Myanmar Will Continue Under Military Rule Even After Election, Ex-Ambassador Maruyama Says in Exclusive Interview

16:05 JST, January 7, 2026

Voters went to the polls in Myanmar on Dec. 28 for the initial phase of the country’s general election. Polling will also take place on Jan. 11 and 25.

Ichiro Maruyama, a former Japanese ambassador to Myanmar, spoke about the country’s rule under a military junta and the ongoing election during an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun. Maruyama, now 72, has long been engaged in Japan’s diplomacy with Myanmar and holds close ties with Aung San Suu Kyi.

***

The Yomiuri Shimbun: Has the military always been desperate to have control of the country?

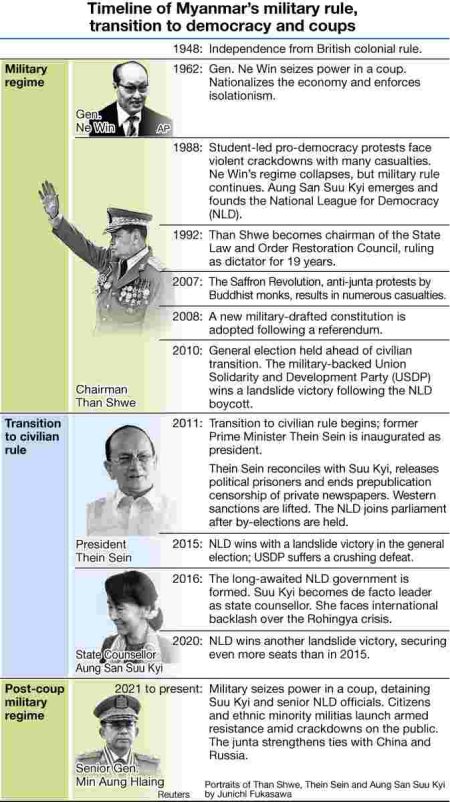

Ichiro Maruyama: I went to Myanmar for the first time in 1979, during the Ne Win socialist government under a military dictatorship. Then, no organizations other than the military were allowed and most administrative officials at ministerial status or lower were former military personnel. It was mostly the same under Than Shwe’s administration.

Immediately after independence from Britain, the military fought against the Karen group and the Communist Party of Burma, which fueled uprisings.

Government employees also took part in the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations. I vividly remember a senior military officer under the Than Shwe administration saying that is why they cannot trust civilians or civil servants. The officer said only the military bears the responsibility for the country.

Recently, Min Aung Hlaing, the supreme commander of the military, said in a speech that the military must remain in the role of political leadership, given historical context and the current situation. I feel such strongly held convictions have been passed down through the military since the 1962 coup.

Yomiuri: Some other Southeast Asian nations used to have developmental dictatorships or military regimes, too.

Maruyama: The impact of Myanmar continuing to have an isolationist policy until 1988 is very significant. Because of that, it had no engagement with the international community.

Around the same time, countries like Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines developed under developmental dictatorships, attracting foreign investment and building relationships with foreign governments and companies. Since they also associated with the United States and European nations as members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, there was no way that a military could seize absolute power and halt the economy in those countries.

Yomiuri: How has public consciousness changed in Myanmar?

Maruyama: Everyone hated Ne Win during his regime, and even a single bad word about him meant being taken away by the secret police. There were no jobs, and everyone was in poverty. The only way to get information on foreign countries was listening to shortwave radio stations like Voice of America or the BBC. People could not understand the differences between their country and others.

Public sentiment shifted dramatically after the 1988 pro-democracy movement in Myanmar. Suu Kyi [who was visiting her sick mother in the country from Britain] began speaking out against the military at rallies at that time. “You must leave politics,” she told the military, speaking in a dignified tone before the people — it was something the people themselves had always wanted to say.

She also had charisma as the daughter of [the nation’s founding father] Gen. Aung San. I think she truly is an amazing figure and someone for the people to look up to.

The international community also began paying attention to Myanmar. I think Myanmar would have become a forgotten country without Suu Kyi.

Yomiuri: People in Myanmar experienced freedom for the first time after the country’s transfer to civil government in 2011.

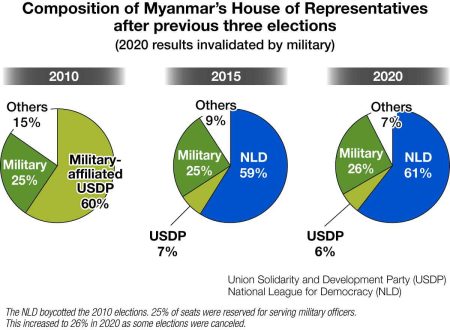

Maruyama: The administration led by former President Thein Sein was controlled by former military members, but the people preferred it to military rule. In the general election held in 2015, the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory, and the Suu Kyi administration was formed the following year. It was the first time in 54 years since the 1962 coup that the people had a government they themselves had elected.

There was such an incredible change in Myanmar [during the about 10 years of civilian rule] — enough to make the country considered the freest nation in Southeast Asia. But everything was destroyed in a day by a coup. The people’s disappointment and anger are immense, and will not fade away anytime soon.

Yomiuri: What will happen to the country after the election?

Maruyama: To get right to the point, the current system based on military rule will simply continue, and no real change will take place. Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing will become president, and ministers will be military figures in civilian clothing. The economy will deteriorate further.

Yomiuri: Is there any possibility of reform emerging from within the military?

Maruyama: There has never been an instance of someone from within the military top brass rebelling against the leadership. We cannot expect any positive developments like democratization or national reconciliation.

Yomiuri: How do you view the international community with regard to Myanmar?

Maruyama: One serious concern is that China has revealed its true nature. China has fully intervened in order to protect its national interests. It holds an enormous advantage as it can put pressure on Myanmar’s military regime [at any time], using a pro-China ethnic armed group.

Another concern is U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration showing no interest in Myanmar. Washington used to respond to such moves in and around Myanmar. The United States shocked the people by terminating Temporary Protected Status to Myanmar nationals and shutting down the U.S. Agency for International Development. I can say the United States’ indifference has turned Myanmar into a country where China and Russia can do whatever they want.

Yomiuri: How should Japan respond?

Maruyama: Japan has consistently urged the military regime to prioritize three things: Cessation of violence, the release of all detainees including Suu Kyi, and a return to democracy. Tangible progress on these three points is the minimum requirement for Japan to recognize [the Myanmar administration after the election], which is impossible under the current circumstances.

Yomiuri: What will happen to Japan’s official development assistance?

Maruyama: It is difficult and inappropriate to provide the assistance to Myanmar given it will continue to be led by the military after the election. On the other hand, strengthening support for the people of Myanmar who are in need through the United Nations and Japanese nongovernmental organizations is even more crucial.

Ichiro Maruyama

Maruyama joined the Foreign Ministry in 1978. He was stationed in Myanmar five times, for 27 years in total. Maruyama has a wide network of contacts in Myanmar, ranging from pro-democracy forces to senior military officers. He served as Japanese ambassador to the country from 2018 to 2024. He was born in Sendai.

***

ASEAN must take resolute stance

Myanmar’s military regime is accelerating the tightening of its ties with China, Russia and Belarus, including cooperation in the military sphere through such means as weapons procurement.

After the coup, ASEAN reached a five-point consensus with the junta, calling for steps including an immediate halt to violence by the military authorities. The junta has continued to ignore the agreement. It is increasingly signaling that it places greater importance on China and Russia than on ASEAN, raising concerns that this posture could, in time, affect stability across the Indo-Pacific region.

When ASEAN admitted Myanmar as a member in 1997, one reason was a fear that isolating the country would allow China to draw it wholly into its orbit. Then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and then Indonesian President Suharto pushed the decision through over more cautious voices.

Western governments and Aung San Suu Kyi fiercely opposed the move, arguing that it would lend legitimacy to the military regime. The junta did not end its repression. At one point, Hillary Clinton, then U.S. secretary of state, pressed ASEAN, saying it should consider expelling Myanmar if Suu Kyi were not released from house arrest.

When civilian rule took hold, relations with the West were normalized. But Myanmar has since swung back to military rule, tilting toward China and Russia again, leaving ASEAN feeling betrayed.

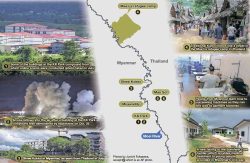

The regime is deploying Chinese- and Russian-made weapons in the civil war. China is developing a port and a special economic zone at Kyaukphyu on the Indian Ocean coast. Russia, too, is considering port development near Dawei, close to Thailand, at the junta’s request. It remains unclear whether the two ports being developed with the backing of the military regime will be for civilian use only. China also may seek to use the junta to influence ASEAN decision-making on issues such as territorial concerns in the South China Sea.

ASEAN, bound by its principle of noninterference in domestic affairs, has not imposed tough penalties on the junta. But firm measures are necessary in response to human rights abuses.

Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines have condemned the regime, and Ichiro Maruyama, a former Japanese ambassador to Myanmar, notes that “Japan needs to share a sense of urgency with ASEAN and work in coordination it.” Both sides should rebuild their approaches to Myanmar and act together in a coordinated manner.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza