Heirs to Kyoto Talent / Wagashi Artisan Weaves Words into Traditional Japanese Sweets; Combining Traditions with Modernity

Chie Nanushigawa makes wagashi in Shimogyo Ward, Kyoto.

10:42 JST, June 22, 2024

KYOTO — In the world of traditional confectionary known as “wagashi,” Chie Nanushigawa is distinguishing herself with a distinctive style in which she combines Japanese and Western aspects by giving her products unique name.

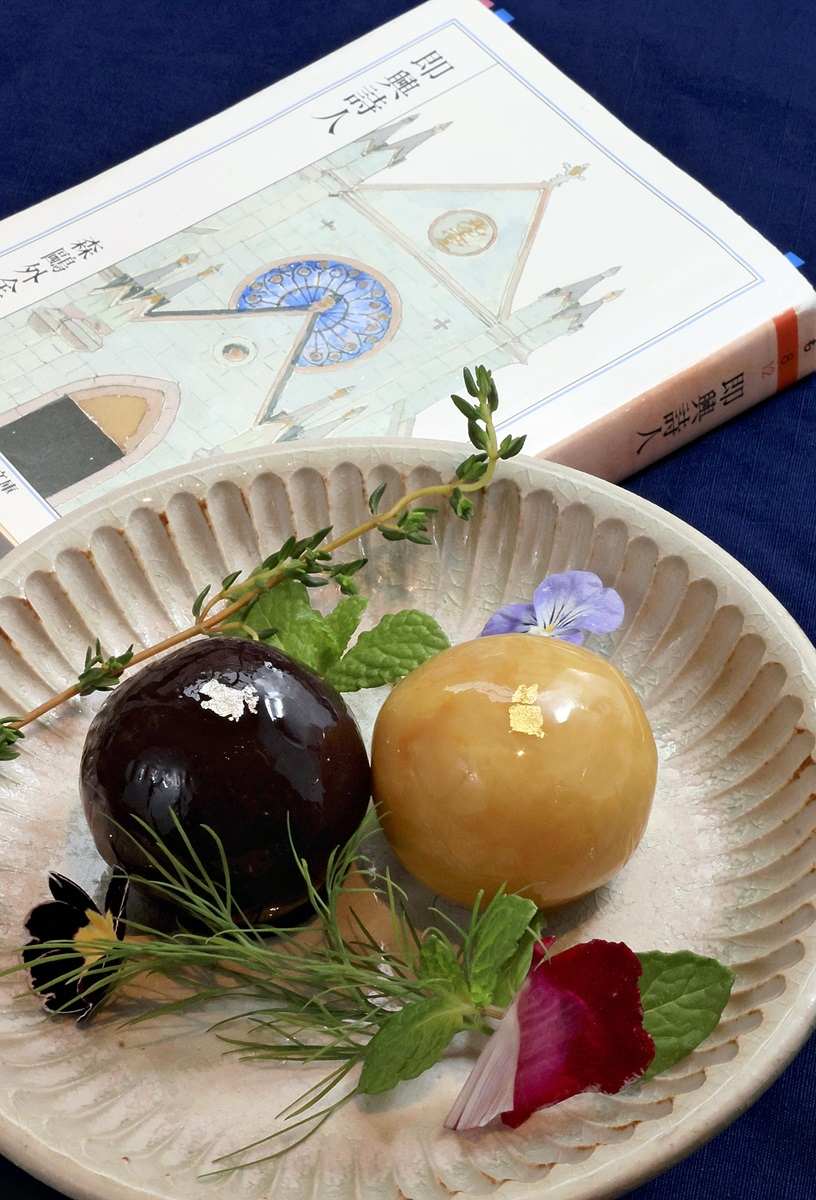

Take her signature wagashi product for example. Two pieces of round, red bean paste — one in brown and another in yellow — are accented with herbs and flower petals.

The product is named “Antonio and Lara” after the main characters in “Improvisatoren,” a novel by Hans Christian Andersen that was translated into Japanese by writer Ogai Mori (1862-1922). The bitterness of the life of poet Antonio is expressed with bitter caramel-flavored bean paste, while the passionate life of his wife-to-be Lara is presented with a sweet-and-sour bean paste mixed with mango. The sweets are served with an explanation to help people enjoy the blend of Japanese and exotic feelings.

Nanushigawa’s signature wagashi product “Antonio and Lara,” which was named after the main characters in the book “Improvisatoren” that Ogai Mori translated into Japanese

The distinctive names for her wagashi products are not limited to literary characters. “Tayutafu” (“drifting” in an old Japanese expression), “Komorebi” (sunlight through leaves) and “Otome no uta” (Maiden’s song) — I can’t help but feel like these names add depth to the taste and aroma to the sweets.

Clockwise from left: Tayutafu, Komorebi and Otome no uta

“Words are an indispensable part of wagashi that is directly related to the image and depth of the confection,” Nanushigawa said. “Sharing the words helps people learn about the sentiment and culture behind wagashi.”

Momentous encounter

Nanushigawa had a fateful encounter that changed her life in the autumn of her final year of university. During a visit to Kagoshima Prefecture to conduct research for her graduation thesis on traditional events, she became acquainted with an elderly woman. When they parted, the woman handed her a large ohagi sweet consisting of a rice ball wrapped in red bean paste. On her way home, Nanushigawa ate it on the train, and the sweetness filled her mouth.

“I felt nostalgic and somehow relieved,” she recalled. “I was able to experience a once-in-a-lifetime encounter in that moment.”

Despite having no knowledge of wagashi, she had no doubts about venturing into a new field. After graduating from university, she entered a confectionery school in Kyoto. The day after the entrance ceremony, she applied for a part-time job at Chokyudo, a wagashi maker in Kita Ward, Kyoto, that was founded in 1831. She learned the basics from the late factory manager, Shunichi Murakami, in the daytime and attended school at night.

“I didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted to do before then, so I was constantly impressed.”

Nanushigawa was surprised by the wagashi designs and presentations that evoke the seasons. Dozens of wooden molds are used for each season to make wagashi. For fresh wagashi, shades are created by hand to show boundlessly delicate colors, evocative of things like the sky at dusk. She was particularly fascinated with Murakami’s commitment to giving names to his confections, like “Ginyu Shijin” (troubadour) and “Chinshi” (contemplation).

Her pursuit of wagashi continued through the years, and 15 years passed before she realized it.

“She was diligent in honing her skills and meticulous enough to faithfully reproduce traditions,” a former colleague said.

Impressive expressions

In May 2020, Nanushigawa went independent and launched her own wagashi shop, “Kashiya Nona,” in Shimogyo Ward, Kyoto. She decided on “Kashiya,” which means confectionery shop, instead of wagashi shop out of a desire to allow others to see her sweets as something that goes well with coffee and black tea and also be enjoyed as a casual treat.

Wooden molds used for wagashi making

Initially developed to be paired with Japanese tea ceremonies, wagashi sweets are made mainly with rice flour and azuki red beans. They are designed to express the changing of the seasons through their shapes and colors. Nanushigawa appeals to the sense of taste by using seasonal fruits and herbs, as well as to the imagination by giving her sweets memorable names.

She established her distinct style thanks to a suggestion from her husband, who used to be a chef specializing in Italian cuisine.

At first, the two were at odds because her wagashi was aimed at creating a taste and texture of sweets that would not clash with green tea served in a tea ceremony. However, when she learned that Japanese confections had been developed with a combination of Chinese and Western cultures, she said she became aware of her own narrow-mindedness.

While always seeking “newer kinds of deliciousness,” Nanushigawa values the techniques and culture that have been passed down from generation to generation in Kyoto.

“To preserve the traditions — which impressed me when I knew nothing about wagashi — I want wagashi to be an easily accessible entry point for people to learn about traditions.”

***

If you are interested in the original Japanese version of this story, click here.

Top Articles in Features

-

Tokyo’s New Record-Breaking Fountain Named ‘Tokyo Aqua Symphony’

-

Sapporo Snow Festival Opens with 210 Snow and Ice Sculptures at 3 Venues in Hokkaido, Features Huge Dogu

-

Tourists Flock to Ice Dome Lodge at Resort in Hokkaido, Japan; Facility Invites Visitors to Sleep on Beds Made of Ice

-

High-Hydration Bread on the Rise, Seeing Increase in Specialty Shops, Recipe Searches

-

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Craftsman Works to Keep Tradition of ‘Kinran’ Brocade Alive Through Initiatives, New Creations

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan