Data Centers Slurp Up Water to Keep Servers Cool; Essential Infrastructure Has Environmental Impact

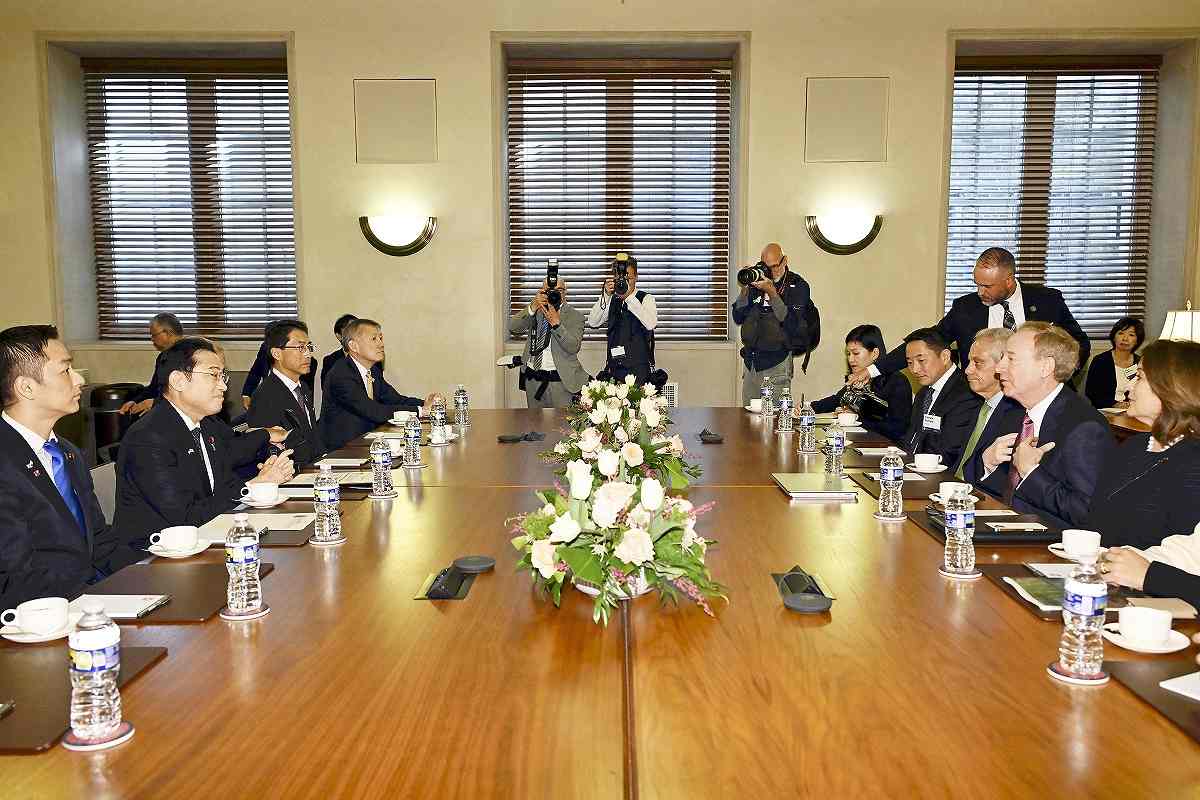

A meeting in Washington in April at which Microsoft President Brad Smith told Prime Minister Fumio Kishida about the company’s investment plans in Japan, including data center construction.

8:00 JST, July 20, 2024

In 2023, humanity experienced the hottest summer in history. United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres expressed his sense of crisis: “The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.” The threat to human survival from climate change has become an immediate crisis. Along with efforts toward decarbonization, a new challenge has emerged: addressing the “water problem” associated with the advancement of digitization. In the background is the construction of data centers, which are expanding rapidly worldwide.

Digital data is the foundation for all modern services, from education to healthcare. Demand for digital services will continue to grow as generative artificial intelligence gains momentum. The critical infrastructure at the core of this digital age is the data center, a large building specially constructed to house servers and network equipment.

A typical data center has all the facilities necessary for server installation, including high-speed lines for connection to the internet and other external networks, cooling equipment and a large-capacity power supply. The building is earthquake-resistant and seismically isolated, and access is protected by tight security measures, including ID cards and biometric authentication. In case of fire, nitrogen and carbon dioxide will be used instead of water. Together, all of these measures protect the servers from damage.

Data centers have become a huge industry, especially for tech companies, as the race to develop generative AI, which requires enormous computing power, intensifies worldwide. In the United States, Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft and other companies have built data centers in various locations.

As with government-subsidized semiconductor plants, there is a rush to build them, and hopes are high that they will replace auto plants and other manufacturing industries as a source of employment. Since the construction of data centers creates jobs, the U.S. administration is promoting their economic benefits in battleground areas for this year’s presidential election as well as using them to seek an edge in the heated international competition in AI-related industries.

Similarly, there has been an active movement in Japan to build data centers and secure sites for them. Until now, most data centers have been built in commercial and industrial areas around the Tokyo metropolitan area because of the ease of securing high-voltage power and the proximity to demand areas.

However, from the standpoints of information security, disaster prevention and power security, the current concentration of many data centers in the suburbs of Tokyo must be called a national risk. This is why construction is expanding into the Kansai area, focusing on hyperscale data centers capable of efficiently processing larger volumes of data.

For example, Sharp Corp. announced plans in June for the site of its Sakai Plant, which was one of the world’s largest and most advanced LCD panel factories when it was completed in 2009. Sharp, which has dominated the global market with its Aquos brand LCD TVs, will shut the plant down by the end of September and use the site as a data center. SoftBank, KDDI and other companies are expected to participate in the project.

The scope of data center construction sites is also expanding to regional cities, partly to secure backup functions in the event of disasters for the sake of urban resilience, and partly due to the government’s policy of decentralization.

In Inzai, Chiba Prefecture, significant businesses such as Google and Equinix have built data centers. The mayor of Inzai said that compared to logistics facilities, data centers are subject to significantly higher property taxes. In addition to the buildings themselves, servers and other IT equipment are subject to property taxation. The abundance of land in semi-industrial zones and other areas where development is easy also boosted the project.

In 2023, Asa LLC secured more than 270,000 square meters of land in Mihara, Hiroshima Prefecture, and 370,000 square meters in Wakayama City. Google has not officially announced this, but according to city officials, Asa LLC is a Google Group company, and the data centers will be built on both sites.

Generative AI, which involves considerable computation, consumes much power and requires a large server farm to provide sufficient data to train its programs. Robust cooling systems are essential for the data centers responsible for this. Generally, the air conditioning in the server room is set between 18 C and 27 C. Because the servers generate heat, not to mention the effects of outside temperatures, many use evaporative cooling systems as an efficient cooling method. This requires much water.

Researchers from the University of California and other institutions estimate that the average data center requires one gallon of water for every kilowatt-hour of electricity used. It is also essential that clean, fresh water be used in data centers to prevent the corrosion of equipment and the proliferation of bacteria. Seawater or dirty water is not acceptable. According to Google’s sustainability data, approximately 20 data centers consumed a total of about 5.2 billion gallons of water in 2022, or 14 million gallons daily. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that this is equivalent to the consumption of approximately 175,000 individual Americans.

It is estimated that the entire training of OpenAI’s generative AI, GPT-3, took the equivalent of several hundred years of electricity for a typical U.S. household and required 700,000 liters of cooling water. And for every 20 to 50 questions GPT-3 is asked, it “drinks” another 500 milliliters of water. Furthermore, the amount of water required increases with each new model.

According to the World Economic Forum, 44 million people in the United States already have unstable water supply systems. Stanford University predicts that by 2071, about half of the 204 freshwater basins in the U.S. will be unable to meet monthly water demand, and water supplies in many areas could be reduced by as much as one-third.

The competition for data center expansion is fierce, and there are some questions about whether the best choice for the environment will always be made. Last year in Uruguay, Google faced massive opposition to the construction of a data center even though such facilities use far less water than do pulp and paper, which are the primary industries in the country. Construction will increase, and water demand will continue to grow, potentially exacerbating water shortages. In Japan, AI is also expected to help solve pressing issues such as an aging workforce and growing medical needs. Data centers that provide a secure and stable base for data and system operations are indispensable for Japanese companies to increase productivity and create high-value-added products.

The concept of “carbon neutrality” has become widely known to the public as government and industry leaders worldwide have announced their goal of achieving zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, the concept of “water neutrality” — ultimately reducing the impact of business activities on water resources, such as water withdrawal and wastewater discharge, to zero — is not so well recognized. In the future, this concept will play an increasingly important role in international business and policy discussions. AI development and environmental conservation will be required to reduce AI water consumption and promote environmentally friendly development. The entities involved also have a responsibility to make information publicly available to ensure transparency.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Shingo Sugime

Shingo Sugime is a staff writer in the Economic News Department of The Yomiuri Shimbun Osaka.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan