The Ajinomoto National Training Center in Kita Ward, Tokyo

14:21 JST, March 23, 2023

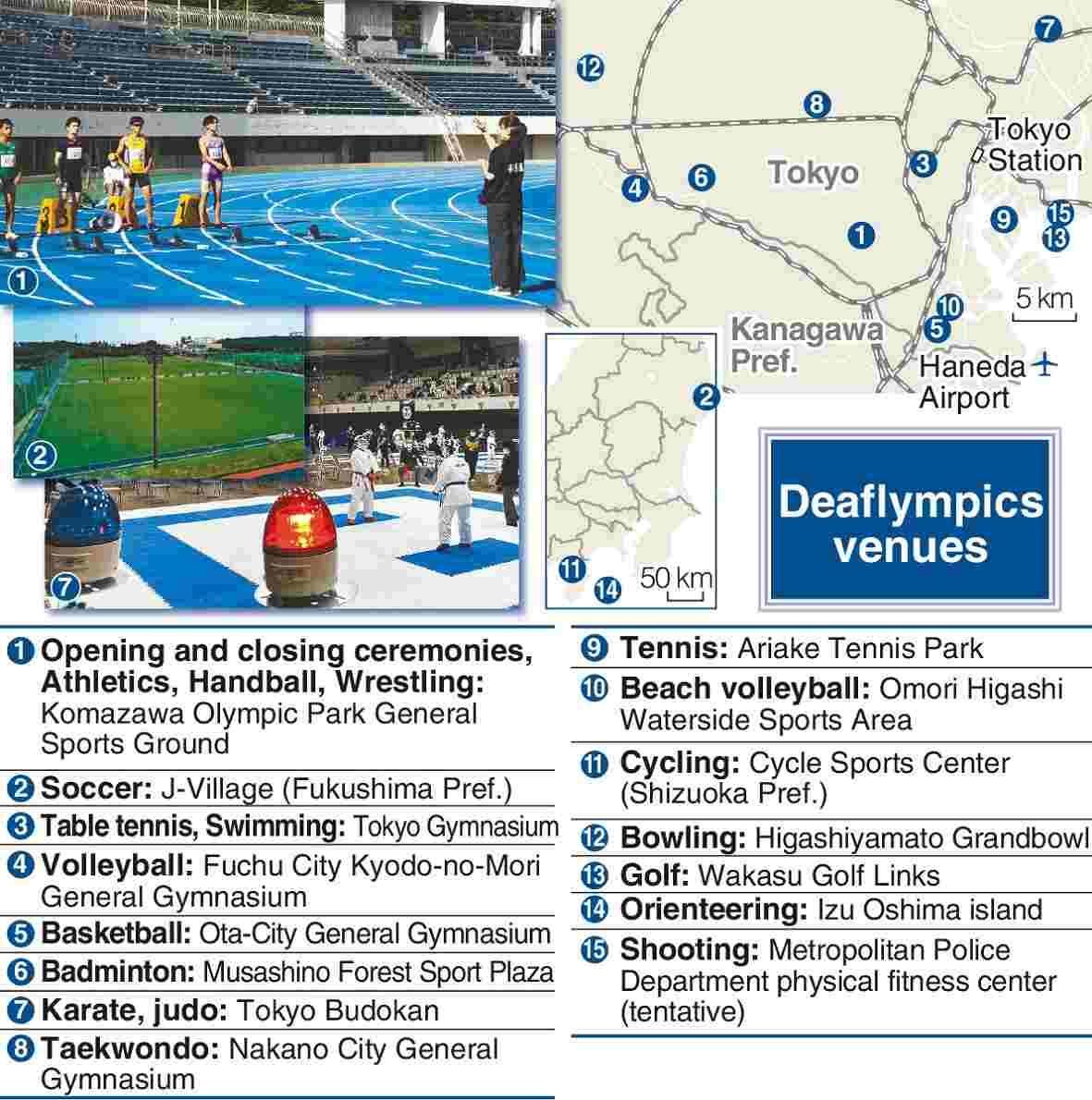

Japan is stepping up preparations to host the Deaflympics in November 2025.

It will be the first time for the international sporting event for people with impaired hearing to be held in Japan. Presently, activities geared towards making the mainly Tokyo-based event run smoothly — such as securing sign-language interpreters — are intensifying as the clock ticks down.

On Feb. 5, a mixed-ability karate competition was held at the Tokyo Budokan hall in Adachi Ward, Tokyo, which is scheduled to be used for the Tokyo Deaflympics. The event drew athletes ranging in age from children to adults, and included medalists from last year’s Brazilian Deaflympics.

“My goal is to compete in the Tokyo Games,” said 16-year-old Tomoshin Sato, a first-year high school student with a hearing impairment. “I want to learn techniques from many athletes.”

In recent years, Japanese organizations involved with Deaflympic sports have helped train athletes and support their athletic aspirations. As a result of this backup, Japan won a record 30 medals at the Brazilian Games. However, holding training camps in Tokyo and having athletes attend competitions proved difficult, due to funding and other factors.

To ensure a good medal haul at the Japan Deaflympics, various agencies are striving to improve support for Deaflympians, who still lag Japanese Olympians and Paralympians in terms of training environment.

The Japan Sports Agency and the Japanese Federation of the Deaf, among other bodies, hope to make the Ajinomoto National Training Center (NTC) in Kita Ward — the country’s premier sports training base — available for use by hearing-impaired athletes from next fiscal year.

The Japan Institute of Sports Sciences, which sits next to the NTC, provides athletes with specialized training, nutritional advice and medical and scientific support — a major advantage for top-class athletes keen to improve their performance levels.

Prior to the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics, the NTC put priority on competitors in those events. Following the Games, however, the center opened its doors to hearing-impaired athletes, too. The federation is currently working with the sports agency and others to further promote use of the facilities by Deaflympians.

According to the federation, many Deaflympians have expressed a strong desire to use the NTC as soon as possible.

“The athletes are aware that the [NTC] provides a superlative training environment and first-class support,” said Naoki Kurano, director of the federation’s head office.

Securing funding

Some local governments provide support of up to ¥400,000. In December, the Tokyo metropolitan government enrolled 29 hearing-impaired athletes in an existing program that supports disabled athletes with Tokyo ties — the first inclusion of such sportspersons.

The program was originally geared toward para-athletes, but after Japan was chosen to host the Deaflympics, the metropolitan government decided to add hearing-impaired athletes, too.

The program provides each athlete with an annual subsidy of up to ¥400,000 to attend sports meets, and for other purposes.

Said program participant Ai Iwabuchi, 29, a member of the Japanese women’s soccer team at the Brazil Games: “I think the environment [for hearing-impaired athletes] is gradually changing. I want to become an athlete who people feel happy to support.”

Saitama Prefecture has also started including hearing-impaired athletes in its support program, which formerly was geared toward para-athletes, providing annual subsidies of up to ¥200,000, among other benefits.

Sign-language interpreters

A major challenge for the Games’ organizers is securing sign-language interpreters. International sign language will be the official language of the Games, and the federation began recruiting interpreters in February.

The exact number of interpreters needed is not yet known, but the federation is continuing its recruitment drive. The federation had been holding study sessions on signing since before Tokyo was selected to host the Games. It also is considering stationing interpreters at the Games’ headquarters and having venues connect with the headquarters online.

Deaflympic sports organizations include able-hearing coaches and referees who cannot provide sign language interpretation. In light of this, efforts are underway to train sign-language interpreters who are familiar with sports.

Prior to the Feb. 5 karate competition — the sixth of its kind — the organizer had participating referees learn basic sign-language expressions, such as “shobu hajime” (start the match).

“Hearing impairment is increasingly understood among non-disabled people,” said Tomoko Takahashi, head of Japan Deaf Karate-do Federation. “Each year, more and more staffers are learning to use sign language.”

Kurano commented on the positive aspect in the long term.

“International sign-language interpreters will have many opportunities to be active following the Deaflympics. The event will leave behind legacies, including sign-language interpreters who are familiar with sports.”

Related Tags

Top Articles in Sports

-

Aonishiki Tops Atamifuji in Playoff to Win New Year Grand Sumo Tournament in Ozeki Debut

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Kokomo Murase Comes Out on Top After Overcoming Obstacles, Aiming for Greater Heights in Competition

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Olympics-Torch Arrives in Co-Host Cortina on Anniversary of 1956 Games

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japan’s Athletes Arrive in Italy for Milano Cortina Winter Olympics; Other Athletes to Arrive from Now

-

Sumo Scene / What’s in a Sumo Name? The Reason Why the New Year Tournament Is Called the January Tournament

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review