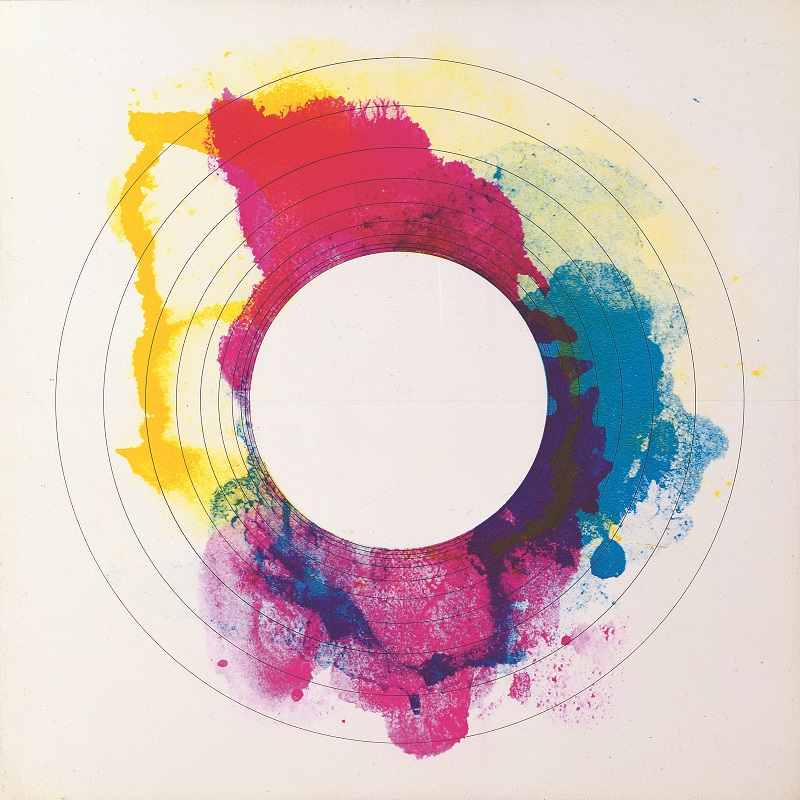

The score for “Corona II for Strings” by Toru Takemitsu (in possession of Schott Music Co. Ltd.)

17:45 JST, September 9, 2021

The primary colors, red, blue and yellow, splashed across concentric circles, overlap at times. At first, it may look like the colors were just thrown on top of each other, but they were actually printed on separate sheets of plastic. When the sheets are rotated around the center, the shapes and hues change.

Although it looks like a piece of abstract art, this is a musical score jointly produced by composer Toru Takemitsu (1930-96) and graphic designer Kohei Sugiura. The title is “Corona II for Strings.”

“It’s an etude for grasping a note as something that is fulfilling and brimming with life,” Takemitsu once said in explaining the word “corona,” which is the ring of light from the sun that can be seen during a total solar eclipse.

That said, there are probably no musicians who can play this just by looking at the colors, so the published score includes written instructions for the performers. First published as a supplement to a special issue of the fine art periodical Bijutsu Techo in 1962, this is a work in which a designer used colors and shapes to make a physical image of the sounds created by the composer.

“The colors that make up the corona, which shift and change in appearance, represent the sounds that mix together and resonate through the air,” said musicologist Mitsuko Ono, a specialist on Takemitsu’s music. “Takemitsu could probably be inspired by the image’s fluidity and hear the sound it could produce. I think he was a composer with a rare ability. His creativity was deeply rooted in his ability to connect music and visual art.”

Birth of a legend

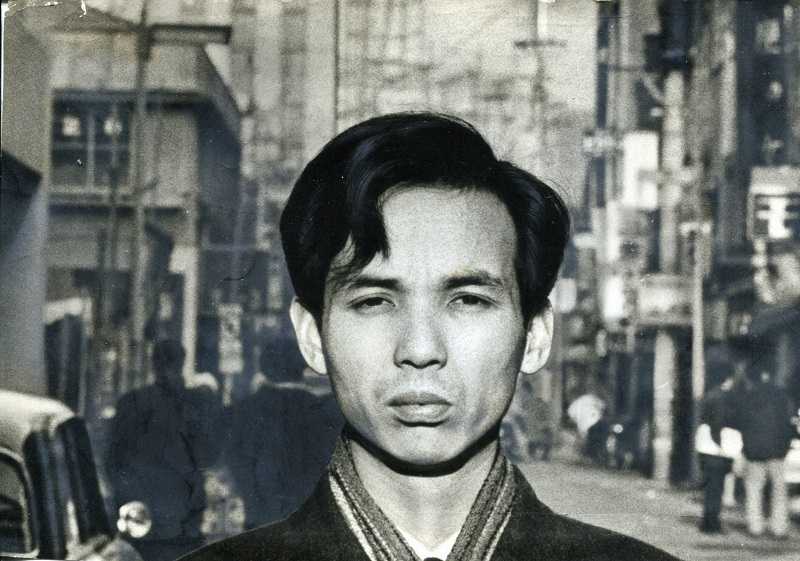

Toru Takemitsu was introduced as one of “the faces of today” in The Yomiuri Shimbun in January 1960.

Tokyo native Takemitsu was largely self-taught. He started garnering attention in 1957 with “Requiem for Strings” and won international acclaim with “November Steps” in 1967. He composed film scores and pop songs, and also served as the producer and supervisor for Music Today, a contemporary music festival that he started.

Takemitsu was the leader of the composition scene in postwar Japan, and published many books containing his essays.

Poet and art critic Shuzo Takiguchi (1903-79) was someone Takemitsu considered a mentor. Young artists and composers who were associated with Takiguchi formed an experimental art group called Jikken Kobo (1951-57). As a member of the group, Takemitsu composed nontraditional music. What he later described as “the good fortune of meeting friends whom I could compete with and inspire” became a major factor in the birth of Takemitsu the composer.

“What we call the coexistence of different personalities is a contradiction that does not logically hold up,” Takemitsu later wrote in his book “Oto: Chinmoku to hakariaeru hodo ni” (Sounds: So that they can measure up to silence) regarding the friendly competition. “I didn’t try to overcome that contradiction by attempting to work on joint projects.”

When Takemitsu was working on “Corona II for Strings,” he was also coproducing “Corona for Pianist(s)” with Sugiura.

“It’s not like we always had matching opinions. That’s exactly why our work was ours individually,” Takemitsu said.

Takemitsu also loved visual art. He would paint and write critiques of his favorite works. However, when it came to improving his musical compositions, he tried to get inspiration from art that was very different from his own. This is an example of the “contradiction” that was Takemitsu’s driving force.

Blending contradictions

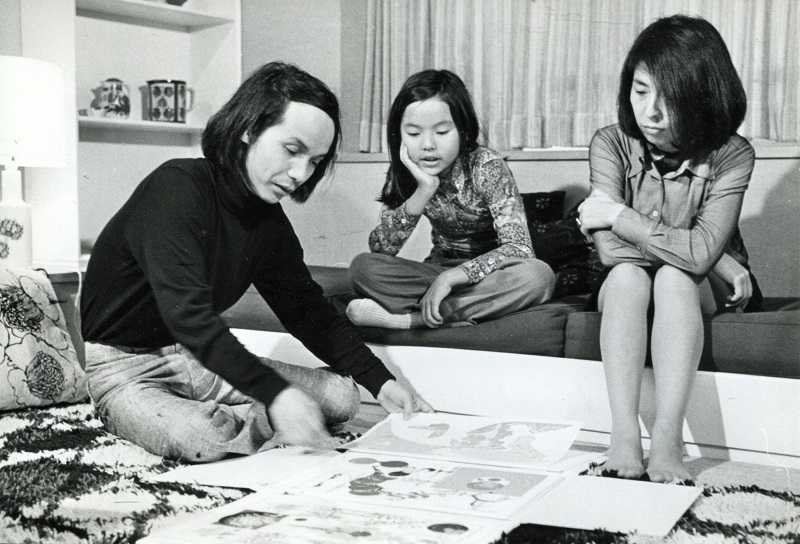

“He liked looking at art as well as drawing,” said Maki Takemitsu, 59, about her composer father. “He drew distinctive lines and was particular about the colors he used. He bought me an eye shadow palette as a souvenir from abroad. He was a fan of colorful things.”

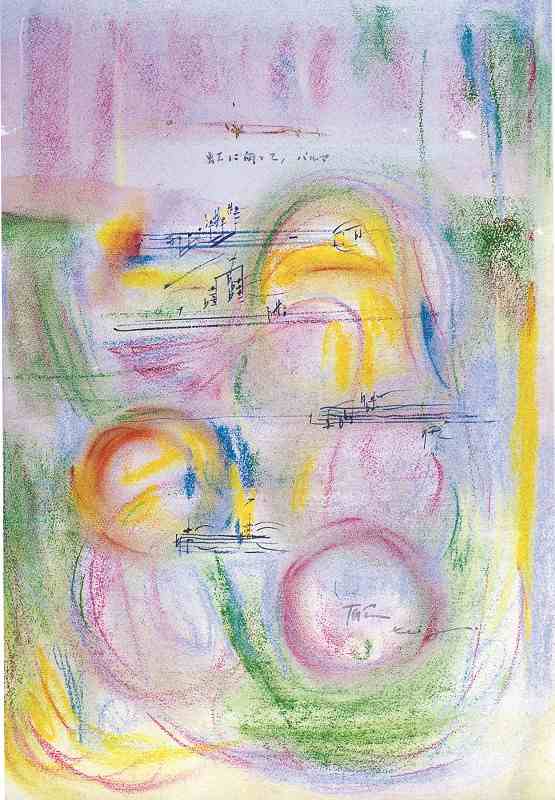

“Vers, l’arc-en-ciel, Palma — hommage a Joan Miro” is an art piece cocreated by Takemitsu and painter Keiji Usami (1940-2012), based on the composer’s orchestral work “Vers, l’arc-en-ciel, Palma.” The piece was created as an homage to one of their favorite Spanish painters. Takemitsu drew musical notes and Usami added the colors, bridging the two art forms and seemingly blending the “contradictions.”

“Vers, l’arc-en-ciel, Palma — hommage a Joan Miro” (1984) by Toru Takemitsu and Keiji Usami (part of a private collection)

One of the artists Takemitsu loved was printmaker-artist Mitsuo Kano, now 88, who was three years his junior. In 1969, Takemitsu asked Kano to design the cover art for an album. Kano chose to use his own three-dimensional work “Planet Box — Hibiki to Ryushi” (Planet box — resonance and particles).

“Aren’t the red and yellow incredibly vivid?” Kano said about the cover. “I didn’t understand Mr. Takemitsu’s music very well, but around the same time, I had started making objects and wanted to try something new.”

Instead of creating something that matched the music, the artist threw quite a different image at him. Takemitsu must have been elated to receive such a work from Kano.

The cover of a record album, featuring music by Toru Takemitsu, designed by Mitsuo Kano

Understanding the ‘stranger’

Members of Jikken Kobo included pianist Takahiro Sonoda (1928-2004), music critic Kuniharu Akiyama (1929-96) and composer Joji Yuasa, who was a year older than Takemitsu.

“Everyone had a strong personality, so we argued a lot,” said Yuasa, looking back. “But we didn’t have a bad influence on each other.”

Yuasa thinks there was a separation between Takemitsu’s taste in art and the images in his mind.

“I don’t quite understand the relationship between Takemitsu’s visual images and his music,” Yuasa said. “But the same can be said about the relationship between his writing and music.”

Motoaki Hori, 60, the chief curator of Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, was in charge of “Toru Takemitsu / Visions in Time,” an exhibition on Takemitsu in 2006.

“Joint productions across genres require a relationship based on trust and respect,” Hori said. “Jikken Kobo [members] had that relationship because they came of age in an era when there was a fervor for new art during the postwar years.”

Takemitsu’s open-mindedness can be attributed to his years in the group.

Many people associate Takemitsu’s art, which has a serene quality, to being surrounded by nature. However, his daughter does not agree.

“My father loved the bright lights of the neon forest in Tokyo as much as he loved the actual forests near our vacation home in Miyota, Nagano Prefecture,” she said.

Takemitsu embraced contradictory elements within himself and sought the same thing from his relationships as well. To the composer, art may have been an irreplaceable “stranger” within himself.

Toru Takemitsu, left, his daughter Maki, center, and his wife Asaka look at a collection of prints around 1970.

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan