Kevin Ramundo of Citizens for Fauquier County and Cindy Burbank of Protect Fauquier in Warrenton, Va., on Feb. 10, 2023.

12:36 JST, February 14, 2023

WARRENTON, Va. – For some residents, this small town in the Virginia Piedmont seems like the last logical place to put a warehouse full of computer servers.

Surrounded by horse farms, vineyards and million-dollar estates, it functions as the historic downtown for a community that is fiercely protective of its rural character. Boldface names ranging from actor Robert Duvall to candy heiress Jacqueline Mars have flocked to the hills just a few miles north – and helped bankroll efforts to keep their bucolic region just as it is.

But now, Amazon wants to build a data center here.

On an empty, 42-acre lot near the entrance to town, the tech giant has been waging an increasingly tense campaign to construct another facility for its cloud-computing business, a growing presence in the D.C. suburbs that has also faced increasing pushback. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

Many local officials in Northern Virginia have sought to attract this lucrative industry for the tax revenue it can generate without requiring much in terms of government services – at times, prompting protests or grumbles from neighbors.

Yet Amazon’s push into Fauquier County has helped animate an opponent that is locally influential enough to go toe-to-toe with the multibillion-dollar company: the area’s well-connected landowners and the conservation groups they fund.

In glossy publications, packed town halls and on yard signs across town, these critics have warned one data center could lead to many others, bringing constant noise and 120-foot-tall power lines to this rural area. Some have pointed out that the company hired Warrenton’s former town manager just weeks after she resigned – a move, they say, raises “serious questions” about whether something is being hidden, they say.

“Any reasonable human being would be wondering about the whole process and whether the town council is making decisions in the best interests of the people who elected them,” said Kevin Ramundo, president of the nonprofit Citizens for Fauquier County. “It’s the wrong use for this location, it’s the wrong location for a data center, and the way it’s all come about has been wrong, too.”

Questions from groups like Ramundo’s have at times turned into gripes about standard economic development practices, but the company has stayed almost entirely silent on the matter in public.

Amazon Web Services spokesman Duncan Neasham said in a statement that the company maintains a “robust code of business conduct and ethics” and “well-established business practices” that AWS employees are required to follow. He did not say why the company was looking to build a data center on this particular site in Warrenton.

“With the Town of Warrenton, we openly engaged the community through meetings, public filings, and hearings in our aim to build a data center that will bring significant investment, highly-skilled jobs, and a boost to the local economy,” Neasham said in the statement.

Ahead of a vote expected Tuesday on Amazon’s plan, the feeling in this historic, quaint community – known for the shops and brick sidewalks on its centuries-old Main Street – has turned tense.

As Amazon looks to build more data centers across the commonwealth, the recent tensions are a case study of what can happen when Big Tech comes to a small town: a bitterly contested election, resignations, a lawsuit and packed meetings.

***

Citizens for Fauquier County, the group now led by Ramundo, was founded in 1968 to fight off a “planned cluster development” that would have added thousands of homes to a farm property near Warrenton, the county seat and economic center of Fauquier.

As sprawl reached across Northern Virginia, the group and its affiliates pushed to preserve historic sites and stop projects such as a dam, a shopping center and a 42-bed hotel to keep development from overtaking this rural county. In 1995, some of its current members successfully pushed to prevent Walmart from building a superstore on the edge of town.

The Piedmont Environmental Council, which formed only a few years later, took on a similar mission at a regional level: Working across nine counties, it looked to conserve natural resources and plan development where it makes the most sense. Among other efforts, it blocked transmission lines across the region, helped protect hundreds of thousands of acres under conservation easements, and sparred with the co-founder of BET as she tried to open a high-end resort.

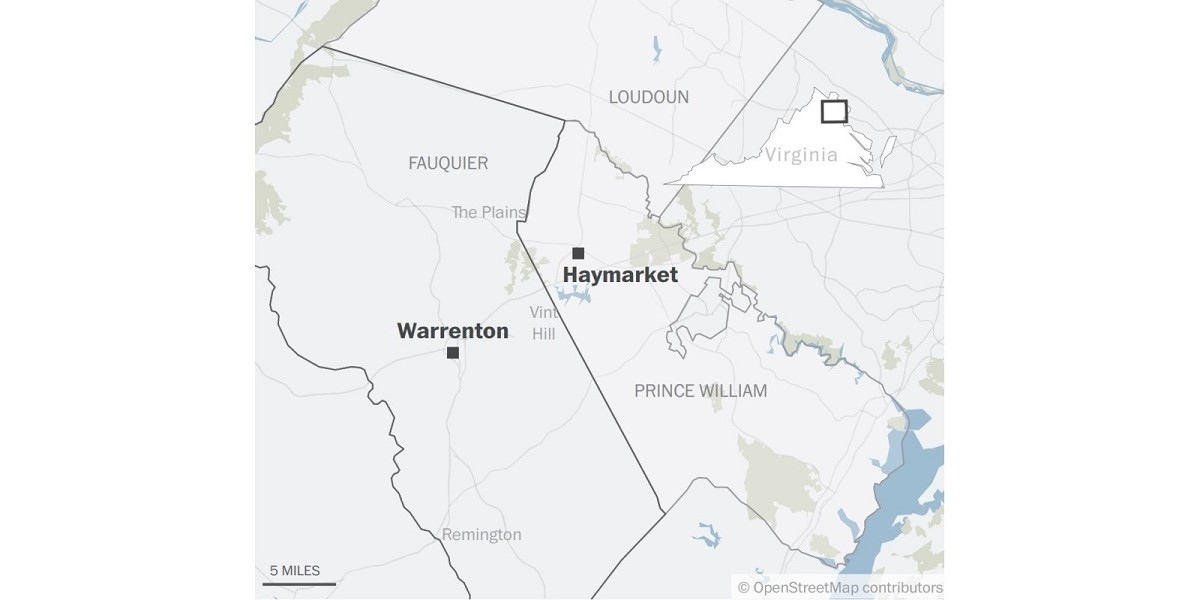

But both groups won what is perhaps their biggest victory against Disney, which made headlines in the early 1990s with a plan to construct a massive U.S. history-themed amusement park about 12 miles west in Haymarket.

That proposal quickly revealed a sharp regional divide. While “Disney’s America” was welcomed by many blue-collar Prince William residents with hopes for economic prosperity, their neighbors in northern Fauquier saw disaster.

The PEC co-chair warned the Disney project would waste taxpayer money on highway improvements and prompt a surge of “cheap motels and cheap stores.” Academics at the national level worried it would ruin nearby battlefields and present a Disneyfied version of history, and others spoke out against economic incentives offered by Virginia. To pressure the company to set up elsewhere, the PEC launched a splashy campaign that urged, “Disney – Take a Second Look.”

The critics won, and their victory cemented the notion among some that Fauquier conservationists were opposed to most development. If God wanted to move heaven to Haymarket, according to a joke at the time, the PEC would say, “God – take a second look.”

Mary Ann Ghadban, who owns property in northern Fauquier and has clashed with the group over data centers near her Prince William farm, suggested that the PEC has carried on that philosophy in western Prince William County.

“Unfortunately, they write their own facts in order to obtain their objective, which is to stop any opportunity in bordering [counties],” she said. “The PEC has never met a cause that wasn’t a great fundraiser and an opportunity to flex their political muscle.”

Among the group’s recent board members and top donors are Jean Perin, a close friend of Jacqueline Kennedy who once redesigned the White House Rose Garden; George L. Ohrstrom II, the scion of a fox-hunting private equity dynasty; and Mars, a billionaire equestrian and heiress to the M&M candy empire. Duvall, the Academy Award-winning actor who owns a 360-acre farm in northern Fauquier County, even filmed a video to raise money for the group.

Chris Miller, the PEC’s president, acknowledged the organization has wealthy donors and board members who contribute to its $6 million budget. But he said the nonprofit advocates on behalf of people of all socioeconomic backgrounds to protect the environment across the Virginia Piedmont.

“We’re lucky to have people who have resources, thank God,” he said during an interview at the group’s headquarters, a converted 1780s farmhouse off Warrenton’s Main Street. “We’ve also done an amazing amount of public benefit work using those resources.”

(Ramundo, CFFC’s president, noted that his organization – which is more confrontational and grass roots, with $65,000 in donations last year and no full-time staff – draws many of its board members from Warrenton proper. More than three-quarters of its contributions are $100 or less.)

The PEC expressed its support for data centers as these facilities sprang up in the suburbs of eastern Loudoun County. But as those facilities started exploding across the region, including in environmentally protected areas, that began to change.

Amazon data centers near houses at the edge of the Loudoun Meadows neighborhood on Jan. 20, 2023, in Aldie, Va.

***

Data centers had long been talked about as a possible addition to Warrenton. As early as 2011, town officials had discussed rolling back zoning rules that made these facilities illegal – and voted in 2017 to explore how to do so. But the effort to bring such a facility to Warrenton didn’t take off until Amazon came knocking two years ago.

There were easier options elsewhere in Fauquier County. Amazon had received approval in 2015 to build one facility at a classified federal complex right outside town. Some unincorporated parts of the county, including sites near Remington and Vint Hill, contained dozens of acres that had been rezoned to allow data centers – and at least one actual facility – without any special permission from local lawmakers.

But Warrenton may be eager for the data center and the lure of tax dollars.

Many of the wealthiest Fauquier landowners live outside the town limits, so Warrenton does not collect taxes from their properties. In this middle-class town of about 10,000 people, where the aging population seems averse to tax increases, a data center would be a fast injection of cash for town services.

Nearly two years ago, John Foote and Jessica Pfeiffer, two land-use attorneys at a well-known Northern Virginia firm, contacted Town Manager Brandie Schaeffer with a request to connect about a potential data center.

At this point, zoning rules made it illegal to build data centers anywhere in town, even in a few areas set aside for industrial uses. In a comprehensive plan mapping out future development for Warrenton, lawmakers continued to exclude data centers.

Still, Schaeffer and the council moved to explore changing that in April 2021. Foote offered in subsequent weeks to send Schaeffer drafts of what a change to zoning code might look like, according to emails obtained by CFFC and then independently by The Washington Post through separate public-records requests. And notes from a private May 2021 meeting indicated that Warrenton town staff agreed to provide a draft of the proposed zoning change to Foote.

But when town staffers were asked at a public meeting which data center companies were interested in Warrenton, they initially declined to say, according to video of that meeting.

Miller, the PEC president, said the lack of transparency around these exchanges had made the process look especially secretive. “You’re not playing fair. You’re trying to do things in secret, just trying to cut deals behind closed doors,” he said. “The public concern starts to go way up because it’s not a collective decision. It’s the decision of a few people operating in secret.”

Amazon initially declined to allow Schaeffer to comment on the record, and Foote and Pfeiffer did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Other public records obtained by CFFC turned up nondisclosure agreements between Amazon and two people on Schaeffer’s staff. And they also showed that the company’s representatives had been meeting in small groups or one-on-one with town council members.

Neasham, the Amazon spokesman, said: “Regarding the use of confidentiality agreements to safeguard trade secrets and intellectual property, Warrenton officials have noted themselves that this is common practice for companies seeking to do business in their community.”

The town council voted in August to approve the zoning amendment, which would still require the body to approve a permit application for any data center. Amazon purchased a property on Blackwell Road just a few weeks later for $39.7 million, paying more than 11 times the lot’s assessed value.

In 2022, a few months after Amazon submitted its formal application, Schaeffer announced she would be stepping down from her job as town manager. “After several years, it was time for my career to transition so I could balance the needs of my family,” she said in a statement to The Post, “after serving the town with the level of intense dedication and work its citizens deserve.”

Her announcement in June was followed by additional career news: She soon would start a job in economic development at Amazon Web Services, working to help build data centers across Northern Virginia.

***

The original vote by town lawmakers to allow data centers appeared to draw little attention from residents in Warrenton or elsewhere in Fauquier. Just three people testified in person at public meetings or submitted written comments – two of them in favor of the change.

Ramundo, of CFFC, said the group did not chime in, adding that it is not categorically opposed to data centers and had “no reason to believe” the Blackwell Road site could be used for such a facility. And Julie Bolthouse, PEC land-use director, said her organization did not see that it could bring about more power lines and more data centers.

‘We were still in the learning stages and we didn’t have the benefit of information that the [town] staff had,” Bolthouse said. “My calculations in my head were that there are some data centers that would be good revenue generators that might actually fit in the town.”

It wasn’t until spring 2022, when Amazon had submitted its permit application and Dominion Energy explained how it planned to power the facility, that conservation groups started a full-court press. One Dominion proposal included a substation next to Amazon’s data center and new 120-foot-tall transmission lines stretched across parts of eastern Fauquier.

PEC, CFFC and a new volunteer group, Protect Fauquier, wrote missives to town leaders, distributed fliers at Warrenton’s “First Friday” festivals downtown, and spread white-and-red yard signs around the county that read, “Stop the Power Towers.”

“This isn’t just about one data center,” Ramundo told the audience at a packed community town hall in October, for which the groups had rented out the auditorium of a private school. “This is about all the data centers that we think are going to follow.”

Speakers at the event raised concerns about the proposed data center: They said it would go against the comprehensive plan. They said one data center could result in unsightly power lines and more facilities later on. They pointed to the NDAs, the one-on-one meetings and Schaeffer’s hiring. They noted that her husband, Chris Granger, had resigned from his post on the Fauquier County Board of Supervisors over the potential for perceived conflict of interest with Amazon.

Neasham said Amazon had followed its standard equal opportunity hiring practices with Schaeffer, “filling a publicly posted role with an applicant who was rigorously vetted like any other candidate.”

Still, outstanding questions for residents across Fauquier animated vigorous opposition into the fall: Ramundo’s group unsuccessfully sued Warrenton over some of those requests. Nearly 2,000 people signed Protect Fauquier’s petition to oppose both a data center and a substation at the Blackwell Road property, although less than one-third listed a home address with a Warrenton Zip code.

The controversy also seeped into local politics, animating many conservationists to oppose incumbent Mayor Carter Nevill and back town council member Renard Carlos instead.

A separate political action committee formed by several CFFC board members, which called itself the Warrenton Honest Government League, sent out mailers attacking Nevill. They added red scrawl to the message on one of his yard signs – “Working together. Finding solutions.” – that changed it into a very different message: “Working with Amazon. Finding solutions for data centers.”

The few letters sent to the town council by residents in support of the data center – such as one from Andy Budd, who owns the Chevrolet dealership next to the proposed data center site – slammed CFFC as “privileged few elitists” who obstructed any development on that industrial site. (The property was the same one where Walmart had been stopped decades earlier.)

***

Along Main Street in Old Town Warrenton, where shops show off quirky horse-shaped sculptures and assortments of yarn and Amish-made furniture, some windows are now dotted by a different sight: Valentine’s Day-themed signs that say, “Show up and speak out against the Amazon data center.”

Smoking a cigarette outside an Irish pub on the street’s brick sidewalk last week, hairdresser Adri Trejo, 25, said she didn’t understand what all the fuss was about.

“There’s nothing even there anyway,” she said of the Amazon lot, which sits behind a car dealership at the intersection of two major roads. “Cellphones, the internet, Zoom – we’re using data all the time, and it has to be stored somewhere.”

Down the street, though, Keith Peitler, 49, erupted into a knowing chuckle when a reporter asked for his thoughts on the facility.

“It seems like there’s been a lot of backroom dealing,” he said between sips of an after-work weissbier at a basement brewery. “The people who seem to benefit from this are few and far between. There doesn’t seem to be any real necessity for this.”

An IT manager who lives in Old Town Warrenton, Peitler said the town seemed to be fine in terms of revenue and argued there would be no sensible way to power the property if it comes to town. While Dominion has floated putting transmission lines underground as an alternative to new overhead lines, those cables would rip up the road on his quiet street, he said.

Of all sitting town council members, just three agreed to answer Post questions about the data center on the record: two who joined the body in January, and one, Bill Semple, who has been a longtime critic of Amazon’s proposal and whose wife was formerly on the CFFC board. All expressed deep skepticism about Amazon’s data center.

For 36-year-old Chris Murray, standing back outside the Irish pub, the division is simple: Some people are fervently against the data center, and most others don’t have much reason to care.

“There’s definitely a bunch of NIMBYism with the data center. But if someone told me we’d get $10 million, I’d be okay,” said Murray, a cybersecurity specialist who lives in Fauquier’s more agricultural southern end. “Amazon hasn’t shown up with a suitcase full of money to show the townspeople. I feel like if they did that, it would be different.”

Indeed, as dozens of people rallied by the conservationists crowded a town hall meeting last month, town council members decided to delay the final decision to Feb. 14. Amid the sea of red T-shirts that read “Stop the Power Towers,” just a few people spoke in favor of the project.

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

Japan’s Princess Kako Marks 31st Birthday, Contributed to Key Events This Year

-

Arctic Sees Unprecedented Heat as Climate Impacts Cascade

-

Brigitte Bardot, 1960s Sultry sex Symbol Turned Militant Animal Rights Activist Dies at 91

-

At Least 7 Explosions and Low-Flying Aircraft Are Heard in Venezuela’s Caracas

-

◎竹増ローソン社長インタビュー〔1〕_20251228YGTGS000198_C-250x166.jpg)

Convenience Store Chain Lawson May Start OTC Drug Delivery in 2026

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

BOJ Gov. Ueda: Highly Likely Mechanism for Rising Wages, Prices Will Be Maintained

-

Core Inflation in Tokyo Slows in December but Stays above BOJ Target

-

Osaka-Kansai Expo’s Economic Impact Estimated at ¥3.6 Trillion, Takes Actual Visitor Numbers into Account

-

Japan Govt Adopts Measures to Curb Mega Solar Power Plant Projects Amid Environmental Concerns

-

Japan, U.S. Start Talks on Tokyo’s $550 Bil. Investment in U.S.; Energy, AI Projects Were Focus of 1st Meeting