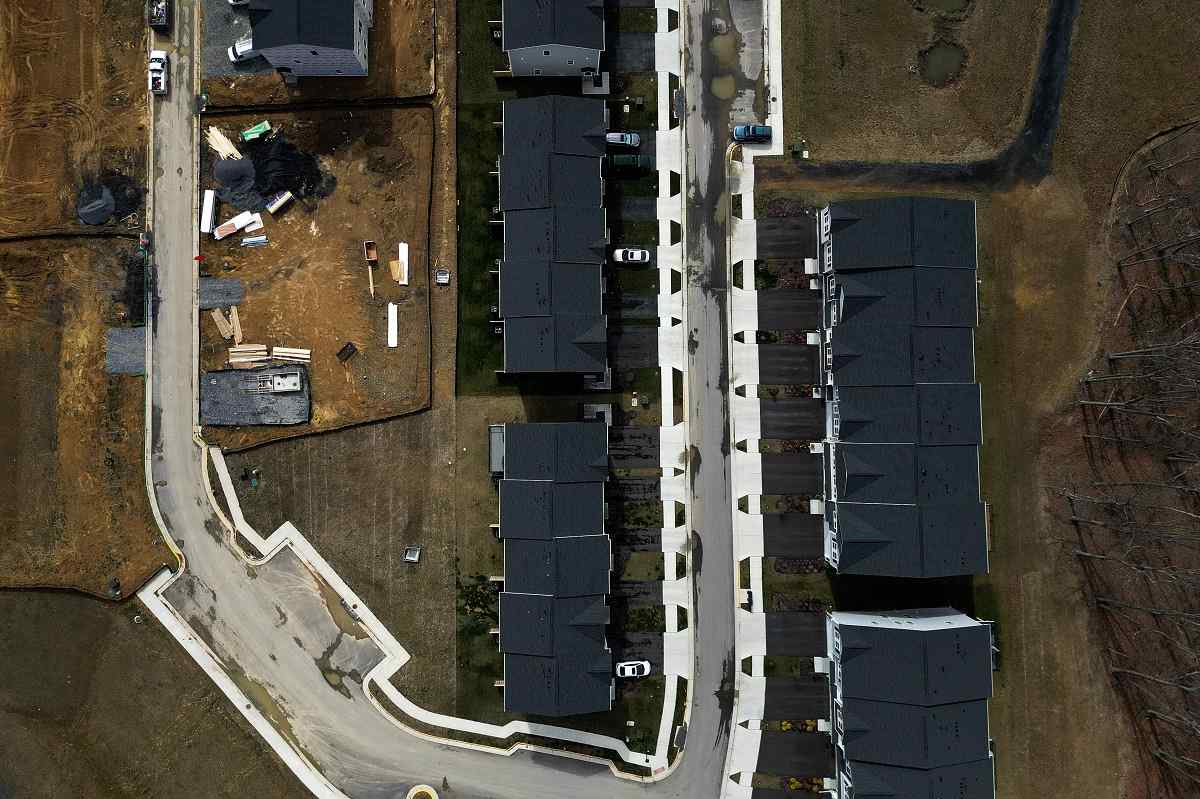

A townhome community in Frederick County, Va.

13:40 JST, March 11, 2024

The new American home is shrinking.

After years of prioritizing large homes, the nation’s biggest and most powerful home builders are finally building more smaller ones, driving a shift toward more affordable housing.

The boom in smaller construction has cut median new-home sizes by 4 percent in the past year, to 2,179 square feet, census data shows, the lowest reading since 2010. That’s helped bring down overall costs and contributed to a 6 percent dip in new-home prices in the same period.

Townhouses, in particular, are increasingly popular, accounting for 1 in 5 new homes under construction at the end of 2023, a record high, according to an analysis of census data by the National Association of Home Builders. To cut costs, companies are building smaller and taller, with fewer windows, cabinets and doors.

Altogether, this wave of new construction promises a crucial first step toward addressing a critical shortage of starter homes that has sidelined first-time home buyers and contributed to inflation.

“Even a slightly smaller home can be thousands of dollars cheaper – for both builders and buyers,” said Andy Winkler, director of housing and infrastructure at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington think tank. “This is a trend driven by just how unaffordable housing has become, with sky-high prices, rising interest rates and so few homes for sale.”

Nikki Cheshire kicked off her home search in Frederick County, Va., with a wish list: three bedrooms, an attached garage and a yard for her dog. But she quickly realized she’d have to think smaller.

The stand-alone houses she toured were well beyond her $450,000 budget. Cheshire looked for six weeks, was outbid twice and eventually landed a newly constructed townhouse for $408,000. It checks all the boxes, albeit at a smaller scale – the garage, for example, fits one car, not two. But more importantly, she said, it’s affordable.

“I looked at so many houses, but so many of them were too big and too expensive,” said Cheshire, 29, who works in corporate communications. “The one I got – yes, it’s smaller and doesn’t have everything – but it’s enough.”

Top: Townhouses in Frederick County.

Bottom: Nikki Cheshire pets her dog Bishop in the living room of her Frederick County townhouse.

This new trend is an about-face from early in the pandemic, when Americans sought out larger living spaces. Many moved into sprawling homes on the outskirts of town, sending luxury-home prices soaring. Extra pandemic savings, combined with rock-bottom interest rates, made it possible for many families to buy homes for the first time or upgrade to larger, more expensive properties.

As a result, median home prices have jumped a whopping 28 percent in the past four years, to nearly $418,000. At the same time, mortgage rates have more than doubled to almost 7 percent, down slightly from a 23-year high reached in November. Taken together, homes in the United States are less affordable than they’ve ever been, according to Goldman Sachs.

A shortage of homes, especially smaller, more affordable entry-level ones, has added to the problem. Builders for years have focused on more profitable properties, with construction concentrated in two extremes: houses on large suburban lots, or steel-and-concrete apartment buildings in urban areas, according to Robert Dietz, chief economist for the National Association of Home Builders.

That has slowly begun to change, as home builders face higher borrowing costs and growing demand for more affordable options. In earnings calls, some of the country’s largest publicly traded home builders have said they are rethinking their plans so they can prioritize smaller, more affordable housing. D.R. Horton, the country’s largest home builder, sold more than 82,000 homes last year, most of them under $400,000 and to first-time buyers. Its lineup now starts at about 900 square feet.

“We are continuing to shift … to more and more of our smaller floor plans to address affordability issues in the market,” Jessica Hansen, senior vice president of communications, said in a November earnings call.

Even Toll Brothers, known for its high-end properties with an average sales price of $1 million, is downsizing to lower-priced options, which are also faster to build. Sales of “affordable luxury” homes – starting at about $400,000 – more than doubled in the past year, outperforming more expensive properties.

“With 75 million millennials out there, we were not going to wait for them to hit their 40s and buy their move-up home,” chief executive Douglas Yearley said in a December earnings call, adding that he expects entry-level homes will eventually make up 45 percent of homes sold by the company. “I’m really proud of how … we went after the more affluent first-time buyer.”

The housing crisis has been an ongoing challenge for the Biden administration. In his State of the Union address, the president proposed sweeping measures to encourage more entry-level homeownership, including building and renovating 2 million affordable homes and offering $9,600 in tax credits that Americans could put toward a mortgage.

“I know the cost of housing is so important to you,” President Biden said. “Inflation keeps coming down, and mortgage rates will come down as well. But I’m not waiting.”

Prices for entry-level homes – which hit a record $243,000 last year, according to Redfin – have risen rapidly since the Great Recession, when home-building activity slowed to a halt.

The country added fewer single-family homes in the 2010s than in any decade since the 1960s, according to Daryl Fairweather, Redfin’s chief economist, resulting in a shortage of millions of homes.

“It is clear that there simply aren’t enough homes to accommodate everyone,” said Orphe Divounguy, senior economist at Zillow, which estimates a national shortage of at least 4.3 million homes. “The decline in affordability meant buyers have pivoted to lower-priced homes, which includes what we could consider starter homes.”

Although price increases for luxury homes have moderated in recent months, entry-level homes have continued to get pricier, in part because of growing demand. Overall, starter home prices are up 2 percent from a year ago and more than 45 percent from 2019, Redfin data shows.

At the same time, borrowing costs have risen sharply since the Federal Reserve began hiking interest rates in early 2022 to bring down inflation.

The housing market has slowed precipitously in response, though the results have been uneven. The wealthiest buyers, who have enough cash to avoid borrowing altogether, have been undeterred by rising borrowing costs. But those on the lower end are having to cut their budgets and downsize their plans.

In Anaheim, Calif., first-time home buyers Anna Kolev and her fiancé began their home search in September and had to rethink their plans every week or two, as mortgage rates fluctuated, with a goal of monthly payments below 25 percent of their salaries.

“We’d have to reevaluate every time interest rates changed or prices started creeping up. It was like, ‘Are we still in the game? Can we still afford this?,’” the 29-year-old software engineer said. “We definitely had to temper our expectations of what kind of house we could afford.”

Earlier this year, they bought a three-bedroom house for $910,000. At 1,550 square feet, it’s about 200 square feet smaller than Kolev would’ve liked, but anything larger was prohibitively expensive, she said.

“We compromised on so many things: location, square footage, kitchen,” she said. “But we’re very lucky that we were able to buy at all.”

The acute need for more housing is forcing local governments to rethink zoning laws, lot size requirements and other land-use policies often geared toward keeping smaller homes out of wealthier neighborhoods. Portland, Ore.; Austin; Charlotte; and St. Paul, Minn., have all recently made changes that allow building as many as four homes on a single lot.

Some communities are going even further. Sheboygan County, Wis., is partnering with local employers such as Johnsonville, Kohler and Sargento Foods to build 600 entry-level homes as part of its effort to draw more front-line manufacturing workers to the area. The county will also offer down payment help for the new homes, priced at about $230,000 to $250,000.

Still, housing economists caution this spurt of smaller new homes makes up a sliver of the overall housing market. New construction also tends to be pricier than existing homes, putting it out of reach for many first-time home buyers.

“It’s going to be hard to fix this problem without more existing homes on the market, and clearly that’s a tough thing to solve for,” said Winkler of the Bipartisan Policy Center. “I’m generally skeptical we’re building enough true starter homes to put a dent in the housing shortage.”

Even if the shift holds, it would take years of sustained growth to build enough homes to satisfy demand, he said. Plus, there’s another wrinkle: Americans have long been conditioned to think bigger is better when it comes to housing.

“Smaller homes are cheaper at the moment, for both builders and buyers, but it’s hard for me to fathom this becoming a long-term trend,” he said. “Americans haven’t become suddenly enamored with small houses. They just can’t afford anything else.”

Three years ago, Gary and Christen Powers found the perfect first home for their family: a sprawling, 2,200-square-foot new build in Texas City, Texas, with two primary suites, including one for Christen’s aging mother. Then, before they could lock it in, wood prices soared, sending the home’s price tag from $287,000 to $340,000, well out of their budget.

They began looking again – on a smaller scale. Last month, they closed on a home that’s about 25 percent smaller, with three bedrooms instead of four. And, at $273,000, it was under budget.

“It’s on the small side,” said Gary Powers, 56, finance director for an LGBTQ mental health facility. “The bigger thing was finding something we could afford.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan