40 Years After Plaza Accord, Global Trade Imbalances Still a Tough Issue for Nations to Address

Leaders gather for a photo at the G20 Summit held in 2019 in Osaka, where Japan directly raised the issue of global imbalances in an effort to avoid protectionism.

8:00 JST, October 11, 2025

Forty years after the Plaza Accord, the United States, which once led the creation of postwar international economic rules, has now become a country destabilizing the global economic order through U.S. President Donald Trump’s high tariff policies and other measures.

We have now entered a “G-Zero world,” characterized by a leaderless international system, as if it were guided by a Group of Zero rather than the Group of Seven or Group of 20.

Japan must confront the reality of the global economy, which has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past 40 years, and formulate its future economic policies while drawing lessons from the Plaza Accord.

On Sept. 22, 1985, finance ministers and central bank governors from Japan, the United States, West Germany, France and the United Kingdom — countries collectively known as the Group of Five — gathered at New York’s Plaza Hotel and agreed to correct the strong dollar.

The Plaza Accord did achieve remarkable results in terms of correcting the strong dollar. For example, the exchange rate of ¥240 to the dollar had changed to ¥150 a year later.

However, from the perspective of macroeconomic policy coordination, there were shortcomings.

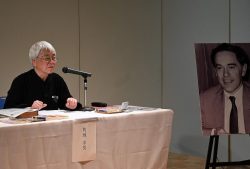

Toyoo Gyoten, a former vice minister of finance for international affairs at the predecessor of the current Finance Ministry, was involved in the agreement as a bureaucrat. He recalled the time, saying, “We focused on exchange rate issues but did not discuss fiscal or monetary policy matters.”

The Plaza Accord failed in its aim to reduce Japan’s current account surplus through the exchange rate adjustments.

Regarding the limitations of the Plaza Accord, it is beneficial to consider the issue from the perspective of “global imbalances.”

Global imbalances refer to worldwide disparities in current account balances. The current account balance is the sum of the trade balance (comprising exports and imports of goods), the services balance (encompassing transfers of services) and investment income, such as interest and dividends.

The balance between savings and investment in a country is deeply linked to its current account balance. If global economic imbalances worsen, it will undermine stable growth.

At the time of the Plaza Accord, typical global imbalances were also emerging.

The United States saw its fiscal deficit widen due to large-scale tax cuts under Reaganomics, while a strong dollar led to an expanding trade deficit. It thus faced twin deficits of fiscal and trade deficits, with its current account balance — including the trade deficit — also in the red.

Borrowing from countries that had a current account surplus, such as Japan and West Germany, helped cover these deficits. This imbalance posed a significant risk to the global economy.

This global imbalance was resolved mainly during the 1990s. But the reason was not that the G5’s macroeconomic policy coordination was successful.

Japan’s reliance on monetary easing as a policy to stimulate domestic demand became one of the root causes of the bubble economy, and the subsequent collapse of that bubble weakened the Japanese economy.

Meanwhile, the United States rode the wave of the IT revolution to achieve a resurgence.

The reversal of the Japan-U.S. economic dynamic, correcting the imbalance, was an ironic outcome for Japan.

Looking back now, Gyoten said, “The export-driven Japanese economy should have been transformed into an economic structure less susceptible to the impact of drastic yen fluctuations.”

Around the 2000s, global imbalances once again began to be highlighted as a risk to the world economy amid China’s rise and the advancement of globalization.

The 2008 financial crisis was a significant disruption caused by these imbalances.

At that time, the United States engaged in excessive consumption, while China flooded it with exports. The U.S. current account deficit reached an unprecedented 6.0% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2006, while China recorded a current account surplus of 10.6% in 2007.

The subprime mortgage crisis was attributed to a proliferation of securitized products, developing into a situation that eventually burst.

After the crisis, the United States actively moved to correct the strong dollar in 2010 in a more sophisticated way. This time, the target was China, not Japan.

In October 2010, at the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting held in South Korea, the United States suddenly proposed measures to correct global imbalances with little prior explanation.

The proposal called on countries to limit their current account deficits or surpluses to within 4% of their GDP by 2015.

For a country to reduce its current account surplus, it must reduce its trade surplus, either by appreciating its currency or by expanding domestic consumption.

The United States’ ostensible target was the current account balance. Still, it was clear that the real goal was to force a revaluation of the renminbi, as it was known to be difficult for export-driven China to expand its domestic demand.

However, each country faces its own domestic challenges, making the coordination of macroeconomic policies difficult.

Germany, a country with a current account surplus, opposed the move, wary of restrictions on its economic policies, and Japan also adopted a cautious stance. The U.S. strategy failed.

Regarding Japan’s efforts, I would like to highlight a case from 2019. Japan directly raised the issue of global imbalances at the G20 summit held in Osaka.

The International Monetary Fund had sounded the alarm in reports analyzing 30 major countries and regions in the summer of 2018, stating that “global current account imbalances have become entrenched, fueling protectionist sentiments.”

Japan’s approach to avoiding the deepening of protectionism lay in understanding the issue of imbalance.

Japan’s prescription for all countries is to undertake structural reforms across three sectors — households, businesses and government — to prevent excessive surpluses or deficits from occurring.

For example, some countries with current account surpluses have excessive household savings due to concerns about their social security systems.

Advancing social security reforms to provide greater security in old age would reduce excessive savings and consequently lower the current account surplus.

In contrast, the United States needs to correct excessive household consumption and insufficient savings.

Japan’s approach was constructive in content, but it failed to translate into concrete measures to mobilize other countries, and thus it ultimately fell short of its objectives.

Now the global economy is far from balanced.

Amid this situation, Trump, in his second term, has viewed the outflow of manufacturing due to a strong dollar and the normalization of trade deficits as problems, attempting to bring manufacturing back to U.S. shores through high tariff policies.

If trade deficits fail to shrink as anticipated, he may even consider correcting the strong dollar. A “Mar-a-Lago Agreement,” proposed by an economist close to Trump, is also drawing attention.

During the Trump era, the approach will likely involve unilaterally imposing “policy agreements” rather than reaching consensus through policy coordination. Since China rejects easy compromises, achieving an agreement akin to the Plaza Accord is unrealistic.

Other countries, including Japan, will need to formulate strategies anticipating that current U.S. foreign policy will persist for the long term.

Takeshi Makita, chief senior economist at The Japan Research Institute, notes that countries and regions like Japan should seize the opportunity presented by external pressure from the U.S. tariff policies to undertake fundamental reforms of their economic structures.

Indeed, it is undesirable that advanced, emerging, and developing countries, including Japan, are striving to export to the U.S. market while failing to advance their own policies to promote domestic demand.

It is necessary to increase per capita GDP growth through measures such as strategic domestic investment promoting the digital transformation, which can raise Japan’s potential growth rate.

Japan will likely need to strengthen its growth strategy, expand domestic demand and enhance market linkages with Europe, Asia and Africa.

Trump views trade deficits as bad.

A trade deficit or current account deficit is not necessarily bad, nor is a surplus necessarily good. The problem lies in the inability to control the expansion of trade deficits and current account deficits.

Balance is the essence of it all.

The lack of hope that Trump will come to such a conclusion is a tragedy.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Akihiro Okada

Akihiro Okada is a vice chairman of the editorial board for The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

Flu Cases Surging Again: Infection Can Also Be Prevented by Humidifying Indoor Spaces

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review