The World’s Greatest Mathematician Avoided Politics. Then Trump Cut Science Funding.

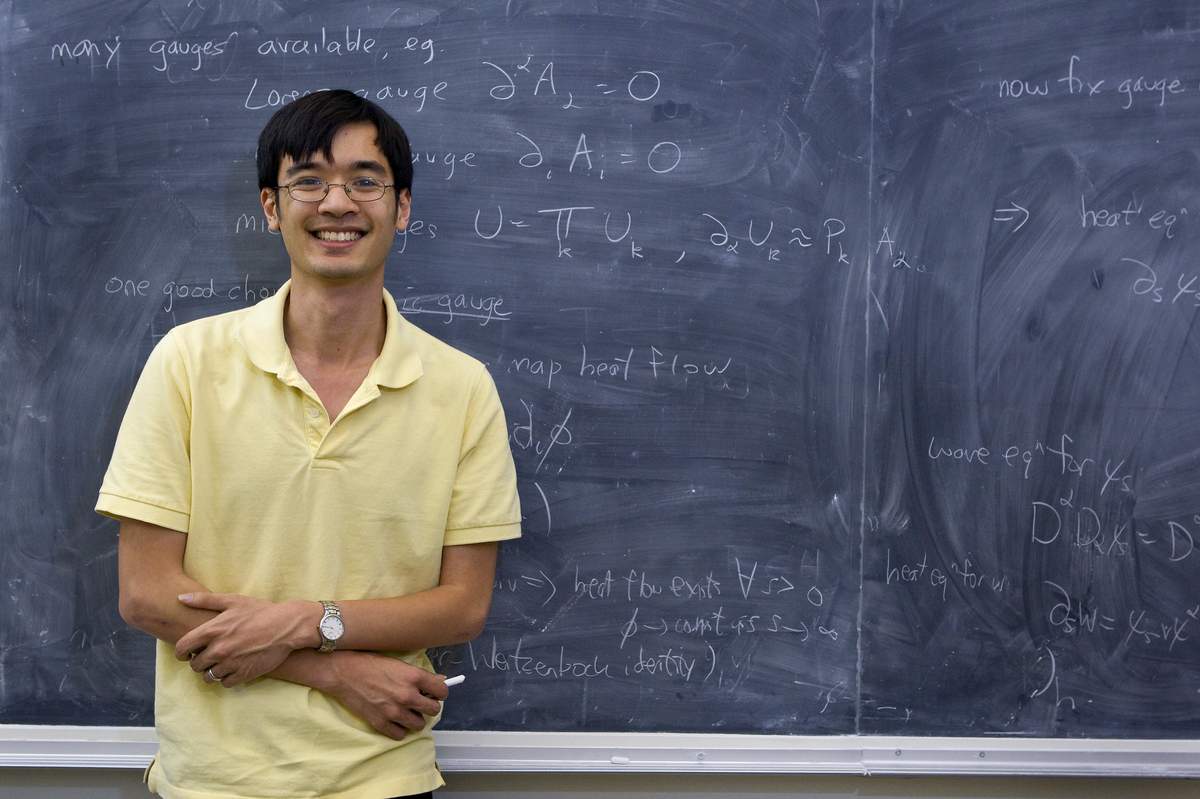

Tao, often called the “Mozart of Math,” was born in Australia but built his career in the United States, saying the scientific culture encouraged researchers to think big.

12:20 JST, September 8, 2025

Terence Tao is often called the “Mozart of Math.” A child prodigy born in Australia, Tao, 50, is now at the top of his field at the University of California at Los Angeles, working in the rarefied realms of partial differential equations or harmonic analysis on problems so hard it may take a PhD to understand them. But for the past few weeks, he’s been preoccupied with more run-of-the-mill pecuniary concerns: fundraising.

Being one of the world’s greatest mathematicians didn’t protect Tao from losing his National Science Foundation grant in late July, when the Trump administration froze about half a billion dollars in federal research funding after accusing UCLA of mishandling antisemitism and bias on campus.

A court order restored National Science Foundation grants, including Tao’s. But no new awards can be made, putting at risk the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics (IPAM), where he is director of special projects. Tao works in esoteric realms, which can lead to tangible real world benefits. For example, some of his work at IPAM has helped make MRI scans faster.

Math is often portrayed as a largely inscrutable pursuit by lone geniuses, but Tao is a hero to many mathematicians, known for the breadth of his interests and his engagement with the public. On social media, he has shared the fact that his papers get rejected from journals – even certified geniuses can have impostor syndrome.

Math and politics don’t often intersect, but Tao is speaking out about how upheavals, delays and uncertainty in federal funding imperil the unique American ecosystem for science. He spoke to The Post about the events of the last few weeks, the appeal of doing research in the United States and why math matters. This interviewed has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Q: What happened to your current grant?

A: I got an email from a journalist from the Bulwark. He first told me that my grant had been suspended and … then he also mentioned casually that the IPAM, the math institute here also got defunded. And that’s a grant that’s 40 times bigger than my own. And much, much more serious. Suddenly, we didn’t have the operating funds to run for three months.

Because of previous delays in funding, I didn’t have enough money to fund my own summer salary. I was already delaying that for one month. And so, yeah, it’s still delayed, but that’s fine. I can take it. But IPAM, they didn’t have the reserves to operate for more than a few months. So basically, for the past two weeks or so, we’ve been in an emergency fundraising mode. I’ve been meeting with lots of donors.

Q: A lot of people that I’ve been speaking to, researchers in different fields, have said that they’ll be okay because they’re more senior. But they’ve expressed a lot of concern about early career researchers and scientists.

A: The NSF grant that I had, I mean its primary purpose was to support my graduate students, give them the opportunity to travel to a conference, which is really important for career development at that stage, to buy them out of teaching for one quarter so that they can work on research. And, you know, at that career level, having a paycheck for $3,000 really makes a difference.

Q: You didn’t grow up in the United States. Why did you choose to build your career here?

A: I myself had no strong desire to leave Australia, and I was also 16 at the time – I wasn’t really thinking about geopolitics or anything. … The adviser I ended up studying under at Princeton was actually the one who wrote one of the most influential textbooks for me as an undergraduate. I distinctly remember the experience of going into Princeton’s math department the first time and looking at the list of professors and recognizing the names of people I’d read about in books.

The U.S. has always had a strong scientific reputation, at least in my lifetime. It’s just the sheer scale of activity and just the general support for science, until recently very bipartisan – an understanding that science brings prosperity, it helps national security. And it’s just a public good. There’s a very positive culture here. People are really sort of ambitious and big thinking and collaborative, and they want to build something that lasts.

Q: If you’ve spent the past few weeks fundraising rather than doing research, what would you normally have been doing?

A: The thing I’m most interested in right now is finding ways to use all these new modern computer technologies. AI most famously, but there are other things called formal proof assistants and collaborative platforms like GitHub … to try to reinvent the way we do mathematics.

Mathematicians, traditionally, we work alone or in small groups of like three or four people. We work with pen and paper quite often. … Compared to the other sciences, we’re still very old school … I’m hoping to organize some experimental projects where we take a big math problem, we break it up into little pieces and then we try to crowdsource some pieces. And maybe some pieces we leave to professionals, and then try to use all this modern software to coordinate and check all the contributions – and do “big math” the way that other sciences have begun to do “big science.” We have no analogue of the human genome project or the Higgs boson experiment. We are still stuck in the early 20th century or earlier.

Q: Most people’s experience of math is a much lower level than you are at. What’s it like to discover something in math?

A: Math is, to me, is about making connections between things you didn’t know were connected.

I worked at IPAM actually 20 years ago on this problem of image processing. Like you have an MRI scanner, you’re scanning a human body and it receives a certain amount of data. You want to reconstruct a high quality resolution image of the human body so that you can detect tumors.

It turns out that there’s these very old math puzzles called “coin weighing puzzles,” where you have 12 coins, they’re all the same except that one coin is counterfeit, either too heavy or too light. And you have a balance scale, so you can put coins on one side and coins on the other and see which one’s heavier or lighter. And your task is to use the scale to identify which coin is the counterfeit coin, but the catch is that you’re only allowed to use it three times.

It turns out that the mathematics of solving these coin-weighing puzzles and the mathematics of extracting a high quality image from a very few measurements is actually a very similar problem, even though their sources are very different. So once you translate them to math, you can see the similarities and then you can use ideas used to solve these puzzles to help solve these MRI scans. In fact, because of the work I did at IPAM 20 years ago and the contributions of many, many other people, the most modern MRI machines … actually incorporate our algorithms, which have sped up MRI scans by almost a factor of 10.

Q: Some tech leaders have argued that human scientists will become irrelevant because AI will be so capable to do science. What do you think of that argument?

A: Well, it will transform science. The same way computers have transformed science in the past. A lot of our time, a scientist’s time, is taken up with rather tedious things. So 120 years ago, mathematicians would spend a lot of time just doing computations by hand, just numerical sums, because they had no choice. But because of computers, you can off-load that part of doing mathematics to the machine, and then you spend your time doing other things.

Genetics is a good example. To sequence a single organism was an entire PhD project. But now you can send it to a sequencer and pay a thousand dollars or something. You can get a complete sequence of an organism. This doesn’t mean that PhDs in genetics have become obsolete. It means that these PhD students are doing more ambitious things.

Q: A lot of what’s happened at institutions over the last seven months, not just UCLA, is slowdowns and uncertainty and then sometimes reversals so that the effects are often somewhat temporary. If things do go back to normal, why does the uncertainty make a difference?

A: Because so much of it just was planning and budgeting and also just mental. In order to do the best science, you also need to have a somewhat tranquil mental state. Just to give it an analogy, suppose it’s a little bit chilly. It’s 60 degrees in your home, and so you set your heater to 72. But suppose that your thermostat suddenly changes the temperature to 100 degrees and then to 40 degrees and finally it’s back to 72 degrees. On paper, you now have the right temperature, but you’re not feeling too good after this. And somehow you can’t relax and sort of be productive, especially if you are worried that it’s going to do that again. A lot of what the federal government [has done in the past] is actually just providing stability and predictability. This has always been a great strength of the U.S.

Q: Do you have a sense of optimism or would you ever consider leaving the U.S.?

A: I’ve had a very positive experience at the U.S. for 30 odd years … It offers so many things that are definitely not perfect, but you feel like things can happen here, really good things.

Now there’s uncertainty and, you know, 12 months ago, [if] you asked me, am I going to leave it? It was not on my radar at all. Now, I would very much like to stay and for things to get back to something resembling normal. What’s hardest to restore is the sense of predictability and stability.

People who support all the positive aspects of America have to speak out and fight for them now. The things that you took for granted, there was bipartisan support to keep certain things in the U.S. running as they have been more or less for the past 70 years because the system worked. That’s not a safe assumption anymore.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza