Tateyama Tunnel Trolley Bus Reaches End of the Line; Decommissioning Marks the History of Once-Thriving Post-WWII Electric Transportation

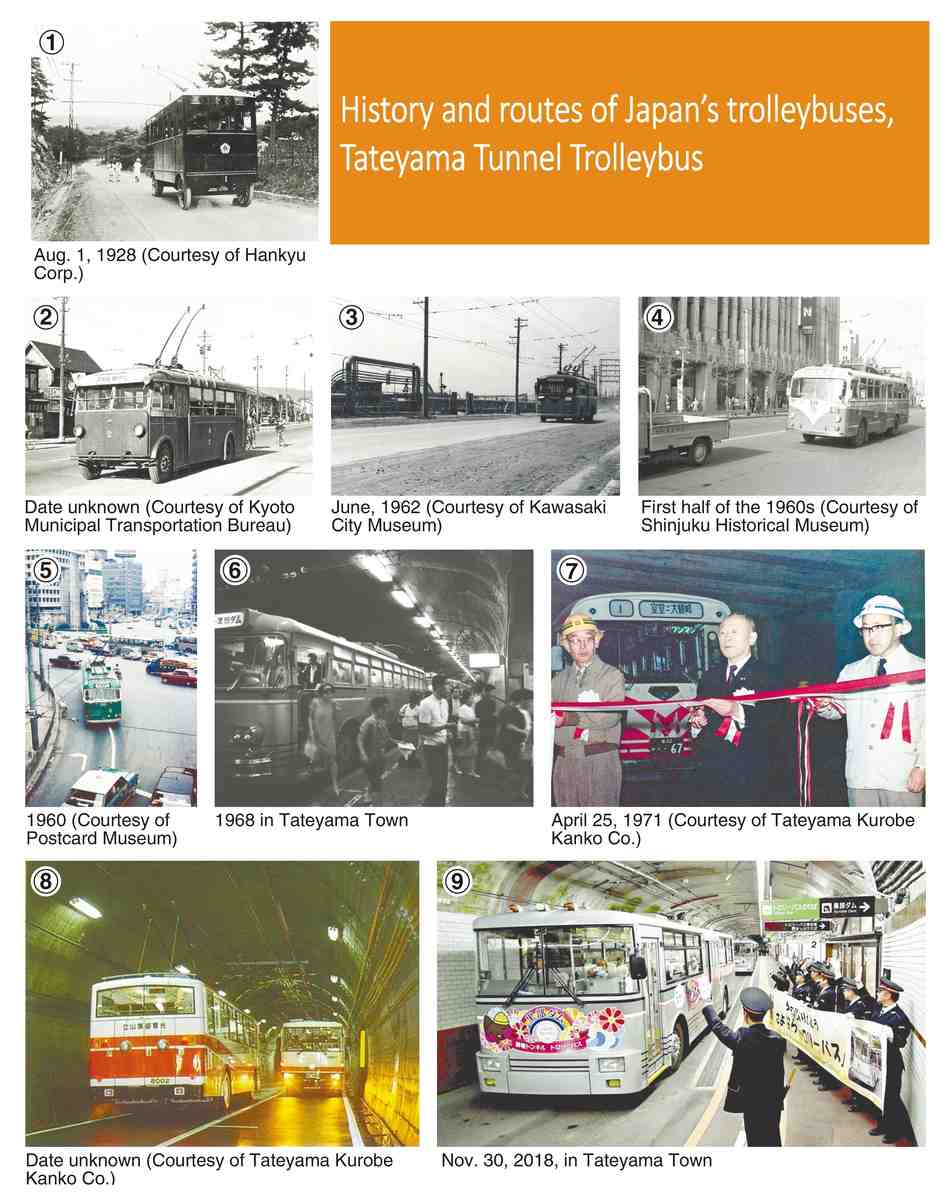

The last trolleybus departs at Murodo station as station staff gather to see the last run in Tateyama, Toyama Prefecture, on Nov.30.

13:07 JST, December 9, 2024

The Tateyama Tunnel Trolleybus stopped operating at the end of November. It had been carrying with it the thriving history of electric transportation in Japan, which had steadily been in decline since its post-World War II peak.

In years following the end of the war, trolleybuses served as a convenient means of transportation, especially in major cities, and were known for their low costs.

But they gradually disappeared from society as private cars became more commonplace. The end of the trolleybus line through the Tateyama Tunnel, the last left operating in Japan, will mark the end of its history.

Introduction in postwar years

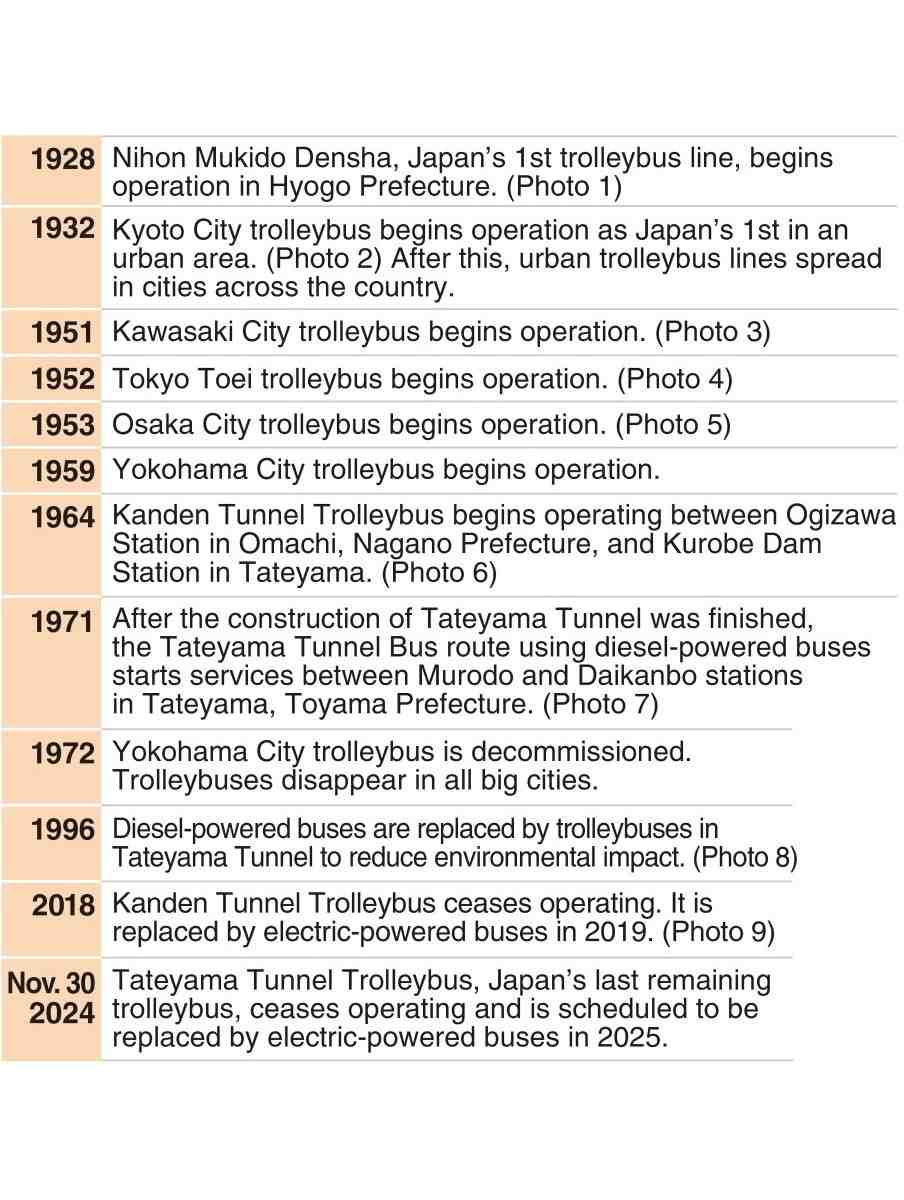

Japan’s first trolleybus is believed to have been Nihon Mukido Densha, opened in Hyogo Prefecture in 1928.

A hot springs bath resort had been developed at the time on a steep slope in the area of Kawanishi in the prefecture, and the line was introduced to reach it.

It ran about 1.3 kilometers from Hanayashiki Station to Shin-Hanayashiki station, near the hot springs, but was forced to close only four years later due to frequent operating issues.

However, trolleybus lines had the advantage of not needing to lay rail tracks and having lower introductory costs than trams, leading them to catch the eye of local governments as a means to expand inner-city transportation.

In 1932, when Nihon Mukido Densha went out of business, the Kyoto city government opened its own trolleybus line, the first in an urban area.

Japan then entered years of war, after which fuel shortages in part drove the introduction of more trolleybus lines.

By the 1950s, trolleybuses operated by municipal governments had opened in many big cities, including Nagoya, Kawasaki and Tokyo.

Itsuhiro Mori, 80, who was involved in The Kansai Electric Power Co.’s trolleybus business, said: “Trolleybuses could use existing tram substations. They were effective in supplementing public transportation in cities as they were used together with trams. They were useful for residents.”

Disappearing in cities

But the boom did not last long.

“At a time when fuel was in short supply, trolleybuses were able to run on electricity like a train while having the flexibility of a bus, proving convenient for operators,” said Prof. Kiyohito Utsunomiya of Kansai University, an expert of transportation economy studies and public transportation.

But he added, “From an opposite perspective, however, I can say that they were not wholly realized.”

Private cars became more common, leading to an increase in traffic and congestion. Demand for diesel-powered buses rose, as they were faster and did not require electric power supply or overhead wires.

The trolleybus vehicles themselves were expensive and consequently became less practical.

In 1972, Yokohama’s City trolleybus line was abolished, and trolleybuses disappeared from Japan’s urban areas.

Green tourism

On the other hand, trolleybuses still had the advantage of having no CO2 emissions.

For this reason, trolleybus lines were introduced along the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route, a popular tourist area famous for its rich natural environment. Trolleybuses there were given a new mission of transporting tourists.

In 1964, the Kanden Tunnel Trolleybus line began running between Ogizawa Station in Nagano Prefecture and Kurobe Dam Station in Tateyama Town in Toyama Prefecture, one of the sections in the Alpine Route.

Additionally, the Tateyama Tunnel, the last unfinished section of the Alpine Route, was completed in 1969.

In 1971, Tateyama Kurobe Kanko Co. introduced diesel buses, but exhaust fumes began building up in the tunnel due to an increase in tourists. In 1996, the company switched to trolleybuses.

“The fact that Tateyama Kurobe Kanko chose trolleybuses when electric vehicle technology was still undeveloped best spoke to its philosophy that ‘tourism can stand only if nature exists as a resource.’ It was an initiative ahead of its time given today’s rising awareness of nature preservation,” said Masayuki Moriguchi, 62, a transportation journalist.

Unique role

The Tateyama Tunnel Trolleybus became the only one left in Japan after the Kanden Tunnel Trolleybus was retired.

In part due to replacement parts no longer being manufactured, it finally ceased operations at the end of November and will be replaced by an electric bus next year.

The trolleybus will disappear altogether from Japan. However, Moriguchi praised the unique role it played in public transportation, unmatched by any other transportation system.

“The Alpine Route was a tourist destination that took passengers through the great outdoors and allowed them to change between eco-friendly transport such as ropeways and cable cars that don’t emit CO2. Trolleybuses there served as the prime example of eco-friendly transport.”

***

Trolleybus has last run in Tateyama

An operator drives a trolleybus in Tateyama Tunnel in October in Tateyama, Toyama Prefecture.

The Tateyama Tunnel Trolleybus, Japan’s last trolleybus line, ceased operation on Nov. 30, ending about 100 years of trolleybus services nationwide.

Since it started operation in 1996, the Tateyama Tunnel Trolleybus had safely carried 19,920,000 passengers without incident.

The trolleybus was used in Tateyama Tunnel because of its low environmental impact, as it runs on electricity, which powers the bus via overhead cables. The bus traveled between Murodo and Daikanbo in Tateyama, Toyama Prefecture, for 10 minutes at a maximum speed of 40 kph.

However, as trolleybus parts are increasingly difficult to procure, it was decided to end the operation.

Many fans and tourists went to catch its final run on the Tateyama Kurobe Alpine Route on the last day, bidding farewell to the last trolleybus.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time