Former elementary school classmates Taiga Ide, left, and Shinya Niitsuma visit a park in their hometown of Tomioka, Fukushima Prefecture, on March 2. The park is fenced off as decontamination continues.

13:37 JST, March 14, 2022

Taiga Ide opened the window, which still did not have a curtain, and breathed in the breeze of the approaching spring. It was March 1, and he was ready to start a new life in a housing unit run by his hometown of Tomioka, Fukushima Prefecture.

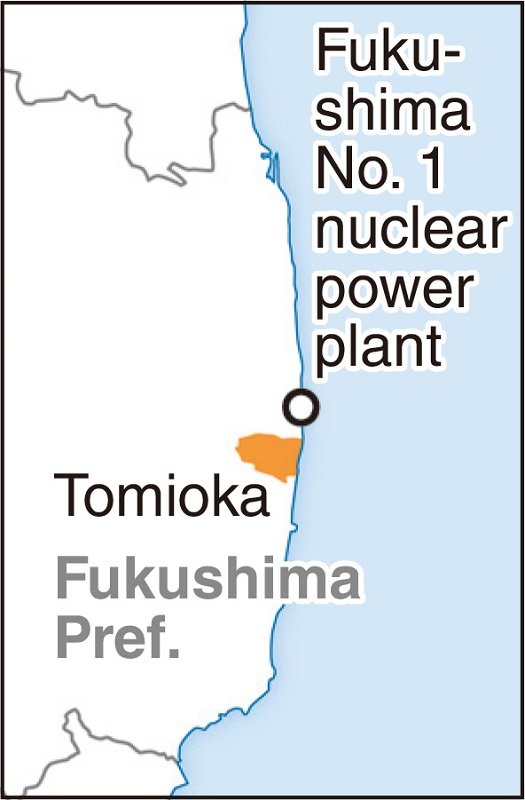

Ide, 22, is now living in the town for the first time since March 2011, when he and numerous others were evacuated after the Great East Japan Earthquake and the subsequent disaster at the nearby Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Ide will start work in April at a construction consulting company in Tomioka upon graduating from his university in Iwaki in the prefecture, about 35 kilometers to the south. When he told a professor at the university that he got a job in Tomioka and would be returning there, the professor asked, “Why would you go back if you don’t have to?”

He couldn’t find the words to explain it. What was clear to him was that he had been suddenly forced to leave the town on that day, and time there had stopped.

When the earthquake struck, Ide was a fifth grader at Tomioka No. 1 Elementary School. He lived with his parents and an older brother in a public apartment complex near the municipal baseball stadium, and was a member of a local baseball team. At a neighborhood park, he and his friends would spend all day pretending to be superheroes.

At 2:46 p.m. on March 11, his class was discussing the details of an upcoming school event when the shaking started. The massive tremor measured upper 6 on the Japanese seismic scale of 7, and the students were evacuated to the schoolyard still wearing their indoor shoes.

His grandfather came to get him and they headed straight to the grandfather’s house in the neighboring village of Kawauchi. The other members of the family also made it safely, only to learn on March 16 that the entire population of Kawauchi had to be evacuated because of the nuclear plant accident.

The family moved several times, staying at times at his maternal grandparents’ house in Iwaki and another relative’s house outside the prefecture. Ide spent his final year of elementary school in Hitachi, Ibaraki Prefecture.

Ide said he had no unpleasant memories of that school. He was the only evacuee from Fukushima Prefecture, and people there were considerate of his situation. But at times he felt sorry for getting special treatment.

Ide, far right, and elementary school friends pose for a photo in 2008.

Hearing classmates call each other by their nicknames would spur memories of friends back home. There was “Taka,” with whom he went to school every day, and “Eigo-kun,” a teammate on his baseball team. He didn’t even know if they were safe.

Seeing photos of himself from that time now, he notices there are none in which he appears cheerful.

Ide went to a municipal junior high school in Iwaki while living in temporary housing set up for evacuees. The first time he set foot in Tomioka following the disaster was during his third year, when he went with his mother by car for a quick visit.

Their apartment building had sunk into a crack in the ground, and the field where his baseball team practiced was piled high with black bags filled with topsoil removed during decontamination work. The Tomioka Station building remained in a state of ruin.

Forgetting his mother’s warning against possible radioactive exposure, he unconsciously got out of the car. He felt like he was lost in an unfamiliar town.

While in junior high school, he learned that a new high school, to be called Futaba Future School and run by the prefecture, would be built in Hirono, and would be accepting evacuated students living in Futaba county. The county covers two towns where the nuclear plant is located and other nearby municipalities, including Hirono and Tomioka. He chose to go to that school as he wanted a place that would make him feel closer to his hometown.

At the entrance ceremony for the school’s inaugural student body, he had an unexpected reunion. Also starting the new school was Shinya Niitsuma, a classmate in fifth grade at the Tomioka elementary school. He finally had a friend to share old memories.

The two talked about the large hotel run by a classmate’s family, the car dealership that would give them juice, the then Energy Museum at Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.’s Fukushima No. 2 nuclear power plant, where they could play video games for free. Anything and everything.

Ide got his driver’s license after starting university, and the two would drive together to Tomioka. They went to Yonomori Park, which they had visited on school excursions and is famous for its cherry blossoms. But entry was still restricted, and the two viewed the cherry blossoms in full bloom from a distance.

Walking around town, they were stunned to encounter wild boars roaming free.

“This is horrible, what do we do?” one said. “Who knows,” was the reply.

This spring, Niitsuma will start working in the Tomioka town office. Although they never talked about both working in the town, the friends share a strong connection with their hometown.

In early March, the two returned to look around the town again. Evacuation orders in most areas of the town had been lifted in April 2017, but the population was still only around 1,800. It was 16,000 before the earthquake.

They saw that an industrial zone had been developed along National Highway Route No. 6, and Tomioka Station had a new building. But an electronics retail store that had been scheduled to open in March 2011 still hadn’t, although its shop sign remained intact.

Their conversation reflected a feeling of loss, and a helplessness of getting it back.

“That Western restaurant that had the great hamburg steak, I wonder if it’s going to reopen.”

“Probably not.”

It will never be as it was. But they want to take the first steps forward.

Because it’s their town.

Most evacuees from Fukushima Pref.

The Reconstruction Agency put the number of evacuees nationwide from the Great East Japan Earthquake at 38,139 as of February. Of that total, 88%, or 33,402, were residents of Fukushima Prefecture.

In Futaba county, which comprises the eight municipalities of Hirono, Naraha, Tomioka, Okuma, Futaba, Namie, Kawauchi and Katsurao, only one in four residents actually live in the municipalities where they are officially registered.

Five of the eight municipalities have areas still designated as “difficult-to-return zones” due to high radiation levels. In a survey of their registered residents, few answered that they “have returned” or “want to return” to their municipalities.

Katsurao had the most responding in the affirmative at 48%, but the percentages were just 19% for Tomioka, 16% for Okuma, 11% for Futaba and 21% for Namie.

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged