Akama-suzuri inkstones such as a stylish oval-shaped inkstone, right front, and a traditional inkstone, left

13:22 JST, July 30, 2024

YAMAGUCHI — A reddish-brown stone is chipped away by a chisel, little by little. The large handle digs into the shoulder of a craftsman as he puts his weight against it.

The workshop of Yoichi Hieda, an Akama-suzuri craftsman, lies in a village in a valley in Ube, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Akama-suzuri, or Akama inkstone, is made from a kind of red shale called Akama stone extracted from a nearby quarry. Boasting a history of more than 800 years in production, the inkstones have been treasured by many for their ability to help produce smooth sumi liquid ink.

Akama-suzuri is said to have been presented as an offering by Kamakura period (late 12th to 1333) shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo to the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, at the beginning of the era. Inkstone production is believed to have begun as early as the end of the 12th century.

The term Akama-suzuri appears in a document written in the early Edo period (1603-1867). The Akama inkstone used by Yoshida Shoin, a prominent Japanese intellectual from the late Edo period, is now housed in Shoin Shrine in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, as the shrine’s goshintai, or object of worship.

The name of Akama-suzuri has its origin in Akamagaseki, present-day Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, which had been produced there. When people began quarrying in Ube during the Edo period, the inkstones were produced in both cities.

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), at the peak of production, nearly 300 craftsmen produced Akama inkstones. Today, the number of such craftsmen has dwindled down to only six in these cities. Of them, only Hieda and two other artisans in Ube consistently do the entire production process from quarrying to polishing. Hieda, the fourth-generation owner of the factory, has been learning from his father, Toshio, to hone his skills since 2002.

Top:Yoichi Hieda forcefully carves a chunk of Akama stone.Bottom:Chisels with handles adjusted by Hieda to fit his body

Hieda is also a researcher: when he was a graduate school student, he chose the Akama inkstones as his dissertation topic at a time when records documenting them were scarce. Hieda examined the surface of the inkstone and components of raw Akama stone. As a result, he found out why the Akama inkstones had been harshly criticized as being “impossible to grind [sumi ink on]” for a certain period after World War II: artificial whetstones had been used in the process of polishing the inkstones, instead of natural ones.

He also proved that the particles which make up raw Akama stone are so tightly packed that the particles of sumi liquid ink produced by the inkstone are very small.

Ink from Akama inkstones is suited for writing kana characters and drawing ink brush paintings. Hieda made the inkstones lighter in weight by carving them into an oval shape to help the many women who do this kind of calligraphy. The lighter inkstones became a favorite of consumers and he says they are so popular now that production cannot keep up with the demand.

What concerns him most now is the issue of successors: “I would like to create an environment where successors can obtain a stable income when they become independent,” Hieda said. In order to achieve that, he has been making various efforts, such as using powders produced when carving inkstones as glaze for ceramics and developing bracelets using Akama stones.

“I would like to increase the number of people ‘doing sumi ink things.’ For that purpose, I’d like to continue producing authentic inkstones that could move people’s hearts,” he said.

Top Articles in Culture

-

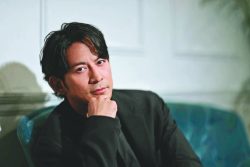

Junichi Okada Wears Three Hats in ‘Last Samurai Standing,’ Serving as Star, Producer, Action Choreographer in Thrilling Netflix Period Drama

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Maison&Objet Kicks off Near Paris with Japanese Lighting Designers’ Installations on Display, Creating Rich Environment

-

Prestigious Japanese Literature Prize Names Toriyama, Hatakeyama as Winners

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time