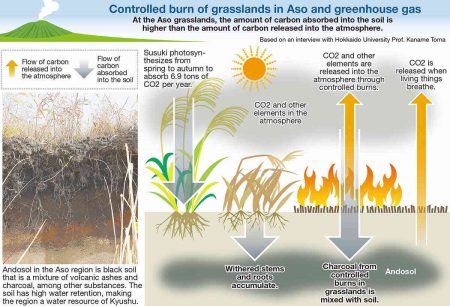

Controlled Burns at Aso Field Play Role in Combating Global Warming, Absorbing more CO2 than Emitted

Orange flames burn dead susuki silver grass, which has grown as tall as an adult human, in Aso, Kumamoto Prefecture, in April.

16:41 JST, December 2, 2025

Controlled burns are a springtime tradition in grasslands in the Aso region of Kumamoto Prefecture in Kyushu.

The aim of the annual event, in which dry grass is set on fire, is to encourage new plants and flowers to sprout.

Since ancient times, the practice has supported the region’s livestock farming and agriculture.

Recently, research has revealed that the burns help store carbon underground, contributing to the fight against global warming.

Grasslands since ancient times

Cattle eat fresh grass that sprouted on a slope after a controlled burn in Aso, Kumamoto Prefecture, in April.

Aso is home to Japan’s largest grasslands, which span about 22,000 hectares of the famous caldera terrain. Roughly the size of Saitama City, the grasslands are used to raise beef cattle, like “akaushi” Japanese brown cattle, and to produce compost. The vast amount of water in the soil flows into rivers like the Chikugo River and to prefectures throughout Kyushu, earning the grasslands the nickname “Kyushu’s water tank.”

The grasslands are maintained by residents and volunteers, who come from inside and outside the prefecture. Every spring, they conduct controlled burns over about 70%, or 15,000 hectares, of the area.

Research on plant-derived fossils preserved in the soil suggests that the grasslands stretched across Aso even during the Jomon period (ca 10,000 B.C.-ca 300 B.C.).

The ancient “Nihon Shoki” (eighth-century official chronicles of Japan) tells of a visit Emperor Keiko made to the area during a trip to Kyushu. Upon seeing the fields, which were so vast that there were no houses in sight, he asked, “Are there any people in this land?”

Records also show that the Aso region provided troops and horses to the Dazaifu regional government during the Heian period (794-late 12th century).

“Aso gets a lot of rain, so if left untended, the grass and trees grow thick quickly,” said Yuji Ueno of Aso Green Stock, a public interest foundation located in Aso that supports the controlled burns there. “The vastness of the grasslands is proof that controlled burns have continued for a long time.”

However, after World War II, chemical fertilizers became more widespread, and the livestock industry declined, leading to a shortage of people to carry out the controlled burns. As a result, some of the grasslands became overgrown, while one part became forest. Fearing the loss of the grasslands and the associated traditions, volunteers began working to preserve the area.

Different from wildfires

One day in April, about 40 people gathered to burn a hill spanning about 6 hectares. The hill was covered in dead susuki silver grass that stood nearly as tall as an adult human.

A fire was lit, and orange flames covered the hill in an instant, sending up plumes of white smoke. The participants watched, holding fire-extinguishing poles that were about three meters in length. Dead pampas grass crackled and popped as the flames spread in a band up to 10 meters high. In less than an hour, the entire hill had turned pitch black, and the fire died down.

“Controlled burns are completely different from wildfires,” Ueno emphasized.

Since only the year’s growth burns, the fire spreads and burns out quickly. Unlike wildfires, the heat does not penetrate deep into the soil, leaving seeds and buds intact for rapid growth in spring and summer.

“When the dead grass is gone, sunlight and rainwater can reach the ground efficiently,” Ueno said. “Controlled burns are essential for maintaining the grasslands.”

Secret in black soil

When grass and trees are burned, they emit greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane.

Prof. Kaname Toma, a specialist in soil science from Hokkaido University, has been studying the effects of controlled burns on global warming, the atmosphere and soil since 2009.

From spring to autumn, susuki grass absorbs a large amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Based on estimates on the amount of carbon in the soil, 6.9 tons of carbon is absorbed annually per hectare. For the entire grasslands, this equates to 70% more carbon absorption than the annual emissions of all households in the Aso region.

After the burn, the soil becomes andosol — a charcoal mixture of susuki, organic matter including dead roots and stems, and accumulated volcanic ash. The carbon content of Aso’s soil is among the world’s highest, with the amount of carbon stored in the soil from the atmosphere in one year believed to exceed the emissions from of the burn.

“Susuki grasslands are more effective at storing carbon in the soil than coppices or planted forests,” Toma explained. “Even when calculating greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere [from controlled burns], the practice contributes to mitigating global warming.”

Treasure trove of life

Higotai

The Aso grasslands are a treasure trove of life.

According to Yoshitaka Takahashi, chairman of the Aso Grassland Regeneration Council and someone who studies grassland ecosystems, some 600 plant species are found in the grasslands, including endangered species like the higotai echinops setifer, which blooms distinctively round lapis-blue flowers, and okinagusa narrow-leaved pasqueflowers. Rare birds and insects, such as orurishijimi blue butterflies and daikoku-kogane horned dug beetles, also inhabit the area.

“Residents have benefited greatly from the grasslands, using them to raise livestock, make fertilizer, gather roofing materials and more,” Takahashi said. “They also use the flowers and roots for medicine, sing about the nature there and use it to nurture their emotions.”

The grasslands have decreased to less than half their size over the past 100 years. The Environment Ministry is carrying out projects to research the Aso region’s nature and the history of the management there. It is also developing access roads that double as “firebreaks” to reduce the burden of preparing for controlled burns. This fiscal year, about ¥120 million is being invested in the projects.

“If we can conserve and regenerate the grasslands, we can put the nearly lost ecosystem back on the path to recovery,” said the director of the ministry’s Aso-Kuju National Park management office. “We want to focus our efforts on developing regional revitalization strategies centered on the grasslands.”

Related Tags

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

‘World’s Oldest Bio-Business’ Is Japan’s Seed Koji Retailing, Mold Used to Make Fermented Products like Sake, Miso, Soy Sauce

-

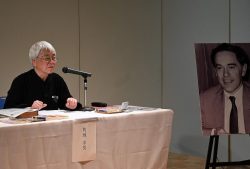

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts