Picture books symbolize Japan’s modern history / Critic tracks, examines transition through 100 selected works by 100 artists

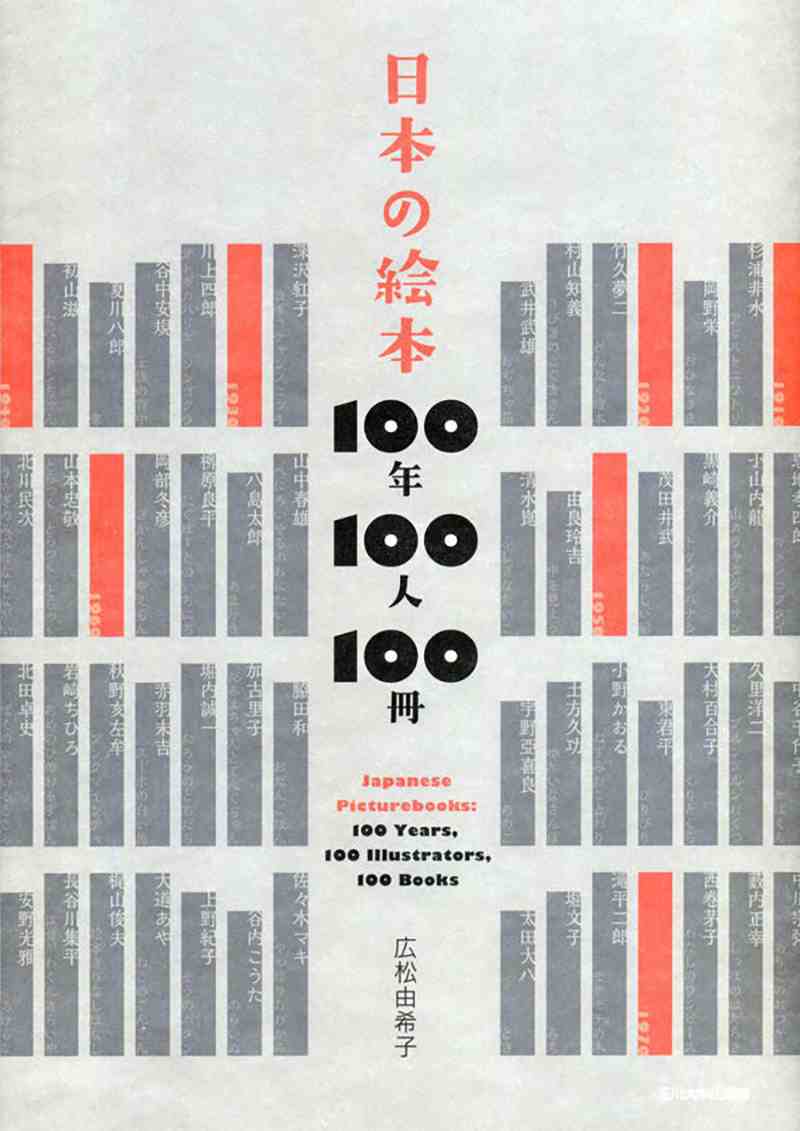

“Japanese Picturebooks: 100 Years, 100 Illustrators, 100 Books”

11:37 JST, March 3, 2022

A newly published book sheds light on the modern history of Japanese picture books, chronologically featuring 100 selected works printed in the past century along with many illustrations and information about their creators.

Titled “Nihon no Ehon Hyakunen Hyakunin Hyakusatsu” (“Japanese Picturebooks: 100 Years, 100 Illustrators, 100 Books”) and published by Tamagawa University Press, the book was authored by Yukiko Hiromatsu, a picture book critic. Hiromatsu herself stor and exhibition planner of picture books, having previously worked as a picture book editor and as the chief curator at Chihiro Art Museum. She also has served as a judge for international picture book elected the 100 works.

The author is also active as a translator and exhibition planner of picture books, having previously worked as a picture book editor and as the chief curator at Chihiro Art Museum. She also has served as a judge for international picture book competitions.

Hiromatsu believes that Japan is one of the world’s “picture book nations,” with many works that have sold well for more than half a century and numerous new books being published each year. Unfortunately, Japan does not actively promote its picture books globally, resulting in many works having no international recognition. “I want to tell many people that Japanese picture books are very interesting,” Hiromatsu said. “I thought I might be able to offer something significant by presenting picture books along a horizontal axis representing world affairs and a vertical axis representing the passing of time.”

In the book, she chronologically features 100 books, each by a different illustrator or group of illustrators.

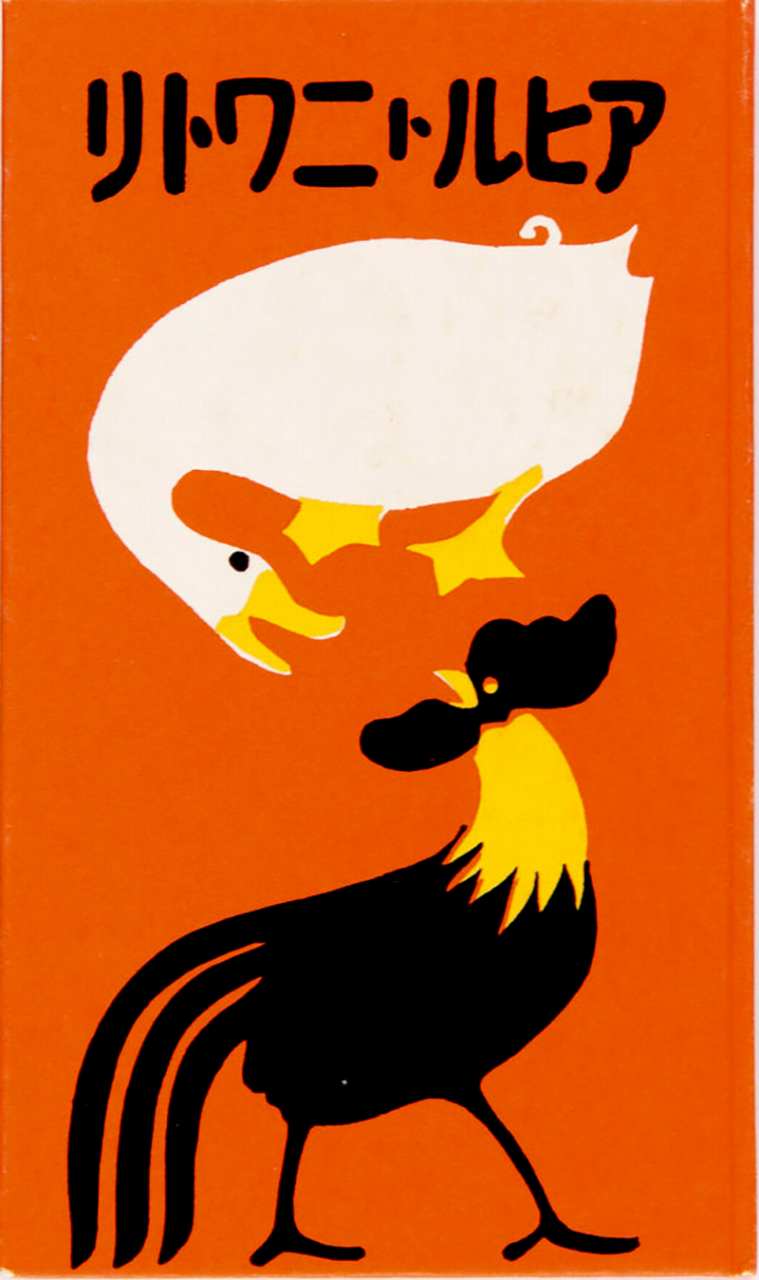

The first book is “Ahiru to Niwatori” (Ducks and chickens, 1912) with illustrations by Hisui Sugiura. This book is included in the Nippon Ichi no Ebanashi series (A series of the best illustrated books of Japan) published by the Nakanishiya Shoten.

The stories in the series were written by renowned author Sazanami Iwaya and the illustrations were created by three students of acclaimed painter Seiki Kuroda, including Sugiura. The illustrations in the book have black silhouettes set against monochrome backdrops, creating a sharp contrast.

“Ahiru to Niwatori” illustrated by Hisui Sugiura

Some of the 100 books show the playful spirit of their creators, such as “Omochabako” (Toy box, 1927) by Takeo Takei, who is said to have coined the term “doga” (paintings and illustrations associated with children’s literature and culture) to define them as a field of art.

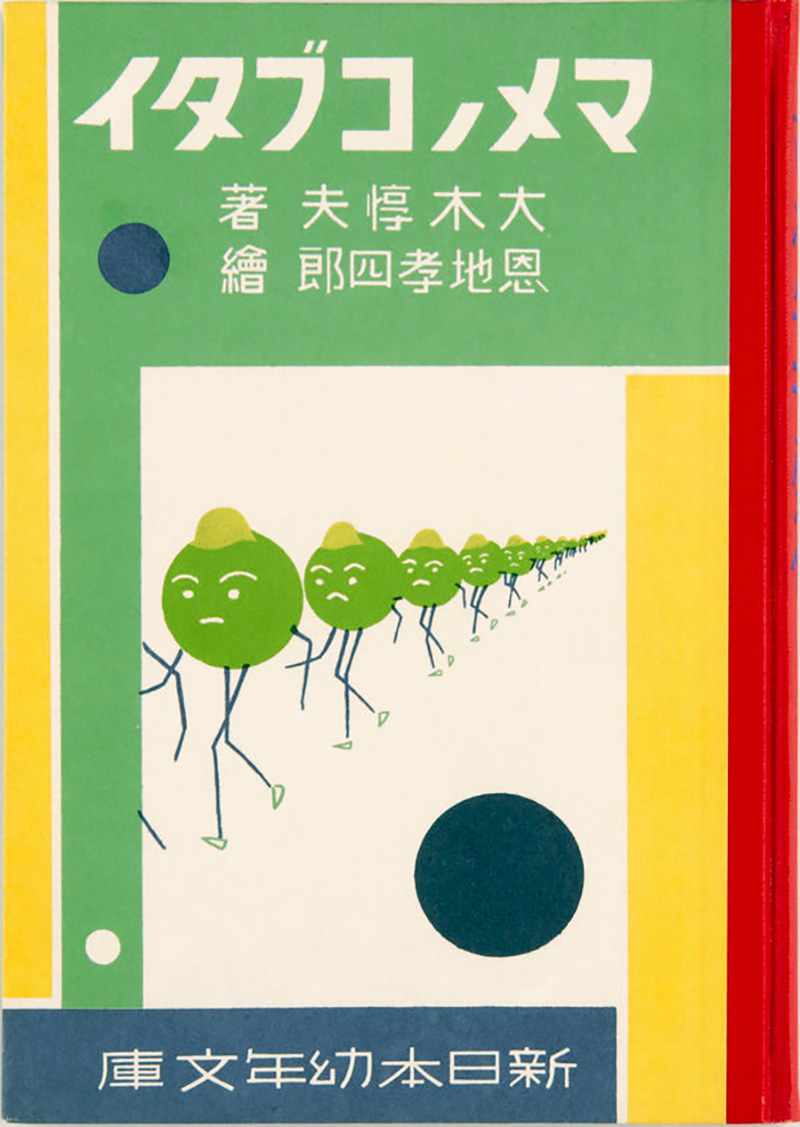

As war spread in the 1930s and early 1940s, some books were written to increase children’s enthusiasm for fighting, such as “Mamenoko Butai” (Pea troops, 1941) illustrated by Koshiro Onchi, which uses peas as stand-ins for human brothers going to war.

“Mamenoko Butai” illustrated by Koshiro Onchi

Hiromatsu said, “Publication was controlled by the authorities in wartime. We must not allow this to happen again. Also, we should not forget that [there were adults who] made efforts to give beautiful things to children even in that difficult situation.”

The three works mentioned above were later reprinted by Holp Shuppan Publications.

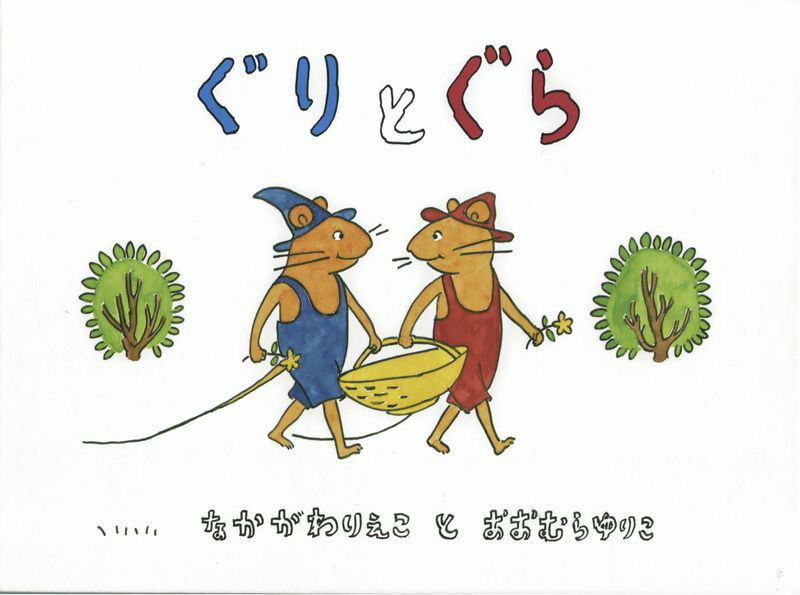

After World War II, picture books based on the new values of freedom and democracy were published one after another, giving rise to a “golden age” in the 1960s and 1970s. Many books published around this time continue to attract new readers, including “Guri to Gura” (Guri and Gura: The Giant Egg, 1963) by Yuriko Omura, “Darumachan to Tenguchan” (Little Daruma and Little Tengu, 1967) by Satoshi Kako, and “Moko Mokomoko” (1977) by Sadamasa Motonaga.

“Guri to Gura” illustrated by Yuriko Omura

The 100th book is “Ore to Kiiro” (Yellow and I, 2014) by Mirocomachiko. Described by Hiromatsu as “a work symbolizing the modern era after the Great East Japan Earthquake,” it features a blue cat named Ore that chases after Kiiro, a mysterious yellow mass that feels like the source of life.

Hiromatsu said, “After the earthquake, we were forced to think about what hope we can give to children. Artists also searched for what to express and how. This book gives us the vitality that we have wanted to wake up our bodies.”

Yukiko Hiromatsu

“All of the books are worth reading many times throughout one’s life,” Hiromatsu said confidently. She selected all the books from her own bookshelf based on her own taste. For example, when selecting a book by Yoko Sano, Hiromatsu chose “Umaretekita Kodomo” (A child who has been born, 1990), rather than “Hyakumankai Ikita Neko” (The Cat That Lived a Million Times), for which Sano is better known.

“I recommend that people compare works that they would choose with the works featured in my book and make their own booklist as an opportunity to talk about picture books with other people,” Hiromatsu said.

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan