Nobody Left Behind: Individual Evacuation Plans for Vulnerable Residents Key to Everyone Escaping in Disasters

17:59 JST, July 22, 2025

Individual evacuation plans are arrangements made in advance for the elderly, the disabled and other people with special needs who have difficulty evacuating in a disaster. The plans determine who should help them, where they should find shelter and which route they should take when evacuating.

When the Basic Law on Disaster Management was revised in 2021, the local governments of every city, town and village nationwide became obliged to make their best efforts to draw up such plans, which are being drafted all over the country. This is a report on the background to the amendment, and what is actually happening with the making of the plans.

The evacuation of vulnerable people in times of disaster emerged as a major problem after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Since many people failed to escape and became victims of the tsunami, in 2013 the central government made it mandatory for all local governments to make lists of residents who would need assistance in an evacuation. The government also designed a system to let local disaster prevention groups access information about the people on the lists with their consent.

However, when torrential rain hit the western part of Japan in 2018, many elderly people were unable to escape. They accounted for about 70% to 80% of fatalities.

Therefore, the 2021 revision to the law introduced a framework for people who need assistance in a disaster. This framework includes making an evacuation plan for each of vulnerable resident — who they should evacuate with, where they should evacuate to and how they should evacuate — and sharing the information with the person in question, their local government and the local community.

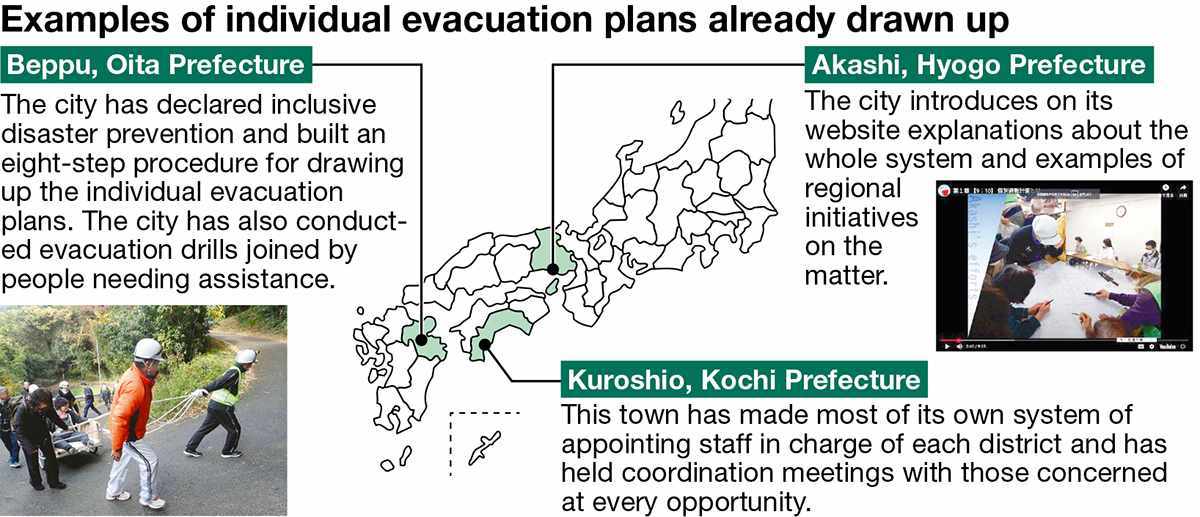

Eligibility and how the plans are formulated vary from municipality to municipality. The plans are often made by personnel specializing in welfare issues.

In Higashi-Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, the plan for each individual is made by their care worker after discussions with the person and their family. In the case of a mobility-impaired woman in her 70s who lives on her own in an area of the city subject to landslide disaster warnings, her care worker’s network proved very useful. The designated shelter the woman was supposed to evacuate to was about 500 meters away from her house, which was too far for her. Her care worker sought advice from an acquaintance whom she got to know through care work communities. The acquaintance happened to live in an apartment close to the woman’s house and agreed to give her temporary shelter in an emergency. The woman will evacuate to the apartment in the event that the city warns the elderly to evacuate.

The municipal government of Beppu, Oita Prefecture, has collaborated with private-sector organizations supporting people with disabilities, and together they have decided on an eight-step evacuation procedure. This includes checking on the situation of each vulnerable person as well as running evacuation drills and amending the plans. The procedure has been drawing attention as the “Beppu model.”

“Making [individual evacuation] plans shouldn’t be the sole goal. The important thing is the process of preparing the environment for evacuation, working together with local communities,” said an official at the municipal government’s policy planning department.

One problem is that the pace of drawing up the plans varies from municipality to municipality. Local governments were supposed to complete the task about five years. As of April 2024, however, local governments that had completed more than 80% of their plans accounted for about 14% of all municipalities. About 8% of them have not yet completed any plan.

The central government is offering support to local governments by subsidizing the expenses for the plans at a level of about ¥7,000 per person and by holding debriefing meetings with local governments that have already completed the task.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan