Then Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda apologizes to members of his Democratic Party of Japan after its disastrous defeat in the lower house election on Dec. 19, 2012.

8:28 JST, January 14, 2023

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), founder of the Edo shogunate, is the man of 2023 in Japan. Ieyasu’s reign is the subject of a taiga historical epic drama series that just started airing on NHK. Ieyasu spent a long time out of power before becoming one of the most powerful figures in Japanese history — his life may have an important lesson to offer today’s opposition parties, who themselves have been out power for many years.

Today’s world, like the one Ieyasu lived in, is indeed a tough place. With no clear end to the COVID pandemic in sight, Russia’s continuing invasion of Ukraine, persistent high prices and economic hardships, uncertainty and anxiety define the world we live in. Ieyasu survived his own turbulent times using patience, perseverance and cleverness as his weapons. The government he established would maintain peace in Japan throughout the 260-year Edo period.

Ieyasu, far from a dusty relic, is creating a buzz in present-day political circles. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida revealed in a Jan. 1 interview that he was very fond of Ieyasu when he was younger. Natsuo Yamaguchi, the leader of Komeito, the junior party in Japan’s ruling coalition, also discussed Ieyasu on the party’s website.

Among opposition parties, Yoshihiko Noda, the last of three prime ministers from the 2009-12 period when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was in power, also mentioned Ieyasu on his own blog. After praising Ieyasu’s patience and gradualism, Noda reflected on his own time as prime minister and wrote that he did not have enough patience. It is not hard to imagine that Noda’s comment is about the DPJ itself, which attempted radical change of the Japanese social system, only to fall apart after repeated intraparty conflicts.

Looking back, 10 years have passed since December 2012, when the DPJ, led by Noda, suffered a disastrous defeat in the lower house election and power returned to the hands of the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party. It would be no exaggeration to say that the past decade has been a period of rock bottom for Japan’s opposition parties.

The DPJ, which had lost the public’s trust, was unable to break out of the doldrums and resorted to a cosmetic name change. The party finally split into a conservative-leaning party and a liberal one ahead of the 2017 lower house election, with the liberal offshoot calling itself the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ). The two sides merged again in 2020 to form a new party under the CDPJ name, although some former DPJ-affiliated forces have become the Democratic Party for the People, which has center-right policies that they are trying to realize by working with the LDP.

Meanwhile, Nippon Ishin no Kai (Japan Innovation Party), originally formed as a regional party in 2010 by local lawmakers who left the LDP, continues to expand its power, taking advantage of the weakening of the erstwhile DPJ-affiliated forces. Smaller parties with their own policies are also in disarray. This weakened state of the opposition parties is a far cry from the two-party system that has been the political ideal since the 1996 launch of the single-seat constituency system. The long rule of the LDP is also the result of the fecklessness of the opposition parties themselves, which have been impatiently splitting into smaller forces without a clear policy counterpoint.

There were signs of change in last year’s extraordinary Diet session. The CDPJ, now the leading opposition party, and Ishin no Kai, the second opposition party, started cooperating in the Diet. The successful collaboration between the two parties proved that opposition parties have the power to sway the government and ruling parties if they work together, as evidenced by the fact that they were the driving force behind the speedy passage of a bill intended to prevent damage from unscrupulous solicitations for large donations by groups such as the Unification Church. The two parties will also likely “fight together” in the ordinary Diet session to be convened in late January. The CDPJ hopes to develop the relationship between the two parties to include electoral cooperation and, in the future, to establish a coalition government.

Yet the hurdles ahead for the opposition parties are high. That is, there is a big gap in the fundamental policies of the two major opposition parties. Their positions on constitutional reform and security policies differ greatly. Although the CDPJ has its origins in the DPJ, it is considerably more liberal and idealistic in its policies than the DPJ was. Regarding Japan’s possession of “counterattack capabilities” to target enemy missile launch sites and other facilities for the purpose of self-defense, which was included in the revision in December of Japan’s three key national security and defense documents, the CDPJ leadership tried to unite the party in accepting the counterattack capabilities as a way to demonstrate the party’s realistic policies. However, the leftist and liberal factions opposed it, forcing the party to withhold its acceptance. In contrast, Ishin no Kai’s security policy does not greatly differ from that of the LDP. It accepts the possession of “counterattack capabilities.”

However, even if not considering the element of cooperation with Ishin no Kai, it is important for the CDPJ to take a pragmatic course if it aims to take power from the LDP. According to a 2021 joint survey by The Yomiuri Shimbun and Waseda University, 82% of respondents said Japan needs an opposition party that can stand up to the LDP. In the Yomiuri-Waseda joint survey conducted in 2022, 74% of respondents agreed that “Japan’s defense capability should be further strengthened” and 75% were also in favor of an amendment to enshrine the Self-Defense Forces in Article 9 of the Constitution.

Although the public yearns for a reliable and trustworthy alternative to the LDP, they are not looking for extreme policy changes, particularly regarding diplomacy and security, the foundational elements of statecraft. Yukio Hatoyama, the first of the three DPJ prime ministers, sought drastic policy changes in foreign and security policies, which damaged Japan’s relationship with its ally, the United States. Above all, it caused unease among the public and raised questions about the DPJ’s ability to govern the country.

The security environment surrounding Japan has become increasingly severe over the past decade. North Korea has become incredibly provocative, and China has been building up its military power with no effort to hide its ambition to change the rules-based order. Russia, which invaded Ukraine, is also a neighbor to Japan. Some leftist members of the CDPJ are convinced that a Taiwan contingency will not happen, but how can they be so certain? Instead of reflexively pursuing policies that differ greatly from those of the LDP, CDPJ should be patiently working to steer the party back to realistic policies. The voters have already realized that wishful pacifism will not protect the nation.

Ieyasu is famous for many sayings, the best-known of which is “If a bird does not sing, [I will] wait for it to sing.” This quote is considered a testament to Ieyasu’s patience, and the Japanese people value patience. However, the opposition parties have not sung in 10 years — and the patience of the Japanese public is wearing thin.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Yuko Mukai

Yuko Mukai is a staff writer in the Political News Department of The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

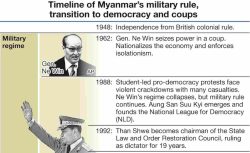

Myanmar Will Continue Under Military Rule Even After Election, Ex-Ambassador Maruyama Says in Exclusive Interview

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

Expansion of New NISA: Devise Ways to Build up Household Assets

-

China Criticizes Sanae Takaichi, but China Itself Is to Blame for Worsening Relations with Japan

-

Withdrawal from International Organizations: U.S. Makes High-handed Move that Undermines Multilateral Cooperation

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time