An instructor teaches Ukrainian soldiers how to operate a drone in Kyiv.

11:22 JST, August 30, 2022

Aug. 24 marked six months since Russia invaded Ukraine. Since the conflict began, new modes of war and related defense issues have come to light. This series explores possible lessons for Japan.

***

On the morning of July 25, a Chinese TB-001 strike and reconnaissance drone took off near Shanghai. The unmanned vehicle performed its first unescorted flight through the airspace between the main island of Okinawa and Miyakojima island in Okinawa Prefecture, before making a turn over the Pacific Ocean south of the prefecture’s Sakishima islands. The drone then flew over the Bashi Channel near southern Taiwan before returning to the Chinese mainland to land after a flight lasting some 12 hours.

Since the Defense Ministry first confirmed China’s use of the TB-001 drone about one year ago, China’s military has been improving its unmanned vehicle technology and used multiple test flights near Japan. On Aug. 4, when China was conducting large-scale military exercises in waters around Taiwan, a TB-001 and another drone model flew the airspace between Okinawa’s main island and Miyakojima, and then turned and flew back along the same route.

The TB-001 can photograph ships that are attack targets, send information about their location and conduct strikes using mounted missiles.

“China is steadily acquiring the ability to attack Taiwan with drones even from the Pacific Ocean side,” a senior Self-Defense Forces official said.

The Ukrainian military’s extensive use of drones has been a major factor behind the struggles of the Russian military during Moscow’s invasion of its neighbor.

The invasion appears to have heralded the arrival of the “drone age.” Ukraine’s military reportedly has thrown at least 6,000 drones into the conflict. These include small civilian drones that serve as “eyes” on reconnaissance missions, and Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 and U.S.-made Switchblade suicide drones that can attack enemy tanks and vehicles. Some commercial drones have been modified to carry small bombs for striking enemy targets.

Ukraine’s military has used the TB2 to destroy Russian transport vehicles and surface-to-air missiles. Russia’s military has had a hard time dealing with these drone attacks, which have highlighted a lack of communication between Moscow’s air and ground forces.

Some analysts predict that an emergency situation involving Taiwan could also lead to a battle in which the outcome is shaped by the use of drones. China is home to DJI Technology Co., the world’s largest maker of drones. Some observers have suggested China’s military could conduct a “saturation attack,” in which a massive number of drones are deployed to overwhelm an opponent’s defense systems and thereby seize low-altitude air superiority.

Scientists around the world were stunned in May when a team of researchers from China’s Zhejiang University revealed a technology that enabled a swarm of 10 drones to navigate through a natural bamboo forest without colliding and without using the Global Positioning System. These palm-sized drones are equipped with sensors that allow them to move autonomously, and they can instantly process data sent from a camera to pinpoint their geospatial location. The drones supplement each other’s information through data exchanges so they can avoid complex obstacles while in flight. This sort of technology could be adapted for drones meant for saturation attacks.

China is reportedly pushing ahead with the development of lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) that will eventually use artificial intelligence to select and strike targets.

Japan’s SDF had, until recently, not considered drones to be strategically important. As a result, the domestic defense industry has dedicated few resources to the field, and the nation’s drone development has fallen well behind that of other nations.

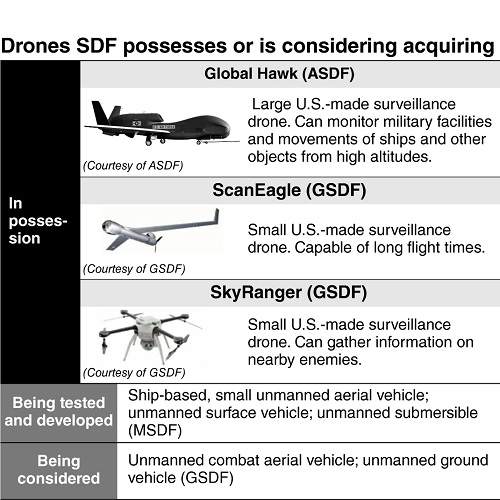

Japan’s unmanned vehicle fleet centers around drones used for warning and surveillance and collecting information, such as the Air Self-Defense Force’s U.S.-made Global Hawk surveillance drone and the Ground Self-Defense Force’s U.S.-made ScanEagle surveillance drone. The Defense Ministry plans to acquire attack drones and this fiscal year began a formal study to this end. The ministry envisions possibly using the commercial drones it already possesses for disaster response activities, but it is believed these drones would not be capable of taking part in combat.

The TB2’s flight range when using a terrestrial communication antenna is only about 150 kilometers. Drones with a longer range would be essential for any combat in the East China Sea or the Pacific Ocean. The SDF anticipates that such a conflict would involve fighting on and under the sea, so it has started research and development aimed at the introduction of unmanned vessels and submersibles. It will also consider adding unmanned land-based vehicles to the arsenal.

“The ministry should acquire all forms of unmanned assets and develop a strategy in which drones capable of flying long distances can strike a flagship,” said Kiyofumi Iwata, former GSDF chief of staff.

Japan’s own defenses against drones are weak. The SDF’s air defense system radar struggles to detect small drones, and responding to a saturation attack would be challenging.

In Ukraine, both the Ukrainian and Russian militaries have frequently used electronic warfare to incapacitate each other’s drones. The United States and Israel are developing laser weapons that could knock drones out of the sky. The Defense Ministry itself is accelerating efforts to counter enemy drones, such as by developing directed-energy weapons that shoot beams of high-power microwaves – the same kind of radiation used in microwave ovens – to disable unmanned vehicles.

The cost-effectiveness of drones also cannot be overlooked. If Chinese drones threaten to enter Japanese airspace, two manned ASDF jets will be scrambled in response.

According to estimates produced by Keio University Prof. Tomoyuki Furutani and others, operating a single drone costs about ¥70,000 per hour. Scrambling two F-15 jets costs up to ¥5 million. If the Chinese military assumes a strategy of using drones to drain Japanese resources even during peacetime, Japan might be forced to shoulder the massive financial burden of scrambling jets to counter them.

Masahito Yajima, commander of the Southwestern Air Defense Force responsible for the region around Okinawa and the Nansei Islands, is keeping a close eye on China’s military movements.

“Drones would be a game changer from both an operational and a cost perspective,” Yajima said.

Unmanned vehicles are one field where the SDF should be able to harness Japan’s technological prowess. “Japanese companies have these technologies,” a senior Defense Ministry official said. Making up for lost ground by acquiring attack, surveillance and various other drones has clearly become an urgent task for the government.

Top Articles in Politics

-

LDP Wins Historic Landslide Victory

-

LDP Wins Landslide Victory, Secures Single-party Majority; Ruling Coalition with JIP Poised to Secure Over 300 seats (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan Tourism Agency Calls for Strengthening Measures Against Overtourism

-

CRA Leadership Election Will Center on Party Rebuilding; Lower House Defeat Leaves Divisions among Former CDPJ, Komeito Members

-

Voters Using AI to Choose Candidates in Japan’s Upcoming General Election; ChatGPT, Other AI Services Found Providing Incorrect Information

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review