The then Imperial Diet passed a bill to revise the Constitution in 1946, and it came into effect in 1947.

8:00 JST, April 8, 2023

The original manuscript of the Constitution of Japan is kept in the National Archives, near the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. The paper is aged, and the words themselves are written in the old-style Japanese that was in use more than 70 years ago. Not a single word of the Constitution has been changed since it came into effect in 1947, two years after the end of World War II.

This does not mean the Constitution is considered perfect, or that there is nothing to amend. Nor does it mean that constitutional issues have not played a significant role in Japanese politics. Quite to the contrary, Article 9, which prohibits the use of force and the maintenance of armed forces, has been the most contentious issue between the ruling and opposition parties.

In the last several months, opposition party members and Cabinet ministers have argued over the constitutionality of same-sex marriage, which in the government’s view is not allowed under the Constitution, and defense policy issues such as whether to possess “counterstrike” capabilities to attack enemy missile bases.

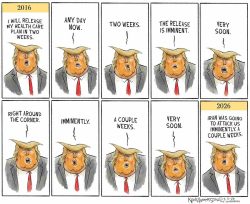

The long-dominant ruling Liberal Democratic Party has included constitutional revision as a plank in its party platform for a long time, but many LDP presidents who became prime minister said they had no intention of tackling constitutional change. They all knew that amending the Constitution was barely possible because of the lengthy and complicated procedures required.

As stated in the Constitution itself, a draft revision needs to pass both houses of the Diet by a majority of at least two-thirds and then must be approved by the people in a national referendum. The LDP alone has never won such a majority in both houses at the same time. As their coalition partner Komeito has hesitated to change the Constitution, it has been hard to reach the required majority in the Diet.

Winning public understanding and support and achieving overwhelming majorities in both houses are only part of what is needed to realize a revision of the Constitution. It is also necessary for a prime minister — presumably one who heads the LDP — to be resolutely determined to bring it about, and to have no political scandals or other great challenges to create friction. Because those who advocate protecting the Constitution as it is oppose amendments very strongly, the prime minister, the cabinet and the LDP need to absorb severe political headwinds.

Shinzo Abe, who was shot dead last year, was the only prime minister who put the revision of the Constitution on his political agenda and tried to surmount these difficulties. He was known as a leader of the pro-amendment camp in the LDP. After he took office for the second time in 2012, he tried to change the amendment procedure by attempting to lower the requirement of a two-thirds majority. He had to give up that plan when he was criticized for trying to “slip in through the back door.”

Then Abe advocated for revising Article 9, which has been the core issue regarding constitutional change. His idea was to clearly stipulate the existence of the Self-Defense Forces to make them constitutional. Nevertheless, he could not achieve a consensus within his administration over how to revise the article. In the latter half of his term, his campaign for constitutional reform lost momentum owing to his political scandals and the COVID-19 pandemic. Even Abe, the longest-serving prime minister and one who had enjoyed significant popularity, could not get the amendment procedure started.

If you trace Japan’s prewar political history, you will find that the Empire of Japan also never revised its Constitution. The government at the time claimed their Constitution was untouchable forever. The devastating defeat in the war and occupation under the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces led by U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur made possible a sweeping revision, formulating a whole new democratic Constitution.

But the case of Japan differs greatly from those of other countries. According to research by the National Diet Library, the Constitution of the United States has been amended six times since the war. France has revised its Constitution about 30 times, including the creation of a new one, and the German Basic Law has been revised more than 60 times.

The problem is that Japan has stuck to an “unchangeable” Constitution and can’t correct its flaws or insufficiencies. These flaws and insufficiencies include a lack of articles — which other countries have — regarding states of emergency. Owing to the ambiguity over security policy, some constitutional scholars even deny the nation the right to self-defense, a situation quite unique to Japan.

The Japanese government has repeatedly modified its constitutional interpretations to adapt to changing situations by means other than revising the Constitution itself. But these efforts have definite limitations and have caused a loss of hope that Japanese politics will dramatically respond to changing needs.

More than 60% of Japanese voters were in favor of revising the Constitution in a Yomiuri Shimbun poll last year. This was the highest figure in recent years. They supported new provisions on issues including the recognition of armed forces for self-defense, emergency measures and free education. The Japanese people may have a sense of the limitations of an untouched Constitution, but there are so many high bars for revising the Constitution that it is unlikely that they will participate in a national referendum on amendments anytime in the near future.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Takayuki Tanaka

Tanaka is senior managing director, chief officer, administration, of The Yomiuri Shimbun. His previous post was managing editor.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

Flu Cases Surging Again: Infection Can Also Be Prevented by Humidifying Indoor Spaces

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan