15:21 JST, March 15, 2022

Development projects for oil and natural gas on the island of Sakhalin, located close to Japan in Russia’s far east, stand at a crossroads. The major Western oil companies that took the lead in development there have now decided to withdraw one after another, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Japanese trading houses and other entities have also taken part in the projects, but Japan is finding it hard to decide whether it should pull out of Sakhalin, which is an important source of energy for the nation.

Long-sought resources

“The development of energy resources on Sakhalin was a long-dreamed-of operation for Japan, which is resource-poor,” said a senior official of the Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry, in response to news reports of Western oil majors’ exits.

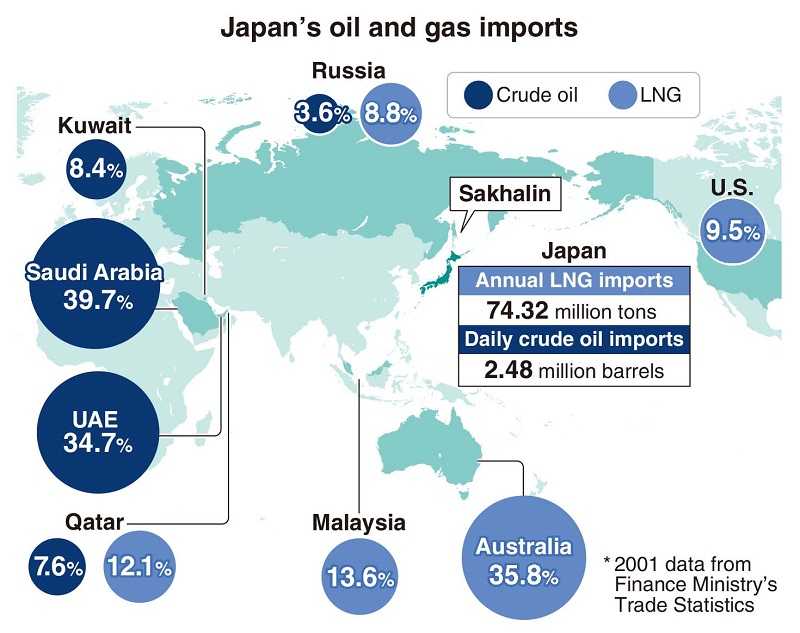

Japan started paying attention to oil and gas development on the northeast shelf of Sakhalin in the 1970s. At that time, Japan relied on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, which mainly comprises countries in the Middle East, for over 90% of its crude oil imports.

The first oil crisis in 1973, spurred by the Yom Kippur War, brought soaring prices for crude oil as well as societal concerns over possible shortages of goods. People’s lives in Japan were thrown into significant turmoil, with people buying up toilet paper in stores, for instance.

Japan’s government began exploring ways to diversify its energy sources and turned its eye to Sakhalin, which has large reserves of crude oil and natural gas and is geographically close to Japan.

The oil and gas resources in Sakhalin had been left untapped for about 20 years due to turmoil in the former Soviet Union and sluggish oil prices. In the 1990s, however, development projects went into full swing. With Japan and Russia both hoping at the time to forge closer relations over oil and gas development and production, Japan’s participation in the projects became a reality.

Sakhalin Oil and Gas Development Co., in which the Japanese government and other entities have a stake, has investments in the Sakhalin-1 Project, while Mitsui & Co. and Mitsubishi Corp. have investments in an energy development project called Sakhalin-2. This created a framework to supply crude oil and natural gas to Japan.

Local infrastructure

Sakhalin-1 started exporting crude oil in 2006, while Sakhalin-2 began shipments of liquefied natural gas in 2009. Before Japan became involved in the Sakhalin projects, its imports of crude oil and LNG from Russia were said to be insignificant.

Today, however, crude oil from Sakhalin-1 accounts for about 1% of Japan’s annual imports of that product, while LNG from Sakhalin-2 represents about 8% of its annual imports.

LNG, which is used as fuel for generating electricity and for making city gas, from Sakhalin-2 has a particularly huge presence. Sakhalin-2 LNG accounts for about 50% of the gas procured by Hiroshima Gas Co., about 20% for Toho Gas Co., and 10% each for Kyushu Electric Power Co. and Tohoku Electric Power Co. Thus, infrastructure in these companies’ respective regions is underpinned by LNG from Sakhalin.

Even if Japan’s government and companies pull out of the projects, crude oil and natural gas could continue being supplied from Sakhalin under existing long-term contracts. However, according to an official knowledgeable about the situation: “Russia might sanction Japan by not renewing the contracts. It might even cancel the contracts.”

It would not be easy to find alternative sources for procuring oil and gas under long-term contracts. Individual transactions could be possible, but “with prices fluctuating constantly, the cost burden would be huge if the price of natural resources soars, as seen recently,” an official at a leading city gas company said.

Higher procurement costs would lead to hikes in electricity and gas charges.

A tanker carrying liquefied natural gas arrives at Tokyo Bay in April 2009, shortly after full-fledged shipments of LNG started under the Sakhalin-2 project.

‘Strategically’

The government’s cautious stance over withdrawing from Sakhalin is prompted by its energy security policy of having diverse sources for oil and gas, without relying too much on the Middle East. There is also apprehension that its interests in Sakhalin could be taken away by China and other countries.

When Inpex Corp. announced its withdrawal from an oilfield development project in Iran in 2010, a Chinese company snatched up the interests. China in recent years has prioritized LNG as a fuel for generating electricity, as it emits relatively low levels of CO2. China became the world’s largest importer of LNG in 2021, exceeding Japan.

Economy, Trade and Industry Minister Koichi Hagiuda stressed at the House of Councillors Budget Committee: “Should some third-party country take Japan’s interests away, it would not serve as sanctions [on Russia]. At this point, we want to move wisely and strategically.”

Japan has been placed in a difficult position over Sakhalin — how can this country heighten pressure on Russia, which has been increasing globally, while also securing a stable supply of energy?

Top Articles in Business

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review

-

Narita Airport, Startup in Japan Demonstrate Machine to Compress Clothes for Tourists to Prevent People from Abandoning Suitcases

-

JR Tokai, Shizuoka Pref. Agree on Water Resources for Maglev Train Construction

-

Toyota Motor Group Firm to Sell Clean Energy Greenhouses for Strawberries

-

Japan, U.S. Name 3 Inaugural Investment Projects; Reached Agreement After Considerable Difficulty

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged