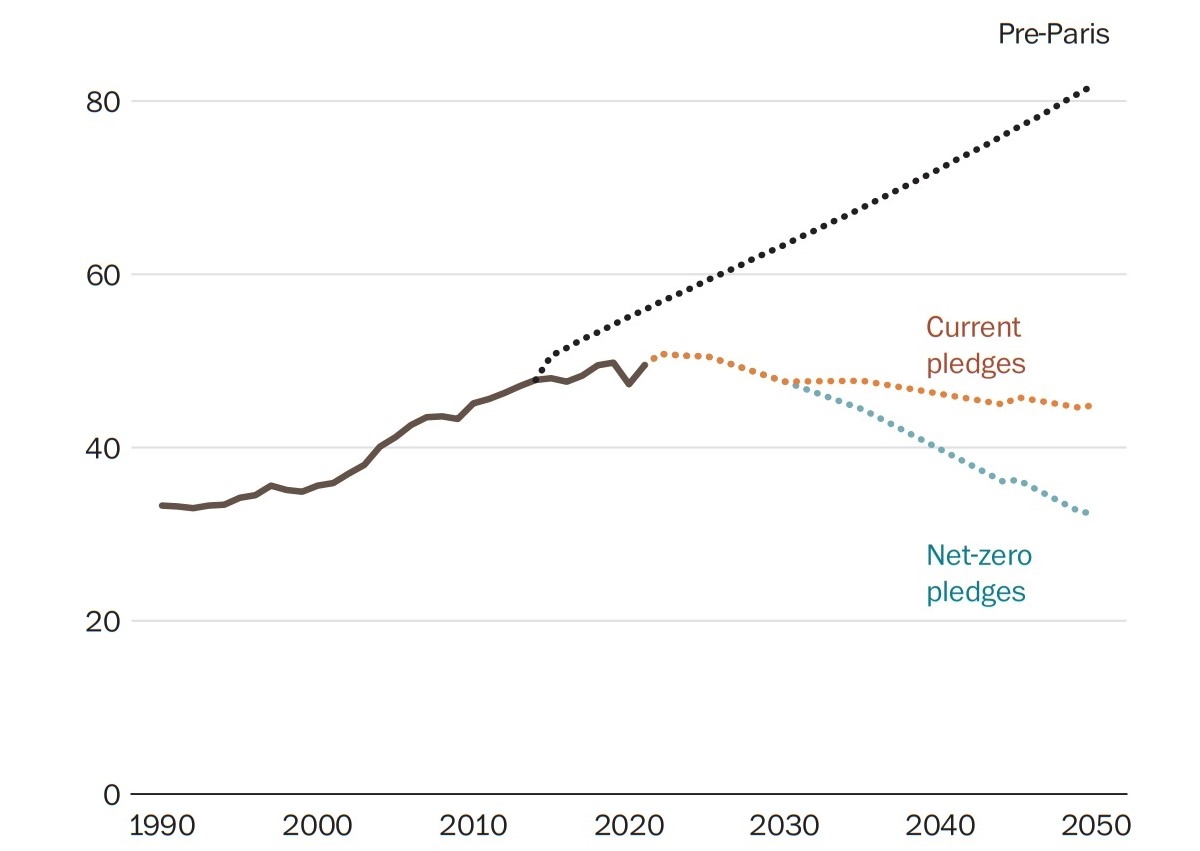

Greenhouse gas emissions, shown in billion tons, are on a much better course since the Paris agreement.

But they are set to continue at high levels for decades.

Data show emissions of all greenhouse gases in billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) and include emissions and removals from land use change and forestry.

Te efect of the Kigali Amendment is included in the “current pledges” line.

(Source: IEA WEO 2022, Rhodium Group)

16:54 JST, July 20, 2023

As parts of the Northern Hemisphere reach heat close to the limits of human survival, Chinese leader Xi Jinping declared in remarks reported Wednesday that Beijing alone will decide how – and how quickly – it addresses climate change.

Xi’s comments to top Communist Party officials, which came as U.S. climate envoy John F. Kerry wrapped up three days of talks with his Chinese counterpart, laid bare the challenge the world faces in curbing planet-warming pollution that is fueling heat waves across three continents. China has surpassed the United States as the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, and approved the construction of dozens of coal plants last year even as it added more renewable power.

China would pursue its commitments “unswervingly,” but the pace of such efforts “should and must be” determined without outside interference, Xi said late Tuesday. Xi’s approach marked a break from the 2015 Paris climate accord, where a Chinese-U.S. agreement paved the way for the international goal of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels.

The effect of heat-trapping gases has reverberated across the globe in recent weeks, as historic heat waves have enveloped China, southern Europe, the Middle East and North America and massive wildfires have incinerated forests from Canada to Greece. Rising average temperatures intensified by the El Niño climate pattern put 2023 well on course to be the hottest year since humanity started keeping track.

Speaking to reporters in a phone call Wednesday, Kerry described his talks with Chinese officials as “very cordial, very direct, and, I think, very productive,” but he acknowledged that they did not produce a significant breakthrough. The meetings marked the first time in a year that the two sides had met.

“We’re here to break new ground because we think that’s essential,” Kerry said. “But we had a very extensive set of frank conversations and realized it’s going to take a little bit more work to break the new ground.”

Kerry said the ongoing global heat wave has influenced the talks. “I think the intensity and sense of urgency has grown for everybody. If we don’t break new ground, it’s going to be even harder to be able to tame the monster that has been created in terms of the climate crisis. So we have our work cut out for us.”

Still, Beijing made it clear that domestic concerns would shape its approach to energy. China’s world-leading emissions totaled 11.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2022, according to the Global Carbon Project, a decline of less than 1 percent from 2021 levels.

Xi’s message – delivered at the same time Kerry was in town – was no coincidence, according to Li Shuo, a senior policy adviser for Greenpeace East Asia. Xi was showing that “China will decide its own path in achieving carbon goals and will not be ordered about by others,” he said.

Climate negotiations between the two countries, once a rare bright spot in a fraught relationship, have increasingly been undermined by tensions over trade, technology and human rights. Kerry spent a 12-hour day with his Chinese counterpart, Xie Zhenhua, on Monday. When he saw Vice Premier Han Zheng on Wednesday, Kerry called for climate to be a “free-standing” issue, kept separate from the broader bilateral acrimony.

But many Chinese experts framed the visit as being part of a tentative diplomatic reset, following trips by Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen, rather than a breakthrough in climate negotiations.

China has bristled at a shift in the Biden administration’s climate approach, in which talks are supplemented by more coercive measures to push China to move faster, like tariffs on high-emission steel and aluminum imports.

The United States was “ignoring China’s contributions and achievements in reducing emissions and blindly pressures China to make unrealistic commitments,” Chen Ying, a researcher at the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said in an interview with local media.

But it isn’t just pressure from the United States that is compelling China to act.

Flash floods, sudden cold snaps and other deadly extreme weather events in recent years have raised public awareness in China of the dangers of a warming atmosphere. The government has responded with promises to improve warning systems and disaster response mechanisms to protect livelihoods, the economy and even precious historical artifacts during future crises.

But people in China are feeling the extremes this summer. Temperatures in northern parts of the country have reached searing heights in recent weeks, even as torrential rainfall and typhoons batter its southeastern shores.

A record high of 52.2 degrees Celsius (126 Fahrenheit) was recorded Sunday in a small township in the Turpan Depression, a stretch of desert in the northwest that sinks as low as 150 meters below sea level. At the opposite end of the country, southeastern Guangxi province issued a red alert for flooding and landslides on Tuesday as Typhoon Talim made its way inland.

Chinese officials have focused on softening the impact of extreme weather, rather than cutting emissions, even if it means burning more fossil fuels.

After last summer’s – also record-breaking – heat wave dried up reservoirs and caused power shortages from idled hydropower stations, the government has turned to coal to ensure the same doesn’t happen this year. Local authorities approved more coal power plants in 2022 than in any year since 2015.

Ensuring power supply during peak summer demand affected the welfare of every family, another vice premier, Ding Xuexiang, told one of China’s largest power providers over the weekend.

To keep the air conditioning on, providers like CHN Energy, one of the world’s largest generators of coal-fired power, have been setting daily records for supply, the Global Times, a state-run newspaper, reported on Monday.

The extreme heat seen around the world right now still pales in comparison to what could happen even if we limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, said Bill Hare, the CEO of Climate Analytics, which analyzes the global emissions picture and its consequences.

“We’re at 1.2 degree warming, and we know that certain kinds of heat extremes could increase in intensity by another 30 to 40 percent,” Hare said. The picture only gets worse from there.

The world is still on a trajectory for rising temperatures since global emissions have arguably flattened in recent years, but have not yet shown any clear decline. This means that every year continues to further fill the “bathtub” that is one of experts’ favorite metaphors for the atmosphere as it continues to take on our pollution.

“We are not only not draining the tub, but we’re continuing to fill it, pretty much at the same pace as we have been,” said Kate Larsen, a partner at the Rhodium Group, a research firm that tracks and models global emissions.

“Barring any major fundamental changes, we’re just adding more emissions,” Larsen said. “And nothing on the horizon, whether it’s the U.S.-China agreement or the COP, really changes that.”

Countries’ current promises under the Paris agreement would push the Earth well past 2 degrees Celsius of warming, according to Rhodium data. Even current “net zero” pledges added on top of that only take the world back to 1990 levels of emissions by 2050, Larsen noted.

Limiting warming to just 1.5 degrees Celsius would require much sharper cuts. Emissions have declined in some parts of the world, like the United States and European Union, in recent years, but they continue to rise in others.

Lawmakers in Europe, hoping to take a break from the challenges of the war in Ukraine with the cherished tradition of the mid-July vacation, were met with the hellish temperatures of another heat wave that served as a scorching reminder that the climate crisis does not take a summer holiday. The latest heat wave there has already notched temperatures above 104 Fahrenheit (40 C) in parts of Spain, France, Italy and Greece. In Sicily, the temperature was as high as 115 degrees F.

Some of Brussels’s ambitious climate plans, however, are strongly opposed by conservatives in the European Union in a sign that the bloc remains split on how, exactly, to proceed. More than 61,000 people died in heat waves across Europe last year, according to a recent study published by Nature Medicine. A study in published in May projected that the chance of what were once rare heat waves in Europe will rise as the climate warms.

And in Canada, where wildfires have forced a record number of people from their homes, blanketed cities from coast to coast in a haze of toxic smoke and charred an unprecedented 27 million acres, it has not yet shifted the foundations of the climate debate in a nation that’s home to the world’s third-largest proven oil reserves.

In May, climate change was barely, if at all, mentioned during a provincial election in oil-rich Alberta, even as massive wildfires threatened oil and gas operations and prompted candidates to temporarily suspend their campaigns. After her election, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has continued to attack Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s climate policies, as has Trudeau’s main political rival, federal Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre.

Trudeau, who came to power in 2015 vowing more aggressive action on climate change, has also faced criticism for not moving fast enough to reduce emissions and for buying the TransMountain oil pipeline five years ago.

Kathryn Harrison, a political scientist at the University of British Columbia, predicted that this summer’s extreme weather “will surely have an impact on Canadians’ awareness of the urgency of climate change.”

But she said that “humans seem to have an amazing ability to return to business as usual after an emergency passes.” Two years ago, more than 600 people in British Columbia died during a heat dome, Harrison noted, but “it often feels like my fellow British Columbians just moved on.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan