SDF Seeking Ways to Distinguish Proper Guidance and Harassment; Leaders Hope to Create Common Understanding of What Is Appropriate Instruction

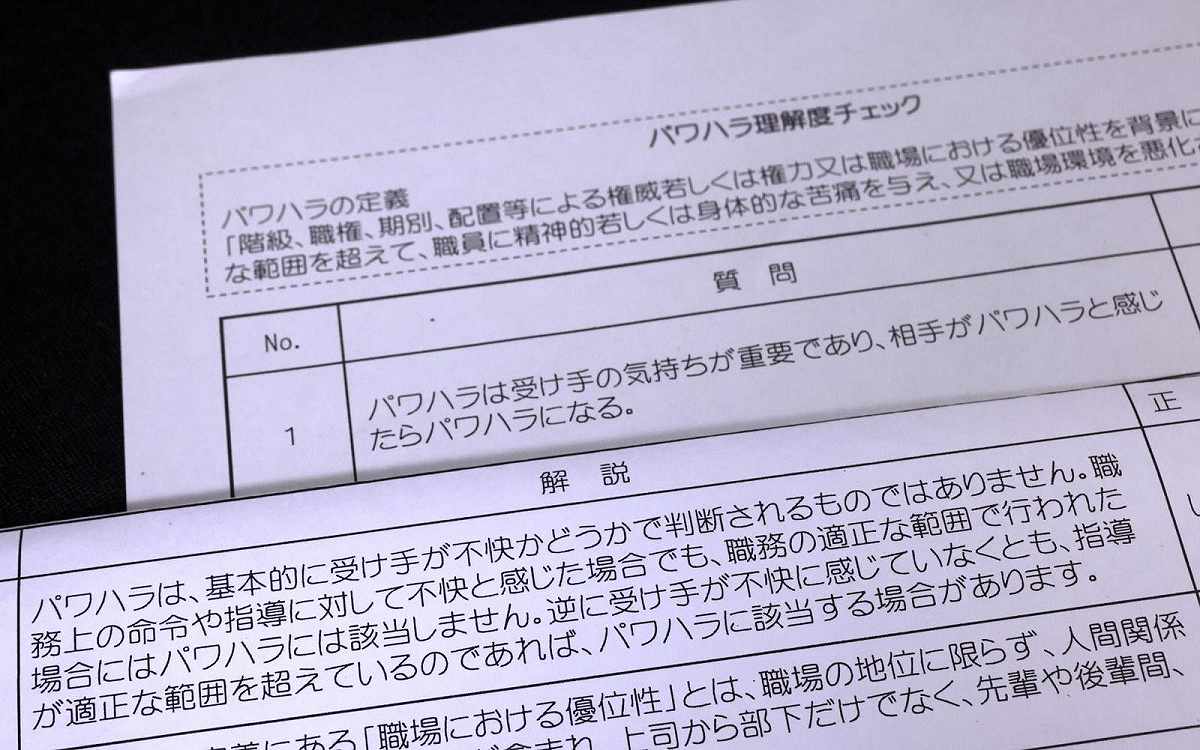

Documents distributed by the Ground Self-Defense Force to all its members to help them deepen their understanding of harassment.

21:00 JST, November 23, 2024

As the Self-Defense Forces try to root out all forms of harassment, they are struggling to make members understand where the line sits between proper guidance and “power harassment,” a form of harassment in which the perpetrator takes advantage of their superior position in the workplace over their victim.

Some SDF personnel even hesitate to give necessary guidance and instructions because they are afraid of being reported for harassment. The SDF is continuing to seek ways to strike a balance so it can train its members to be able to respond to tough situations such as emergencies and natural disasters without allowing harassment.

Hesitancy among senior staff

“Whenever I use strong language, I am immediately told I am harassing others,” said a senior SDF officer and former member of an aircraft unit, expressing concern for the recent atmosphere in the SDF.

In flight training sessions, small mistakes can put lives at risk. When a helicopter takes off from and lands in a narrow area, a pilot tilting the joystick even a centimeter beyond the correct angle for just a second greatly increases the risk of crashing into the surrounding buildings.

In one training session, an SDF member who was piloting a helicopter was about to make an operational error. A member who was there to guide them immediately stopped them, saying, “Watch out! What are you doing?” Later, the trainee claimed that the instruction was so intimidating that it was “power harassment.”

An investigation concluded that the guidance had been appropriate. However, the trainer who was investigated became so depressed that they lost passion for their work, according to the SDF. “There are more than a few cases like this. Verbal abuse is unacceptable, but giving instructions in a strict tone of voice is sometimes necessary in training sessions where lives could be at risk,” a senior official in the same unit lamented.

“Some members are hesitant about giving necessary guidance because they are excessively afraid of being reported for harassment by their subordinates,” Gen. Yoshihide Yoshida, chief of staff of the Joint Staff of the SDF and the SDF’s top uniformed officer, said at a regular press conference in September. “Our challenge is now to teach our members the distinction between necessary guidance and harassment.”

Reports up fivefold

Following a case in which a female former Ground Self-Defense Force member went public under her real name with the sexual abuse and harassment she had suffered while in the GSDF, the Defense Ministry conducted its first special inspection regarding harassment in 2022. It announced in December 2023 that it had punished 245 SDF members for power harassment and other misconduct.

This led more people to begin to see harassment as a problem. Before then, it was common for people to believe that rough language was just a part of passionate guidance. Last fiscal year, the number of reports about power harassment made to a hotline set up within the ministry reached about 1,500, about five times the number made in 2017.

While it is now easier for victims to be heard, an increasing number of cases are arising in which it is difficult to judge whether or not the behavior at issue constitutes power harassment.

According to the ministry’s directive, “power harassment” consists of three key elements: (1) taking advantage of one’s higher rank, seniority or other superior position, (2) going beyond the reasonable scope of one’s duties and (3) causing mental and physical distress. Whether an act constitutes “power harassment” or not is judged not solely by how uncomfortable the act made the other person feel, but in a comprehensive manner, taking into account why and how the actions were committed and whether they were ongoing.

However, a ministry official said: “Some members are given strict guidance because they make the same mistakes over and over. However, they forget what they are taught and complain that they are always singled out for scolding.”

Creating shared understanding

From the start, there was concern that such issues might come up. A set of proposals compiled in August 2023 by an expert panel set up by the ministry to consider anti-harassment measures pointed out that there might be a gap in understanding between superiors and subordinates of the distinction between proper guidance and power harassment. It suggests that the SDF should establish clear criteria to create a shared understanding between all members.

The SDF has begun taking measures to address the situation. In July and August, the GSDF distributed documents to all of its more than 130,000 members, presenting 10 example cases and asking them to answer whether or not each would constitute power or sexual harassment. To help SDF members deepen their understanding of harassment, the documents also presented specific criteria for judging harassment using specific examples that are often misunderstood.

“An increasing number of SDF personnel now consider power harassment unacceptable. However, there is no shared understanding of what it consists of,” a GSDF member said. “Carrying out dangerous missions requires relationships of trust between superiors and subordinates. We need to make sure to have our members have a common understanding of what proper guidance is.

Top Articles in Politics

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet Appointees from Previous Term

-

Japan’s Govt to Submit Road Map for Growth Strategy in March, PM Takaichi to Announce in Upcoming Policy Speech

-

LDP Wins Historic Landslide Victory

-

LDP Wins Landslide Victory, Secures Single-party Majority; Ruling Coalition with JIP Poised to Secure Over 300 seats (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan