Tendo Shogi Pieces Garner Attention for High-Quality Production Techniques; Craftspeople Hope to Pass on Skills to Next Generation

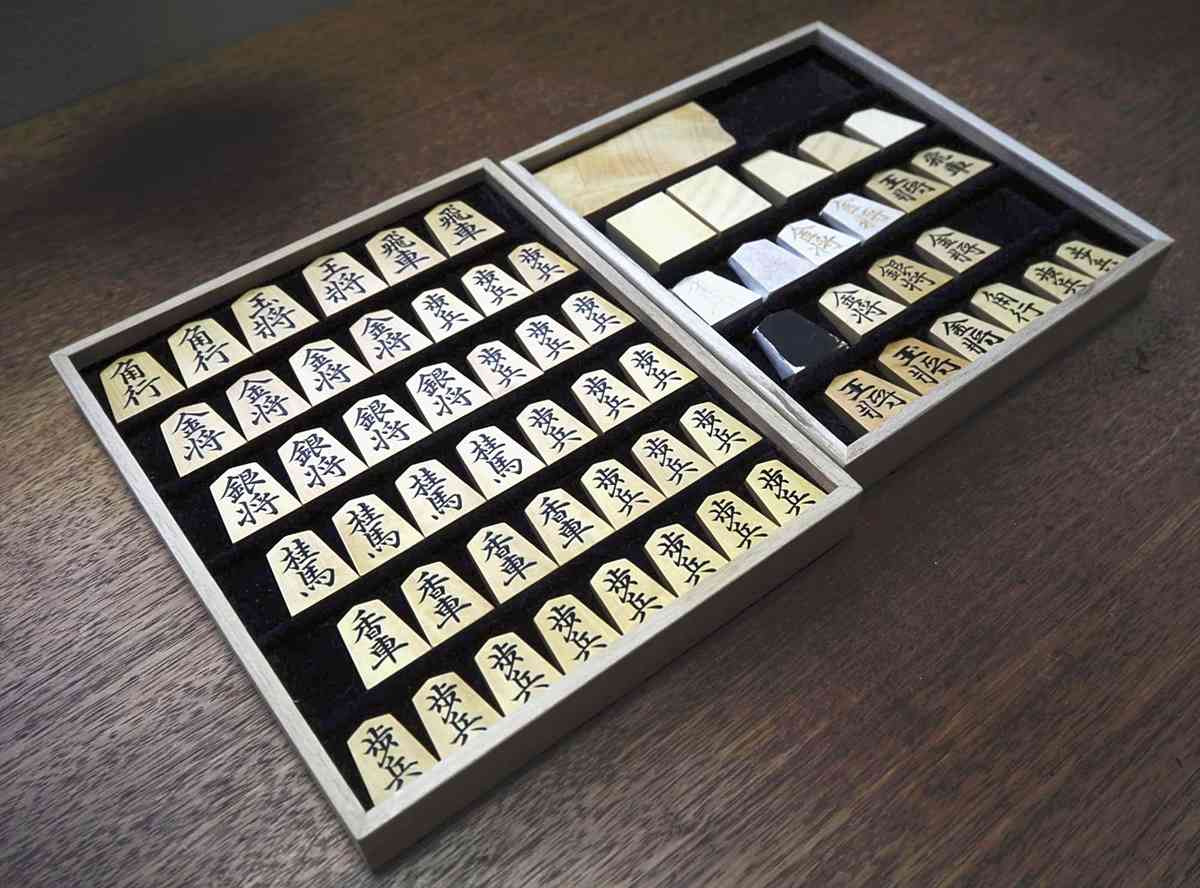

Shogi pieces Sakurai produced. The highest quality “moriage goma” pieces are seen.

13:00 JST, December 22, 2024

TENDO, Yamagata — A huge monument of a shogi piece in front of JR Tendo Station greets people getting off the train in Tendo, Yamagata Prefecture, a shogi piece production center famous for its high-quality techniques.

In recent years, the number of shogi fans who enjoy watching the game has increased, and it has become a popular topic of conversation.

The traditional event Ningen Shogi, or human shogi, is held in Tendo, Yamagarta Prefecture, on April 13.

The top-producing area in Japan supports those who enjoy playing the traditional game with the pieces made here. The history of Tendo’s shogi pieces dates back to a time when feudal retainers of the Tendo clan began making the pieces as a side job in the late Edo period (1603-1867).

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), when the industry was established in this area, the main products were pieces with characters written directly on the wood using lacquer.

During the Showa era (1926-89), the production of shogi pieces with stamped and engraved letters increased as the mechanization of production progressed in earnest. As a result, Tendo became known as a producer of shogi pieces throughout the country.

Over time, however, people came to have an image of pieces made in Tokyo as being more “high-class,” while Tendo’s were seen as “mass-produced.”

From the mid-1970s on, the demand for Tendo-produced pieces, which had been popular with the general public, began to decline due to the diversification of hobbies and the increase in demand for high-quality pieces. Kazuo Sakurai, 76, who had just begun his career as a craftsman at that time, was encouraged by an older apprentice to make high-end pieces amid a decline in traditional craftsmanship.

“We wanted the pieces from Tendo to be used in the shogi title matches,” he said.

Sakurai and his colleagues set out to create a “moriage goma,” the highest quality shogi pieces, which are made three-dimensionally by filling the carved characters with natural lacquer. Several layers of such lacquer are applied to create a raised effect.

Sakurai studied lacquer mixing and other techniques on his own. In 1980, the pieces made by another senior craftsman were used in a shogi title match. After that, the pieces made by Sakurai and his colleagues have become used one after another.

Ryo Sakurai carves characters into a piece of wood while smoothly moving a carving stand and a knife.

In 1996, Tendo shogi pieces were designated as a traditional handicraft by the government.

“The way people think [about Tendo shogi pieces] has significantly changed thanks to the high evaluation by people,” said Sakurai’s eldest son Ryo, 48, who also is a traditional craftsman like his father.

After nearly 30 years of training under his father, he makes the pieces used in title matches.

“As well as being beautiful, the pieces must be durable enough to allow the players to concentrate on their games,” he said.

While continuing to focus on machine-made carved pieces, the Shogi Pieces Makers Cooperative Society of Yamagata, which has 27 members, has tried to pass on and promote the shogi piece industry. It has aimed to do this by establishing a successor training course and a production demonstration facility run by graduates, and using shogi pieces as gifts in the furusato nozei hometown tax donation system.

Thanks to the success of shogi genius Sota Fujii, who holds seven out of eight major titles, and other players, the shogi world is experiencing a boom.

“I’m thankful that there is also a lot of attention being paid to shogi tools,” Sakurai said. “It’s not easy to make a living just making shogi pieces, but I want to play a role in passing on the local industry to the next generation.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan