Unbalanced Information Diet: Protecting the Facts / Consumers Tricked Into Subscription Contracts Online;Dodgy Merchants Use Small Print, Confusing Language

A woman who cancelled a subscription that her father inadvertently agreed to online shows the shopping website saying, “They intentionally make the cancellation procedure difficult.”

The photo has been partially obscured.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

17:13 JST, April 24, 2024

This is the third installment in a series examining situations in which conventional laws and ethics can no longer be relied on in the digital world, and exploring possible solutions.

***

Shady operators are adept at using tricks called “dark patterns” to manipulate online consumers into making unintended purchases or ensnaring them in unwanted contracts.

In the summer of 2022, a 48-year-old part-time worker in Minami-Alps, Yamanashi Prefecture, was visiting her 80-year-old father nearby when he said, “I want to cancel the contract but I cannot get through on their phone line.” He was upset and irritated, holding his mobile phone in hand.

A few days earlier, he had made an online purchase of a beauty serum advertised as removing skin spots and priced at ¥1,980. He thought it was a one-time purchase. After the first purchase, however, he received an e-mail saying that he had signed a contract for a subscription to the product and that the price was nearly ¥6,000 for the second and subsequent purchases.

The daughter called the vendor’s number on her own smartphone to cancel the subscription on behalf of her father. However, all the calls went straight to voicemail. “The phone line is very busy,” they were told.

So, she switched to the Line app and sent the vendor a message saying that her father wanted to cancel the subscription. Following several exchanges of messages, two options appeared on the screen: One was “Will you really cancel it?” and the other was “Have you decided not to cancel it?”

She chose the first option without hesitation. However, it actually referred to the cancellation of the process to cancel the subscription. So she had to redo the process from the beginning.

The vendor was engaging in “obstruction,” or “making it hard to cancel a service,” which a paper from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development lists among several examples of dark patterns.

After that, messages trying to stop her from canceling the subscription appeared one after another, such as: “You will lose all the points after you cancel the subscription.”

This was “nagging,” another example of a dark pattern.

“I was so tired that I almost gave up halfway through,” she said.

After she canceled the subscription, she checked the shopping website and found wording suggesting a subscription purchase. However, the words were written in a much smaller font size than those of the initial price and other advertising phrases.

This fits yet another dark pattern listed by the OECD: “interface interference, e.g. visual prominence of options favourable to the business.”

“Elderly people tend to sign contracts without carefully reading the terms and conditions. This method is unfair and awful,” the Minami-Alps woman said.

The Yomiuri Shimbun asked the vendor for an interview, but they did not respond.

In 2022, consumer affairs centers across the country received a total of about 75,000 complaints and inquiries about “subscriptions” in mail order sales including online sales, increasing 47% from the previous year and reaching a record high number. People 65 and older made about 30% of all inquiries, and nearly 70% of those were about online subscriptions.

But it is not just the elderly who are at risk. Dark patterns could cause consumer trouble for anyone.

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Kesennuma, Miyagi Pref., Locals Raise Carp Streamers as Symbol of...

-

Iran Situation: Significance of Rule of Law Must Be Conveyed

-

Toyota Advancing Plant-Based Biofuel Development in Fukushima Tow...

-

Trump Says Iran Had a New Site for Developing Nuclear Weapons

-

2 People Reportedly Found on Mt. Fuji; Hiking Trail Currently Clo...

-

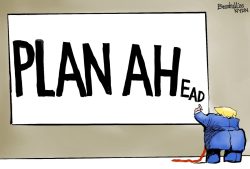

CARTOON OF THE DAY (March 10)

-

Rapeseed Flowers Reach Peak Viewing Period at Tokyo's Showa Kinen...

-

Memorial Service Marks 81st Anniversary of Tokyo Air Raid; Crown ...

Popular articles in the past week

-

Ibaraki Pref.'s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

-

Amid Strait of Hormuz Blockade, Shipping Companies Scramble to Ge...

-

Govt to Utilize ODA for Ensuring Economic Security; Securing Ener...

-

Japan Govt Survey Finds Just 10% of Workers Want Working Hours to...

-

Japan's 2nd Round of U.S. Investments May Be Worth Over $100 Bill...

-

Nippon Life Insurance's U.S. Arm Sues OpenAI Over Legal Assistanc...

-

Imperial Family Watches World Baseball Classic Game Against Austr...

-

Beckoning Cats Get Makeover to Fit Modern Lifestyles with Sleek D...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanes...

-

South Korea Tightens Rules on Foreigners Buying Homes in Seoul Me...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

-

Ibaraki Pref.’s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed