Reviews of Foreign Investment in Japan: Utilize New Government Body to Prevent Leaks of Sensitive Technology

15:56 JST, January 26, 2026

Preventing leaks of sensitive technology has become increasingly important for national security. The government must urgently expand and improve the system for reviewing foreign investments.

An expert panel of the Finance Ministry has compiled a report that calls for more stringent screenings of foreign investments in Japanese companies. The panel states that a system that works across multiple ministries and agencies is desirable for conducting reviews in cooperation with security-related government entities.

In the United States, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which involves government bodies such as the Treasury Department and the Defense Department, reviews planned foreign investments. Japan intends to establish a Japanese version of CFIUS with this framework in mind.

Countries and regions are competing fiercely over technological development in such areas as artificial intelligence, semiconductors and quantum technology. As dual-use technologies that can be used for both military and industrial purposes proliferate, preventing leaks has become an urgent task. From an economic security perspective, it is reasonable to strengthen the investment screening system.

Japan’s reviews of foreign investments are currently handled by the Finance Ministry and other entities, based on the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law. The law requires prior notification when foreign investors plan to acquire 1% or more of shares in a listed company in sectors critical to security, such as nuclear power, energy and telecommunications.

If problems are found with the investment during reviews, the authorities can recommend or order that it be halted.

Japan’s challenge lies in its weak intelligence capabilities. There are many cases where the sources of funding for foreign investments are not clear.

Despite the need for intelligence organizations and police to work together for reviews, some argue that information sharing is insufficient due to deep sectionalism among ministries and agencies. In fact, only one investment plan has been ordered to be halted in the past.

In the United States, CFIUS has primarily blocked acquisitions by companies linked to China. In 2024, it ordered a company believed to be Chinese-affiliated to sell a cryptocurrency-related facility near a U.S. military base.

If a Japanese version of CFIUS is established, it could facilitate the sharing of sensitive information among ministries and agencies and enable rigorous screenings. The body should also cooperate with a national intelligence bureau, which the government is considering setting up to serve as an intelligence command center. Future expansion of the personnel and organizational structure will be also essential for the foreign investment watchdog.

The government should balance this initiative with its growth strategy. The outstanding balance of foreign direct investment in Japan at the end of 2024 exceeded ¥50 trillion, which is extremely low compared to other major countries, given the scale of Japan’s economy. The government aims to boost the figure to ¥120 trillion by 2030.

When strengthening the investment screening system, it is crucial to accurately identify investments that raise concerns, to prevent the system from discouraging foreign investors.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Jan. 26, 2026)

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

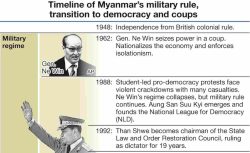

Myanmar Will Continue Under Military Rule Even After Election, Ex-Ambassador Maruyama Says in Exclusive Interview

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

Expansion of New NISA: Devise Ways to Build up Household Assets

-

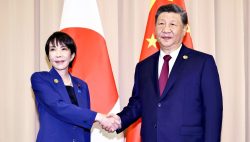

China Criticizes Sanae Takaichi, but China Itself Is to Blame for Worsening Relations with Japan

-

Withdrawal from International Organizations: U.S. Makes High-handed Move that Undermines Multilateral Cooperation

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time