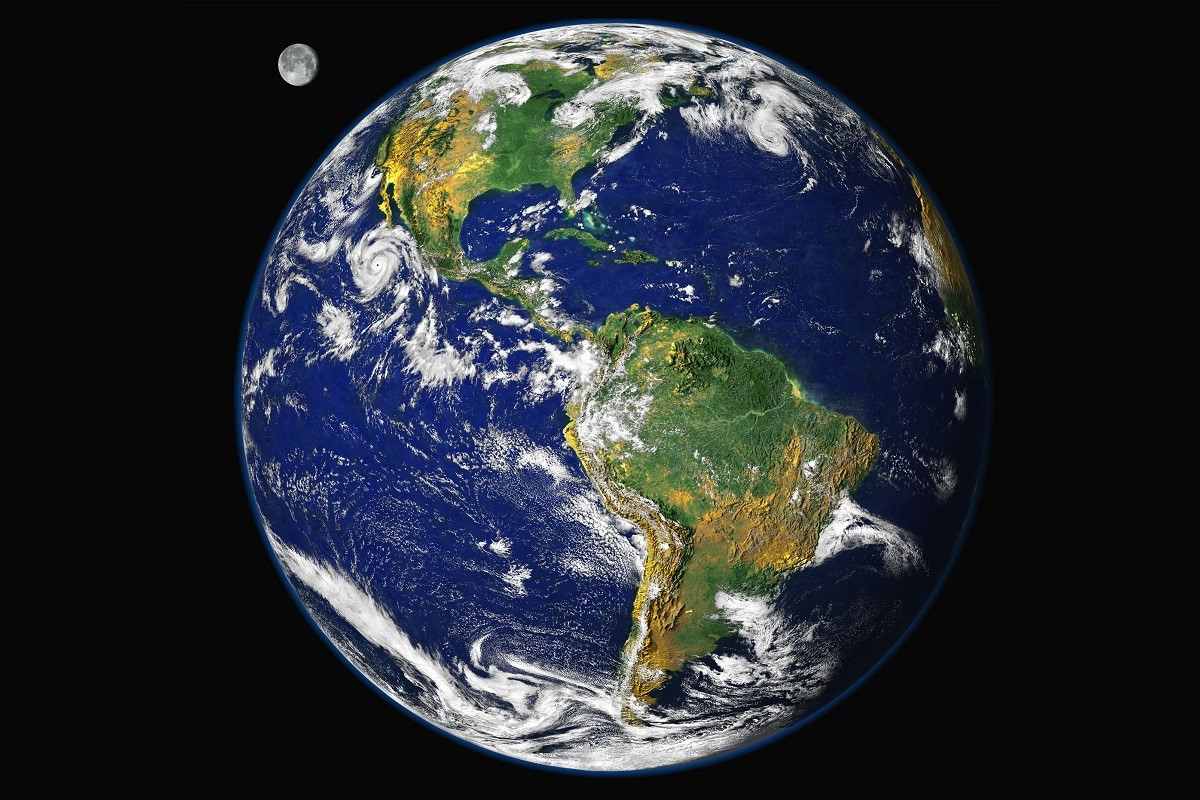

To mark Earth Day on April 22, NASA scientists have released this new image of the Earth, updating the famous “Blue Marble” photograph taken by Apollo astronauts.

16:16 JST, March 26, 2023

When Sean Youra was 26 years old and working as an engineer, he started watching documentaries about climate change. Youra, who was struggling with depression and the loss of a family member, was horrified by what he learned about melting ice and rising extreme weather. He started spending hours on YouTube, watching videos made by fringe scientists who warned that the world was teetering on the edge of societal collapse – or even near-term human extinction. Youra started telling his friends and family that he was convinced that climate change couldn’t be stopped, and humanity was doomed.

In short, he says, he became a climate “doomer.”

“It all compounded and just led me down a very dark path,” he said. “I became very detached and felt like giving up on everything.”

That grim view of the planet’s future is becoming more common. Influenced by a barrage of grim U.N. reports – such as the one published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change earlier this week – and negative headlines, a group of people believe that the climate problem cannot, or will not, be solved in time to prevent all-out societal collapse. They are known, colloquially, as climate “doomers.” And some scientists and experts worry that their defeatism – which could undermine efforts to take action – may be just as dangerous as climate denial.

“It’s fair to say that recently many of us climate scientists have spent more time arguing with the doomers than with the deniers,” said Zeke Hausfather, a contributing author to the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and climate research lead at the payments company Stripe.

There are different flavors of doomers. Some are middle-aged and have been influenced by outspoken scientists – like retired ecologist Guy McPherson – who claim that human extinction, or at least the breakdown of society, is imminent. (“I can’t imagine that there will be a human left on the Earth in 10 years,” McPherson has said.) These doomers drift toward conspiracy theories, sometimes claiming that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is downplaying the seriousness of the issue.

McPherson said in an email that while he’s “no fan of extinction … so called ‘green energy’ based on PV solar panels and wind turbines offers no way out of the ongoing climate emergency.”

Others are young people, active on social media, who have become demoralized by years of negative headlines. “Since about 2019, I have believed that there is little to nothing we can do to reverse climate change on a global scale,” Charles McBryde, a TikToker, said in a video last year.

The origins of doomism stretch back far – McPherson, for example, has been predicting the demise of human civilization for decades – but the mind-set seems to have become markedly more mainstream in the past five years. Jacquelyn Gill, a climate scientist at the University of Maine, says that in 2018 she started hearing different sorts of questions when she spoke at panels or did events online. “I started getting emails from people saying: ‘I’m a young person. Is there even a point in going to college? Will I ever be able to grow up and have kids?'” she said.

Well before the coronavirus pandemic, a few factors combined to make 2018 feel like the year of doom. 2015, 2016 and 2017 had just been the three hottest years on record. Climate protests had begun to spread across the globe, including Greta Thunberg’s School Strike and the U.K.-based protest group known as Extinction Rebellion. In the academic world, British professor of sustainability Jem Bendell wrote a paper called “Deep Adaptation,” which urged readers to prepare for “inevitable near-term societal collapse due to climate change.” (The paper has been widely critiqued by many climate scientists.)

And then the United Nations issued a special report on 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming, released in October 2018, which kicked many people’s climate anxiety into overdrive.

The report, which focused on how an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius from preindustrial levels might compare to 2 degrees Celsius, included grim predictions like the death of the world’s coral reefs and ice-free summers in the Arctic. But a central message many took from the report – that there were only 12 years left to save the planet – wasn’t even in the report. It came from a Guardian headline.

In three of the four pathways the report charted for limiting warming to 1.5C, the world would have to cut carbon dioxide emissions 40 to 60 percent by 2030. “We have 12 years to limit climate catastrophe,” the Guardian reported, and other outlets soon followed. The phrase soon became an activist rallying cry.

“‘Twelve years to save the planet’ was actually: We have 12 years to cut global emissions in half to stay consistent with a 1.5C scenario,” Hausfather explained. “Then ’12 years to save the planet’ becomes interpreted by the public as: If we don’t stop climate change in 12 years, something catastrophic happens.”

“It was really a game of telephone,” he added.

Hausfather said part of the problem is that climate targets – say, the goal to limit warming to 1.5C – have become interpreted by the public as climate thresholds, which would drive the planet into a “hothouse” state. In fact, scientists don’t believe there is anything unique about that temperature that will cause runaway tipping points; the landmark IPCC report merely aimed to show the risks of bad impacts are much higher at 2C than at 1.5.

“It’s not like 1.9C is not an existential risk and 2.1C is,” Hausfather said. “It’s more that we’re playing Russian roulette with the climate.” Every increase in temperature, that is, makes the risks of bad impacts that much higher.

Still, scientists who try to clarify those nuances sometimes encounter hostility, particularly online. “If you try to push back on this in any way, you get accused of minimizing the climate crisis,” Gill said. “I’ve been accused of being a shill for the fossil fuel industry.”

The problem with climate “doom” – beyond the toll that it can create on mental health – is that it can cause paralysis. Psychologists have long believed that some amount of hope, combined with a belief that personal actions can make a difference, can keep people engaged on climate change. But, according to a study by researchers at Yale and Colorado State universities, “many Americans who accept that global warming is happening cannot express specific reasons to be hopeful.”

And it’s not just Americans. Andrew Smith, a retired engineer from Yorkshire, England, is slightly turned off by the term “doomer.” It provokes, he says, a sense of being on the fringes of society, or visions of doomsday preppers filling their bunkers with canned food. “For me, a climate doomer is simply a person who’s taken a look at the peer-reviewed science, taken stock of the natural world around them, and come to a conclusion,” he wrote in a message via Twitter. Smith believes that the world is on track to warm 4 to 8 degrees Celsius compared to preindustrial times.

For some, however, doomism isn’t permanent. Youra, the former engineer, still remembers how strongly he felt that humanity was done for. He believed that the IPCC and other scientists were covering up how bad climate change actually was – and no peer-reviewed research could convince him otherwise. “I think it’s kind of similar to what deniers feel,” he said. “I wasn’t being open-minded.”

In 2018, he briefly considered quitting his job to travel the world – hoping to see what he could before society and the natural world collapsed. Slowly, though, he started getting involved in local climate groups, and when he attended a meeting in Alameda for the California city’s climate plan, something clicked. “I think that for me was key,” he said. “It made me start realizing the power of good policy.” Now 32, he has earned a master’s degree in environmental science and policy and works as the climate action coordinator for the California towns of San Anselmo and Fairfax.

Worry – and even occasional despair – about the climate crisis is normal. Most scientists believe that, without deeper cuts, the world is headed for 2 to 3 degrees Celsius of global warming. But higher temperatures are still possible if humans get unlucky with how the planet responds to higher CO2 levels. Kate Marvel, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute, has said that while humans probably won’t go extinct due to climate change, “not going extinct” is a low bar.

“It’s a question of risk, not known catastrophe,” Hausfather said.

But finding the balance between constructive worry – that is, concern that motivates you to do something – and a sort of fatalistic doom is difficult. Nowadays, climate scientists try to emphasize that climate change isn’t a pass/fail test: Every tenth and hundredth of a degree of warming avoided matters.

For his part, Youra has advice for those who are suffering from the same sort of fatalism that he once felt. “Stop engaging excessively with negative climate change content online and start engaging in your community,” he said. “You can be one of those voices showing there is support for the solutions.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza