Earth Overheating / Global Warming Stokes Waves of Refugees, Sparking Social Tensions

Refugees from Somalia receive water at a refugee camp in Dadaab in eastern Kenya.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

7:00 JST, December 5, 2023

After an extreme summer of “global boiling,” the United Nations is holding its COP28 climate summit in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. This is the first installment of a new series that looks at how climate change is threatening people’s livelihoods and measures being taken globally.

***

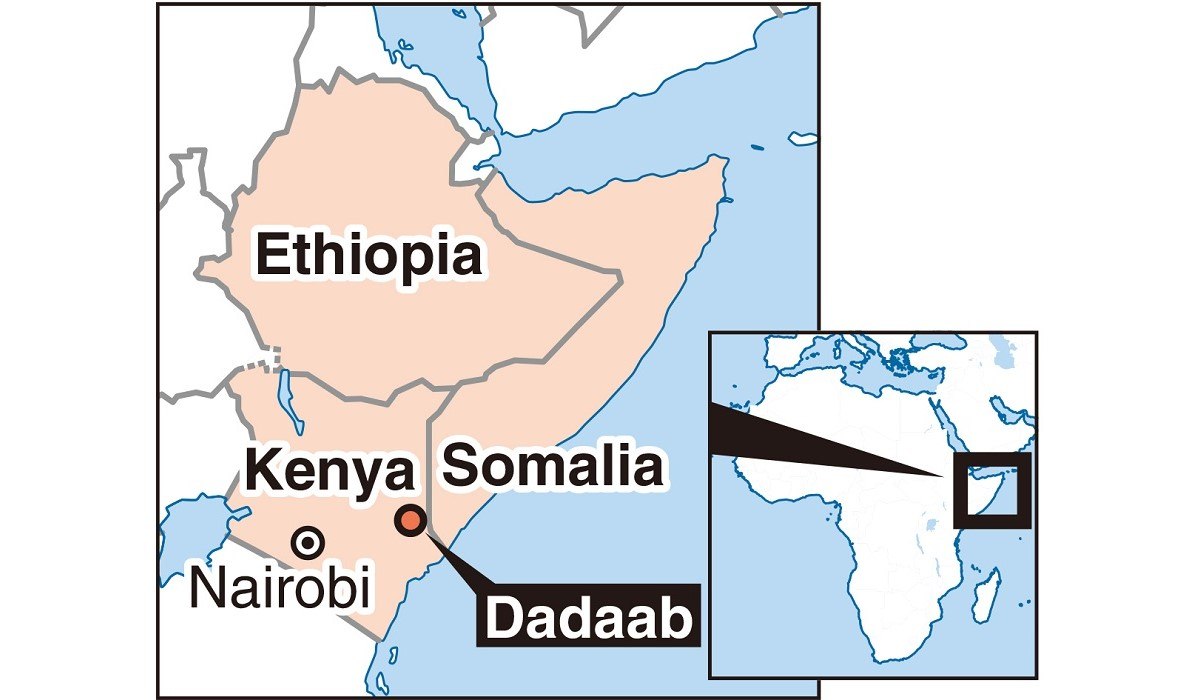

Dadaab, a town in eastern Kenya, sits on dry, dusty land, with few trees. Refugees from neighboring Somalia and Ethiopia pour into the town every day, seeking shelter at Africa’s largest refugee camp. They build crude tents with rags and branches on the rust-colored earth for a place to sleep. The refugee population has swollen to some 370,000 people.

In the Horn of Africa, a geographic area that includes Somalia, one of the world’s poorest countries, there has been almost no rain during rainy seasons for the last six years, creating the Horn’s worst drought in 40 years. Crops have withered in the field, and goats and cattle have died in scores. People who have lost the means to support themselves abandon their homes and cross the border.

When Takeshi Moriyama, senior emergency coordinator for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, which runs the refugee camp, visited the site in May, the wretched conditions left him speechless.

Refugees were emaciated, with too little aid to meet demand. Cholera was rampant due to poor hygiene. Security is yet another problem, with members of the Islamic militant group Al-Shabaab having slipped into the area and abducted foreign staff from aid organizations. But aid workers still tend to their duties, looking out for their own safety.

Last month, flooding from sudden heavy rains submerged most of the camp, keeping many supplies from reaching the refugees. Even so, a woman, 33, with eight children reportedly told a staff member at the local aid office, “Even if I go back to my hometown, I won’t be able to give my children food and water, and I’ll have no hope of survival. I have no choice but to stay here.”

In Somalia, farmers reportedly hand over their sons to Al-Shabaab fighters so they have fewer mouths they need to feed, and mothers engage in prostitution to feed their babies.

“It’s the most vulnerable, such as women and children, whose lives are threatened by climate change,” Moriyama said.

In recent years, people forced to leave their homes and communities due to climate change, such as from floods, droughts and other extreme weather conditions, have come to be called “climate refugees.”

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, the number of people displaced within their own countries due to climate change reached 22.3 million in 2021, far exceeding the 14.4 million who were displaced internally due to conflict. The World Bank estimates that 216 million people will be forced to migrate by 2050.

And more climate refugees means more social unrest. Honduras, in Central America, was hit by two major hurricanes in 2020, affecting more than 4.6 million people. Gang activities then spiked, making life less secure and driving up poverty. Hundreds of thousands fled to the United States, Mexico and other nearby countries.

But the migrants have caused friction in the countries they have fled to. Authorities detain them as illegal immigrants, and local residents stage demonstrations against them.

Countries are taking desperate measures to protect their citizens from climate change.

Most land in the Maldives, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, will be submerged by 2100 due to rising sea levels, it is said. The government is building an artificial island, called Hulhumale and measuring about four square-kilometers, in waters about five kilometers from the capital, Male. People have already started moving to the island, pushing its population up to about 65,000 people, or more than 10% of the population for the whole country. Preparations are also underway to build a floating city of houses and hotels on the sea, with the project set to finish around 2028.

The Pacific island nation of Fiji has moved further inland some coastal settlements, which are vulnerable to waves.

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi will be the first head of the organization to join a COP climate summit. At a press conference during his visit to Japan in October, Grandi stressed the importance of discussing measures to help climate refugees. He said a vicious cycle has been created, where migration by climate refugees leads to conflict, and each conflict brings yet more refugees.

Will climate change-induced tides reach Tokyo Skytree?

The accelerating rise in sea levels around the globe is one of the factors creating climate refugees.

Antarctica’s winter sea ice extent has become the smallest in recorded history, the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center announced in September. The southern continent is estimated to contain 90% of the ice on Earth.

This year, the sea ice extent even at its peak was 16.96 million square kilometers, 1 million square kilometers less than the lowest previously recorded in 1986. This ice loss is 160% greater than the area of the Japanese archipelago.

The U.S. center noted that Antarctica sea ice is likely decreasing because oceans are warming globally. In August, the global average sea surface temperatures reached a record high.

Researchers are closely monitoring the rapid melting of ice shelves extending into the ocean from coastlines. Ice shelves stop ice sheets on the continent from flowing into the ocean. If they melt in the warmer seawater, ice on land will continue to flow into the ocean, accelerating the loss of ice.

The British Antarctic Survey estimates that even if the temperature rise since the Industrial Revolution is kept below 1.5 C, the speed of ice loss will be three times that observed in the 20th century.

Melting antarctic ice is observed at the beginning of this year.

The U.K. institute noted that stopping ice melt may not be possible despite taking measures against global warming. It warned that nations across the world will need to prepare for sea level rises of several meters over the next few centuries.

A report by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that if the global average temperature rises by 2 C above the pre-industrial level, the average sea level in the year 2100 will rise by up to about 60 centimeters. If sea levels rise, island nations could be submerged and coastal areas of Japan would face more risks of erosion and flooding caused by high tides and waves.

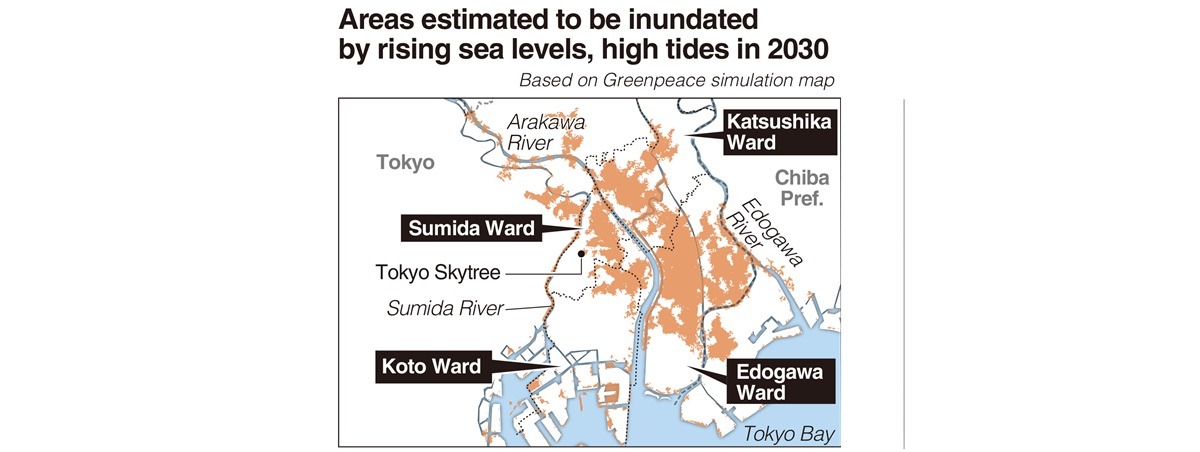

In 2021, Greenpeace estimated the damage that would occur if no proactive measures against global warming are taken. The global environmental NGO reported that by 2030 for Tokyo, a giant typhoon inducing high tides would flood an area of 79.28 square kilometers. It would encompass the lower reaches of the Sumida, Arakawa and Edogawa rivers, affecting 830,000 people.

Seawater would also travel up the waterways to the Tokyo Skytree in Sumida Ward.

“There are fears that the damage from high tides will be intensified by the combined forces of rising sea levels and more powerful typhoons,” said Hisayo Takada, project manager of Greenpeace Japan. “Tokyo is at risk of being inundated by floodwaters higher than adult height.”

To prepare for rising sea levels, the central government sent a notice in 2021 to the 39 prefectures with coastlines requesting them to revise by fiscal 2025 their basic coastal protection plans to take into account the possible effects of climate change.

In 2020, the Chiba prefectural government increased the height of the 3.8-meter seawall at Hamakanaya Port in Futtsu by 30 centimeters. The seawall had been damaged by high waves caused by Typhoon No. 15 the previous year. After receiving the central government’s notice, the prefecture recalculated the required height increase and found that it should have been raised by 80 centimeters.

Chiba Prefecture also calculated that the rise in tide levels in Tokyo Bay varies from 40 centimeters to 1.4 meters depending on the topography and wind direction in each area. Revising the plan is therefore likely to take a considerable amount of time.

“Our finances and budgets are very tight these days,” said a deputy director of the Chiba prefectural Port and Harbor Division. “It is difficult for us to accurately calculate maintenance costs based on uncertain predictions for the distant future.”

Shigeru Aoki, an associate professor of marine physics at Hokkaido University and specialist on climate change, said: “Even if we increase the size of dikes, it is only a stopgap measure and far from sufficient to deal with natural threats. We have no choice but to formulate fundamental measures against climate change to reduce greenhouse gases, such as raising people’s awareness of the need for decarbonization.”

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

3,000 Accounts Posting, Spreading Content Critical of Japan on X;...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Sakamoto Serves as Flag Bearer; Japan Earns ...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: There Were Cheers across the Country, after ...

-

A Packed Bus Plunges off a Nepal Highway, Killing 19 and Injuring...

-

Luna Sea Drummer Shinya Dies at 56; Powerful Drummer Behind ‘Desi...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: ‘Magical’ Italian Games Close wi...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Riku-Ryu Duo Stick Together During Closing C...

-

Emperor Receives Well-Wishes from Public on His 66th Birthday

Popular articles in the past week

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Japan's Govt to Submit Road Map for Growth Strategy in March, PM ...

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All E...

-

U.S. Firm to Build Training Hub in Fukushima N-plant for Debris R...

-

Japan, U.S. Name 3 Inaugural Investment Projects; Reached Agreeme...

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major C...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reco...

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many Peop...

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages C...

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Befor...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Girls Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan