Xue Yang, 28, posts photos of lunches she ate over the course of nine days, including steamed rice, two hot dishes and some homemade drinks.

13:15 JST, December 2, 2024

Call it under-consumption core. Call it frugality. In China, call it “proudly stingy.”

Just as the cost of living is weighing on many Americans – and even helped propel Donald Trump back into the White House – so too are many Chinese worrying about making ends meet, even while Chinese food costs are a fraction of American ones.

As the world’s second largest economy slows and the job market dries up, tens of thousands of young Chinese are embarking on money-saving challenges and sharing their latest feats on social media. One trend that has taken off in recent months: spending no more than $70 a month, or 500 yuan in Chinese currency, on feeding themselves.

Participants upload photos of what they eat each day and detail the costs of each item on the popular platform Xiaohongshu, which has at least 300 million active users. Some who finish a month with money to spare go on to target an even a lower budget.

Some say their quality of life has not dropped substantially.

The current trend toward buying less and saving more stands in stark contrast with the conspicuous consumption of recent years, when deep-pocketed, big-spending Chinese nouveau riche showed off their sports cars, premium watches and designer bags.

Louis Vuitton owner LVMH, the world’s largest luxury goods company, reported last month that its sales of fashion and leather goods dropped for the first time since the pandemic amid a slump of demand in the Chinese market.

Now, it’s penny-pinching and eating in that’s resonating with many middle class Chinese, as widespread pessimism over the economic outlook and job market spreads.

This is how some Chinese millennials are feeding themselves.

Changing priorities after a job loss

Xue chose a vacation close to home instead of international travel, as a way to save money.

Xue Yang, a 28-year-old woman in Shanghai, had a well-paid job as a financial adviser at a computer-software company until the end of last year. She bought an apartment with her husband, spent generously on travel and clothes, and never thought of tracking daily expenses. Then her company, struggling amid an industry-wide recession, let her go.

Living on severance pay and savings, she took a few months off to study. This summer, she was finally ready to start afresh – only to find the job market was dire.

So while applying for jobs, Xue joined the challenge to keep her monthly food budget under $70. Her husband, who works long hours, usually eats at his company cafeteria, meaning Xue most often cooks for herself.

She quit ordering deliveries and learned to cook, scouring the internet for the best deals on meat and vegetables.

“I feel I’m spending two-thirds less than when I had a job: Ordering delivery for two meals a day used to cost at least 60 yuan [$8], which now can last three to four days in my money-saving mode,” Xue said in an interview.

She expects her money-saving mode to last even when she finds another full-time job. “I will be more conscious of saving and try not to live from paycheck to paycheck again,” she said.

‘Cost-efficient’ rather than ‘stingy’

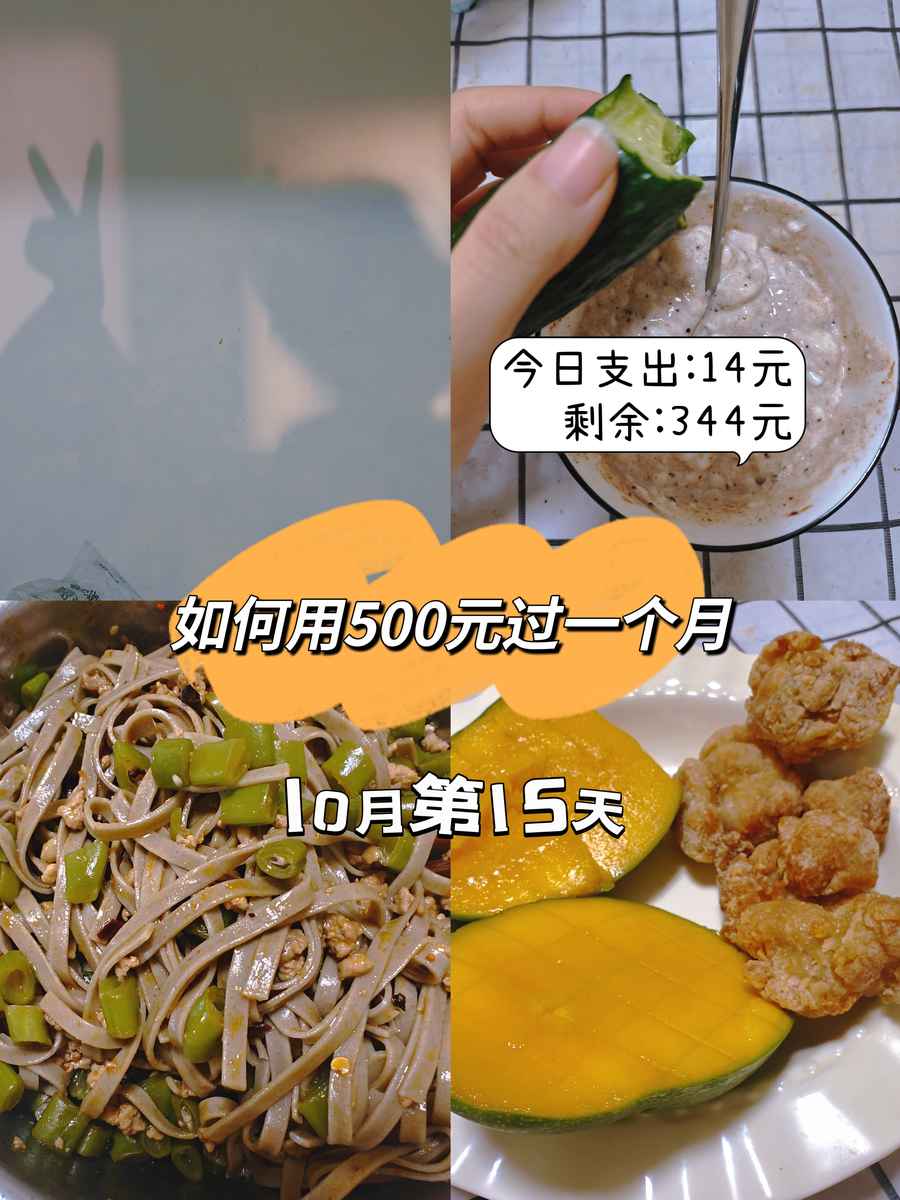

Zhao Yongfang posted the meals she ate on Oct. 15: noodles and green beans, mango and fried chicken, cereal and a cucumber.

Zhao Yongfang approached the spending challenge as a way to accelerate her efforts to return to her normal weight since giving birth three years ago.

So when the 32-year-old engineer, who usually lives in Xi’an, was posted to work in Beijing for a couple of months, she figured it was the perfect time for her to combine her diet and the spending challenge. After all, she was living in company housing and had almost no social life, and Zhao and her husband had already become more intentional about money since their son arrived.

“At first I thought it wouldn’t work: How could I possibly live with less than 20 yuan [a day] in a first-tier city?” Zhao said. But she soon realized it was feasible, especially when her boss picked up the tab for work meals.

When she needed to cook for herself, Zhao found cheap groceries from neighborhood markets, making tomato soup and fried rice, or a DIY hotpot, and often packing lunch. When she wanted a snack or dessert, she splurged on fried chicken or cake.

Unlike many Chinese who prefer hot dishes, Zhao doesn’t mind cold food. That made it easy to keep her dinners very simple: a bowl of cereal and milk, accompanied by a cucumber or a banana.

“I don’t see it as a challenge of being stingy: Experimenting with a tight budget made me rethink how I can make my lifestyle healthy and my diet cost-efficient,” she said.

Budgeting to save for a home

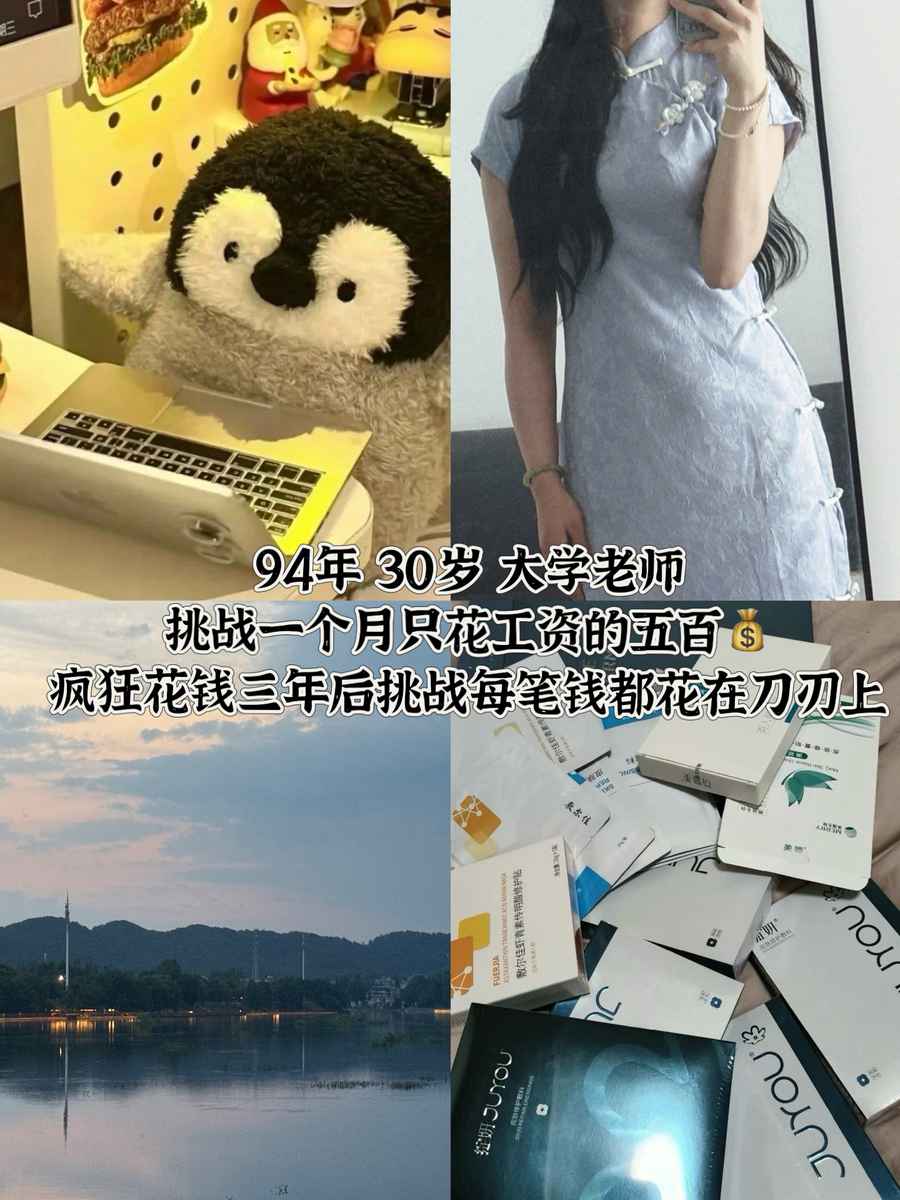

“After three years of crazy spending, it’s a challenge to spend every penny wisely,” Helena Liu wrote.

Turning 30 this year motivated Helena Liu to start saving for her own home, so she looked for ways to cut her costs.

A college lecturer in Henan province, Liu already lives rent-free in campus housing, but she was spending as much as $100 a month on food.

So she signed up for the challenge – and was hoping to bank the difference.

For breakfast, Liu has two boiled eggs and some soy milk. On weekdays, she usually gets the lunch set – one meat and two vegetable dishes – at her college cafeteria for options. For dinner, she gets a steamed bun and vegetables from street vendors. Total: $2.50 a day. When she wants to splash out, she buys a pack of chicken breasts for 70 cents from her neighborhood supermarket.

Doing the challenge has been “pain-free,” Liu said.

That’s partly because she grew up with little in a working-class family, although as she became an adult she developed a penchant for fast fashion and stuffed animals. “That was a fleeting spark of joy created by the consumerist society, never driven by my existential needs,” she said.

The spending challenge convinced Liu that she has enough self-discipline to shop less, save more and make longer-term plans. Even though that might now mean moving to a bigger city.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

South Korea Prosecutor Seeks Death Penalty for Ex-President Yoon over Martial Law (Update)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

-

Suzuki Overtakes Nissan as Japan’s Third‑Largest Automaker in 2025

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Alls from Record as Tech Shares Retreat; Topix Rises (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation