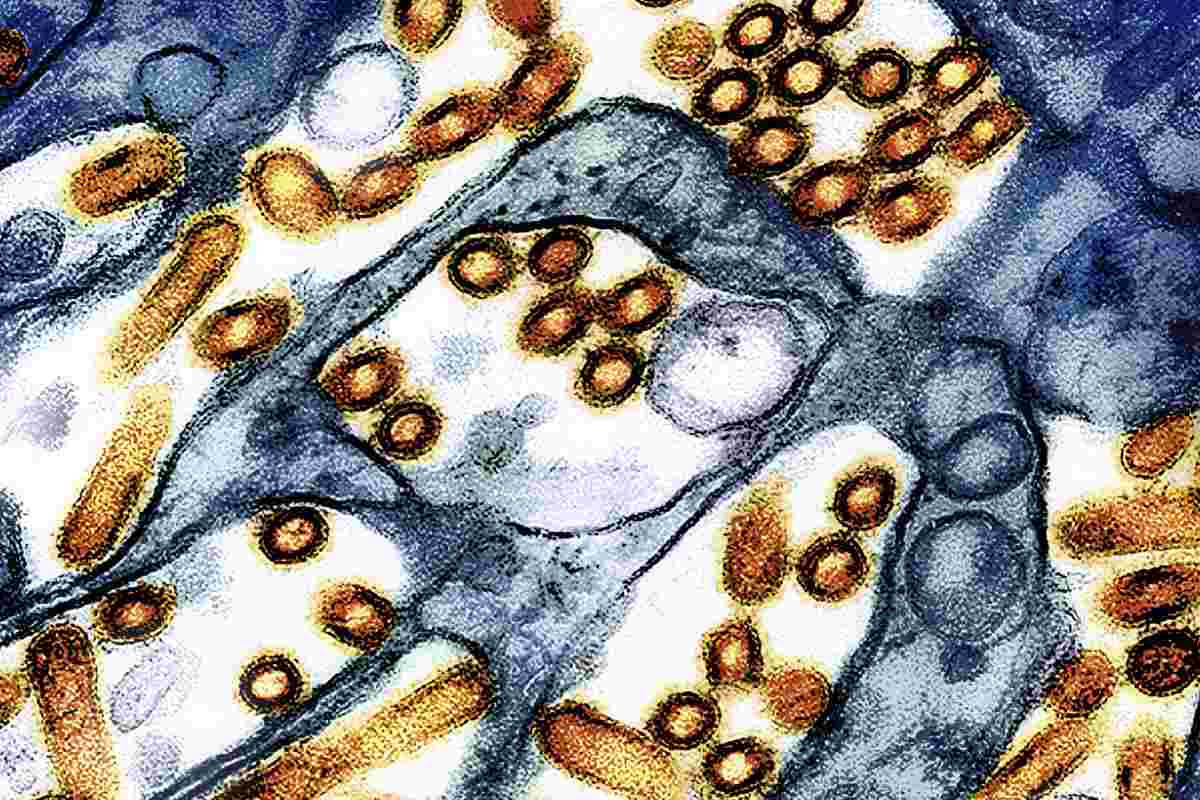

A strain of the bird flu virus seen under a microscope.

12:06 JST, November 15, 2025

Health officials in Washington state said Friday they have confirmed the first U.S. human case of bird flu since February, with a strain that has previously been reported in animals but never before in humans.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health officials said they consider the risk to the public to be low.

An older adult with underlying conditions preliminarily tested positive for the infection and has been hospitalized since early November, state health officials said Friday. The person developed a high fever, confusion and respiratory distress. “This is a severely ill patient,” state epidemiologist Scott Lindquist said during a briefing.

The person has a mixed backyard flock of domestic poultry at home that had exposure to wild birds, the state health department said in a statement. The domestic poultry or wild birds are the most likely source of exposure, but state and local health and agricultural officials are continuing to investigate how the person became infected.

State health officials said Friday that the person was infected with H5N5, an avian influenza virus that has previously been reported in animals but not in humans. It is part of the family of avian influenza viruses, and has been seen in wild birds in other U.S. states and Canada, state officials and experts said.

But it’s different from the H5N1 strain, which is by far the most common in animals and humans, and has been spreading widely among wild birds, poultry and other animals around the world for several years. Starting early last year, H5N1 infections began showing up in people and dairy herds in the United States. A Louisiana man with backyard poultry died in January, but most of the infected people have had mild illnesses.

The Washington patient’s H5N5 infection is an important scientific and epidemiological development, but “the new information does not change the investigation, the public health response or guidance to the public,” said Washington state health officer Tao Kwan-Gett.

The public health agencies and hospitals have followed everyone who has had contact with the patient – including more than 100 health care workers – monitoring them for influenza-related symptoms and testing those with symptoms, officials said.

“We have identified no additional individuals other than the patient who is infected with H5N5,” Kwan-Gett said.

Infections from an H5N5 virus as opposed to an H5N1 virus isn’t reason for specific concern, said Richard Webby, a virologist and influenza expert at St. Jude’s Children Research Hospital. “The H5N5 viruses we have looked at behave similarly to H5N1 viruses in our models to assess human risk.”

The Washington patient cared for a backyard flock, and two birds died of illness a few weeks ago, but the rest of the flock remains healthy, according to state veterinarian Beth Lipton. Testing of the birds is ongoing, she said. Wild birds also had access to the person’s property, she said.

The CDC is coordinating with Washington state and monitoring the situation closely, said Andrew Nixon, a spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services. Lindquist said CDC experts have been in direct contact with clinicians to give “state of the art recommendations about patient management for this patient.”

No person-to-person spread has been identified in the United States with bird flu at this time, officials said. But people with job-related or recreational exposures to infected birds or other animals are at greater risk of infection.

There have been no reported human infections in the United States since February, but poultry flocks infected with H5N1 began increasing in September. (November so far has had 25 flocks infected in the first two weeks of the month, already more than the total for September.)

Federal and state health departments conduct influenza monitoring year-round, but the risk of avian influenza increases in the fall and winter because migratory birds can carry the virus and spread it to domestic animals, including commercial poultry farms and backyard flocks, increasing the potential for spillover to humans, said Seema Lakdawala, a virologist at Emory University who studies the transmission of the influenza virus and is co-director of Emory’s Center for Transmission of Airborne Pathogens.

Health officials are also on alert in the coming weeks for an increase in seasonal influenza because some countries in the Northern Hemisphere, including the United Kingdom, Japan and Canada, are starting to see an unusually early start to the season, with some severe cases reported because of a mutation in one of the dominant flu strains circulating globally. Seasonal influenza remains low across the United States but is increasing, according to the CDC, which updated its flu surveillance Friday for the first time since the shutdown.

Of the 70 infections reported in people in the United States from 2024-2025, most were in workers exposed to infected dairy cattle and infected poultry. There were two cases with backyard poultry exposure and three cases with unknown exposure.

People with mild illness may be less likely to seek medical treatment, and immigrant farm workers may be reluctant to seek medical care because of their legal status amid the Trump administration’s deportation push, public health experts have said. The most recent infections confirmed by the CDC were in early February in Nevada, Ohio and Wyoming, from exposures to infected dairy cattle or poultry.

Bird flu isn’t the only disease linked to animals raising concerns in the United States. New World screwworm, a flesh-eating parasite causing an outbreak in Central America, has raised concerns that it could spread to the United States and devastate cattle and livestock. Animal health experts are also monitoring African swine fever, a deadly virus infecting pigs in many countries. It’s harmless to humans, but people can spread the disease by bringing pork or pork products with them when they travel from a country where the virus exists.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Arctic Sees Unprecedented Heat as Climate Impacts Cascade

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

South Korea Prosecutor Seeks Death Penalty for Ex-President Yoon over Martial Law (Update)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

-

Japan’s Nagasaki, Okinawa Make N.Y. Times’ 52 Places to Go in 2026

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time