World War II Battleship Yamato Was Outdated From the Start; Unable to Compete With Newly Developed Warplanes

Isamu Nakakura talks about a test run of the Yamato battleship, in Saeki Ward, Hiroshima, on April 1.

6:00 JST, April 8, 2025

The battleship Yamato was a symbol of the Imperial Japanese Navy — the largest warship of its kind ever built — but it was no match for the newly developed warplanes of World War II.

As this month marks the 80th anniversary of the sinking of the Yamato, a person involved in its construction and a former crew member spoke to The Yomiuri Shimbun about the horrors of the war.

In late October 1941, just before the start of the Pacific War, then 17-year-old Isamu Nakakura was in the bottom of the Yamato, which was making a test run off Sukumo, Kochi Prefecture.

Nakakura, who now lives in Hiroshima at the age of 100, worked at Kure Kaigun Kosho, a military factory run by the Imperial Japanese Navy in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture. The test run was conducted to confirm the mechanical performance of the Yamato ahead of its handover to the navy.

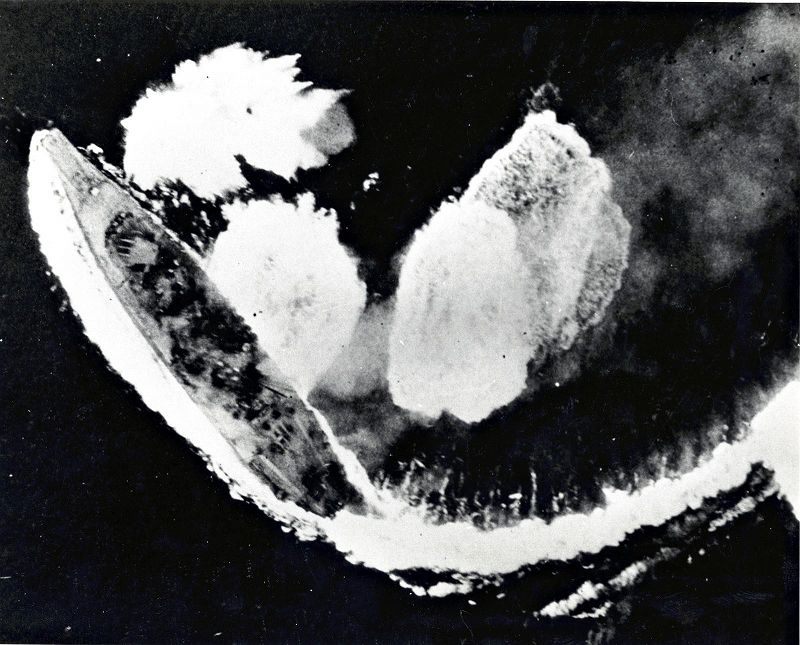

The Battleship Yamato makes a test run off Sukumo, Kochi Prefecture, in October 1941.

The 263-meter-long ship sailed forward, cutting through the waters at its maximum speed of about 50 kph. Nakakura stood in the rear section of the bottom deck, near the Yamato’s rudder and screws, and recorded the movement of oil hydraulic cylinders related to the steering.

Each time the ship moved sharply, Nakakura felt a thrilling sensation.

Powerful, low noises echoed in his ears. He was overwhelmed by the power of the Yamato.

Nakakura became an apprentice worker at the factory in 1938. On his commute to work, he could hear the sound of steel plates being bonded with rivets from a shipbuilding dock that was concealed from view.

During construction, the Yamato was called ship No. 1.

“It’s surprisingly wide,” Nakakura thought when he saw the unveiled Yamato for the first time. “It should be an unsinkable warship that can’t be damaged by one or two torpedo hits.”

The Imperial Japanese Navy built enormous battleships to prepare for decisive fights between fleets, in which battleships would exchange naval gun fire.

However, only eight days before the Yamato’s construction was finished, the Imperial Japanese Navy itself proved that warplanes had become superior to battleships. Japanese airplanes attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, sinking or seriously damaging eight U.S. battleships moored there.

“The Yamato was built with many of the latest technologies at the time, but it had already become outdated,” Nakakura recalled.

Later, Nakakura joined the navy’s unit for training new recruits. After the end of the war, he participated in hearings for the United States’ Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, which studied the atomic bombs’ effects on human bodies.

Nakakura witnessed survivors suffering from the aftereffects and felt the cruelty of war deeply. He has also continued to think about how lives should be valued, imagining the soldiers who died on the Yamato, which had been left behind by the changing times.

On speaking to younger generations who do not know much about the war, Nakakura said: “I don’t want them to think peace is a matter of course. I want them to learn about the international situation and consider what war is.”

‘Couldn’t compete with planes’

Isao Kimura

Former Yamato crew member Isao Kimura recalled: “More than anything, it was enormous. I was surprised by a ship having an elevator.” He became a member of the Yamato’s crew in 1942.

Now 104 years old, Kimura lives in Ishii, Tokushima Prefecture. He said the Yamato was equipped with air conditioners and had beds instead of hammocks for the crew. Moving inside the huge ship was called “traveling.”

However, the battleship only rarely departed for battle. The figure of the moored battleship was sometimes ridiculed as the “Yamato Hotel.”

Kimura often delivered telegrams to Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the navy’s Combined Fleet, who was aboard the Yamato. In those days, battles over Guadalcanal Island in the southern Pacific Ocean had been increasingly fierce.

Kimura was struck by the bitter expressions on Yamamoto’s face, probably because the telegrams were notifying him of the difficult battles.

In March 1943, Kimura was transferred to the cruiser Tone and thus left the Yamato. In October 1944, he participated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, in which the Musashi, a sister ship of the Yamato, was sunk by U.S. warplanes.

Kimura said he felt the changing times on the front line, saying, “The battleships couldn’t compete with the large number of planes.”

Collecting newest information

Shinichi Nakazawa, a Maritime Self-Defense Force officer and associate professor of the National Defense Academy, said: “During the war, recognition of the Yamato was low because it was built secretly. After the end of the war, the existence of the tragic battleship became widely known, and it resonated among the Japanese people, who tend to like an underdog.”

“It was the most advanced battleship and was being built based on the reasonable assumption of a strategic scenario where decisive battles would be won by fleets,” Nakazawa said. “But when it was completed, it couldn’t handle the new type of battles in which warplanes played the leading role.”

Rapid developments in military technologies are also occurring today. In Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, unmanned aerial vehicles have totally changed the battlefield.

“Technologies change with dizzying speed,” Nakazawa said emphatically. “The history of the Yamato indicates that collecting a wide range of the latest information is necessary for improving defense capabilities.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan