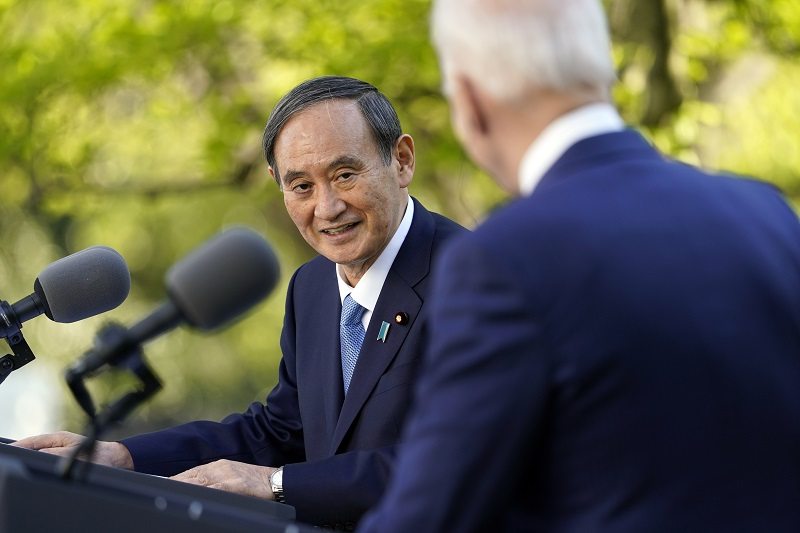

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga and U.S. President Joe Biden speak at a news conference at the White House in Washington on Friday.

17:05 JST, April 18, 2021

The latest summit between the Japanese and U.S. leaders was less pyrotechnics and more pragmatics, signaling a symbolic changing of the guard and setting the tone for a new chapter in Japan-U.S. relations.

Past pairings — whether of Shinzo Abe and Donald Trump, or Junichiro Koizumi and George W. Bush — were characterized by a strong-handed, top-down approach to policy, predicated on mutual trust cultivated between the leaders.

U.S. President Joe Biden chose Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga for his first face-to-face summit meeting not because he likes Suga, whom he has dubbed “Yoshi,” but because he has high expectations for the collective aptitude of Japan’s diplomatic team.

Unlike Trump, “Joe” respects the decisions made by his career diplomats. During the summit, both Suga and Biden presumably wanted to show that they know how to faithfully stick to the script.

Granted, the summit’s “success” was largely pre-orchestrated and widely expected following the earlier Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee, known as the 2-plus-2 security talks, which brought together the foreign and defense ministers of both countries.

The rise of China is the top foreign policy priority for the United States. Japan is situated next to China, so its importance as a strategic ally should continue to grow going forward.

But for both Japan and the United States, the hard part is yet to come.

The United States’ hopes for Japan are motivated by Washington’s awareness of its limited ability to face China on its own. If Biden is perceived to be weaker on China than Trump, he will inevitably face a pushback in public opinion.

Should the 78-year-old Biden fail to produce results by the time of the U.S. midterm elections in autumn next year, he risks losing momentum and being written off as a one-term president. Such considerations may explain why the new U.S. administration, which conventionally takes several months to get around to sinking its teeth into foreign policy, has been moving faster than the Japanese government had anticipated.

This eagerness to hit the ground running has also invited a sense of apprehension on the Japanese side, given how many U.S. high-ranking diplomacy and security posts are occupied by appointees who have yet to be confirmed by Congress.

The show of solidarity as Tokyo and Washington stood shoulder to shoulder and called out China by name, issuing their first joint statement in half a century that addresses the Taiwan situation in unambiguous terms, may conversely work to escalate tensions, and provoke greater blowback from China.

It would be wise for Japan to not merely follow the pace dictated by the United States, but also to prepare its own contingency plans, in the event that the U.S. government decides to veer off course or adjust its timetable on China.

The Suga administration appears to have plenty of homework to do after the summit.

In the event of a Taiwan contingency, Japan needs to be ready to offer explanations to the public, as well as the U.S. government, regarding whether the situation is deemed to “have an important influence,” which would allow the Self-Defense Forces to provide logistic support, or threatens Japan’s survival in a way that would justify exercising the nation’s right to collective self-defense in a limited manner.

The issues that Japan and the United States will need to tackle have now been well laid out. The overall strength and teamwork of each administration is what will count in this new test, rather than the compatibility of the two leaders.

"Politics" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

Japan, India Aim for More Than 500,000 People-to People Exchanges over Next 5 Years

-

Chief of Japan’s SDF Logistics Unit in Djibouti Vows to Assist Japanese Nationals in Emergencies, Stresses Need to Prepare for Protecting Citizens

-

Govt Expert Panel’s Report Recommends Exporting Defense Equipment ‘Without Restrictions’

-

Ruling, Opposition Parties Deepening Confrontation over Economic Policies after PM Ishiba Announces He Will Step Down

-

Ishiba Again Says He will Remain Prime Minister, with Criticism from LDP Lawmakers Mounting over His ‘Clinging to Power’

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan’s Real Wages, Consumer Spending Climb but Inflation Challenges Persist

-

China’s Youth Unemployment Remains High at Over 17% in July Amid Serious Job Market Recession

-

Japan in Prime Spot for Total Lunar Eclipse Early Monday Morning, 1st Visible from Country in Almost 3 Years

-

Japan, India Aim for More Than 500,000 People-to People Exchanges over Next 5 Years

-

S. Korea’s Lee Eager to Enhance Ties with Japan More