Maurine Seto, a school librarian in California, designated a chess area in the library to accommodate student demand.

13:04 JST, April 16, 2023

Jeffrey Otterby, a middle school teacher in Illinois, is facing an epidemic of student distraction. When his seventh-graders are supposed to be learning social studies, they are glued to their school-issued Chromebooks. He has taken to standing in the back of the room to monitor their screens, where he can see the online game they’re all playing:

Chess.

“I guess I’m happier they are playing chess rather than some shoot-’em-up game. Actually, I love it,” said Otterby, a chess enthusiast. “I just need them to do it at a better time.”

Otterby’s crop of middle-schoolers in the St. Charles Community district are not alone. Across the country, students from second grade to senior year have stumbled across a new obsession, which is, in fact, a centuries-old game. Interviews with teachers and students in eight states paint a picture of captivated students squeezing games in wherever and whenever they can: at lunch, at recess and illicitly during lessons, a phenomenon that is at once bemusing, frustrating and delighting teachers.

Data from Chess.com, whose usership is the highest it’s ever been, and anecdotal evidence nationwide suggest a fervid, growing base of young users. This month’s National High School Chess Championship in D.C. had to add overflow rooms to accommodate a record 1,750 attendees – spurring fears of a shortage of participation medals.

A California school librarian this year set aside a portion of her library for chess-playing students to indulge their habit during lunchtime. An Illinois teacher bought 24 chess sets to meet surging student demand. And in Hawaii, passion for chess is messing up the morning routine.

“Before school, they’re supposed to line up and head upstairs in an orderly fashion,” said Kevin Nitta, a teacher at the private St. Patrick School in Honolulu. “But now it’s chaos, because they can’t see the stairs – because they’re all looking at Chess.com on their Chromebooks.”

It’s unclear what is driving the sudden adoration of chess among tweens and teens. Students and chess spectators point to the influence of chess stars and social media personalities such as Levy Rozman, whose YouTube channel GothamChess has more than 3.5 million subscribers; Hikaru Nakamura, an American grandmaster with 1.9 million YouTube subscribers; and the Botez sisters, elite American Canadian players who boast a combined following of close to 2 million on YouTube and Twitch.

Max Magidin, a 15-year-old attending California’s Burlingame High School, said chess content began showing up on his and his friends’ TikTok feeds early this year. Almost immediately, it seemed everyone in the Bay Area’s San Mateo Union High School District was playing the game – including Magidin, who nowadays fits in between two and four hours of chess daily. He plays with friends in the library at lunch, sneaks a few rounds of chess puzzles during class and plays after school for one to two hours in the window of free time he formerly devoted to video games.

“When a lot of people are talking about it and doing it, you also want to partake in that activity,” Magidin said. “And learning off YouTube and other social medias has been very entertaining.”

Chess has always been something of a faddish sport, said David Mehler, the president of the U.S. Chess Center. He recalled a big jump in interest in the early 1990s after the release of the movie “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” which tells the story of a 7-year-old chess prodigy and is based on the life of grandmaster Joshua Waitzkin.

More recently, chess experienced a spike in popularity among adults at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, and again when many people confined to their homes streamed “The Queen’s Gambit,” a Netflix series, said Erik Allebest, the chief executive and a founder of Chess.com. After the virus arrived, Chess.com’s average daily user count of 1.5 million rose to between 5 million and 7 million, he said.

In late December, the daily user count for Chess.com exploded again – hitting a record 10 million. The growth has continued: As of April, Chess.com is averaging 12 million users a day, Allebest said. Chess.com does not track users’ ages, Allebest said, but as best he and Chess.com staffers can tell, the latest wave of fandom is dominated by middle and high school students.

“We keep our finger on the pulse anecdotally throughout the broader social networks,” Allebest said. “There is a lot of content being created by kids in junior high and high school showing the amount of chess being played in their schools.”

He sent links to viral Reddit posts in which K-12 teachers lament an outbreak of chess enthusiasm and grade school students share tales of administrative crackdowns limiting access to Chess.com. (The Washington Post found no examples of the latter.) Allebest also noted that his own son, 15, has become a chess convert – not because of his father’s job but through watching GothamChess on YouTube.

Some teachers have mixed feelings about the clandestine playing of chess in their classes.

Justine Wewers, a high school geography teacher in Minnesota’s Anoka-Hennepin district, said she has seen a wearying number of student infatuations over the years, including video games, “Uno” and fidget spinners. By comparison, the chess craze strikes her as a healthy activity for young minds.

Still, she wishes her students would stop clicking to Chess.com on their Chromebooks and iPhones mid-lesson, as roughly one-third of her 150 ninth-graders at Blaine High School try to do each day, she estimates. She tries to be accommodating – “If they’re done with their work and trying to do a chess move real quick, I understand” – but she has to draw the line somewhere.

As punishment, she has begun taking children’s devices from them: “You have to physically take their phones and put them elsewhere, because if they’re seeing it on their desks, they’re just too tempted to play chess.”

James Brown, a teacher in New York’s South Colonie School District, sees nothing but positives.

Brown, who teaches computer science and programming at Sand Creek Middle School, has long set Fridays aside as a free period for children to pursue activities of their choice. Since January, many students have chosen chess, leading Brown to buy three more chess sets to augment the 10 he already owned.

He is thrilled to hear the click of rooks and queens moving across the boards. He believes chess helps students to develop critical thinking skills, strategic muscle and the ability to take calculated risks – a conviction borne out by decades of research suggesting that the game boosts children’s mathematical and cognitive capacities.

“It’s all things we want to instill in the student,” Brown said. “If they’re doing that on their own, in a format that is fun for them, it ties right into what I’m trying to do. I don’t see it as a distraction; I see it as a benefit.”

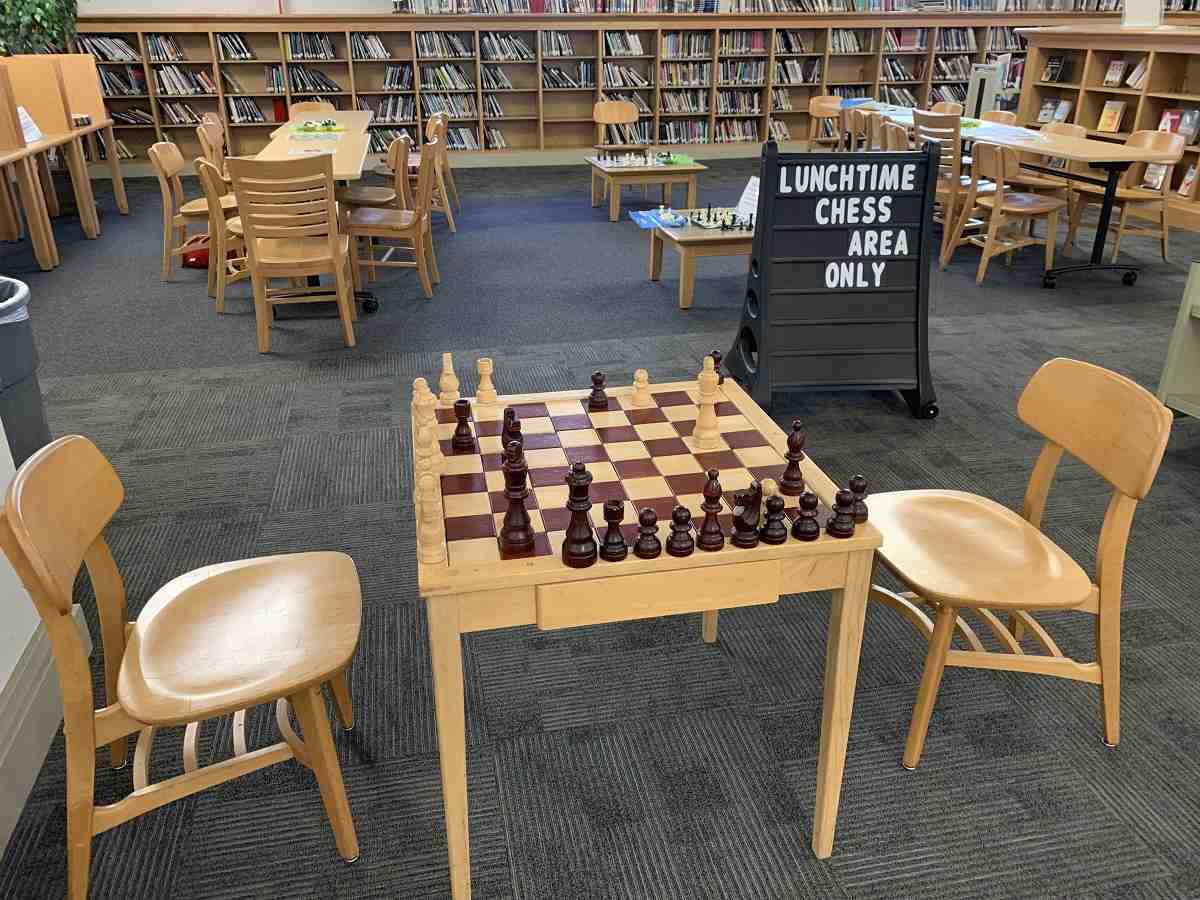

Another benefit of playing chess is its transcendence of social groups, said Maurine Seto, a librarian at California’s Burlingame High School. In early 2023, she said, students started stampeding into her library before school, during lunch and in snatches between classes to play chess at a handful of tables.

“It pairs different sets of kids together that you don’t normally see,” Seto said. “They come up and say, ‘Hey, do you wanna play chess?’ and I normally would never see those two kids interact.”

Noticing fights over the seats, Seto expanded the number of tables and chess boards to 10. She also added a sign warning, “Lunchtime Chess Area Only.” The crowd of student players is generally respectful, she said, although she must occasionally remind them not to use foul language in the heat of competition.

In some places, the mania for chess is inspiring the founding of formal chess clubs and tournaments.

At Illinois’ Shiloh Junior High School, social studies teacher Noah Allen recently obtained permission from the Shiloh CUSD 1 board to form a junior high chess team, which is to be launched next school year. In the meantime, he is deluged by student interest. Twenty children – a third of the 65-strong student body – regularly attend preliminary club meetings just to practice.

“Honestly,” Allen said, “it’s kind of odd.”

Spencer Noerrlinger, 13, right, started a chess club this year after noticing that many of his peers at his Nebraska school had become chess fans, too.

In Nebraska, 13-year-old Spencer Noerrlinger was ahead of the curve. Noerrlinger has been a chess aficionado for half his life: He discovered a love for the game at age 6, playing his father.

Sitting in study hall one foggy day this winter, Noerrlinger looked up and was astonished to see all of his Syracuse Middle School classmates sitting down, quiet. Normally, the teacher has to remind them to keep their seats, he said.

And it got weirder – everyone around Noerrlinger was on Chess.com, playing the seventh-grader’s favorite game. Struck by an idea, Noerrlinger crossed the room to his best buddy, Lucas.

“You know,” Noerrlinger recalled saying, “maybe we should start a chess club.”

A few days later, Noerrlinger pitched the idea to principal Tim Farley, who was an instant convert. Syracuse-Dunbar-Avoca Public Schools Superintendent David Kraus also approved, given that his own children had succumbed to chess fascination (his fifth-grade son Landry took a chess board to this year’s Easter celebrations and demanded that family members take turns playing him).

Every school morning since January, the Syracuse Chess Club, known by members as the SCC, has met in the gym bleachers between 7:45 and 8:15. Students fit in two, maybe three games before class, Noerrlinger said. The club has hosted one tournament, which drew 32 participants, and is hosting a second one, with 38 competitors.

Noerrlinger was knocked out in the first tournament, beaten by his biggest rival, Brock. But, he said, he’s hopeful about his chances this time around.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza