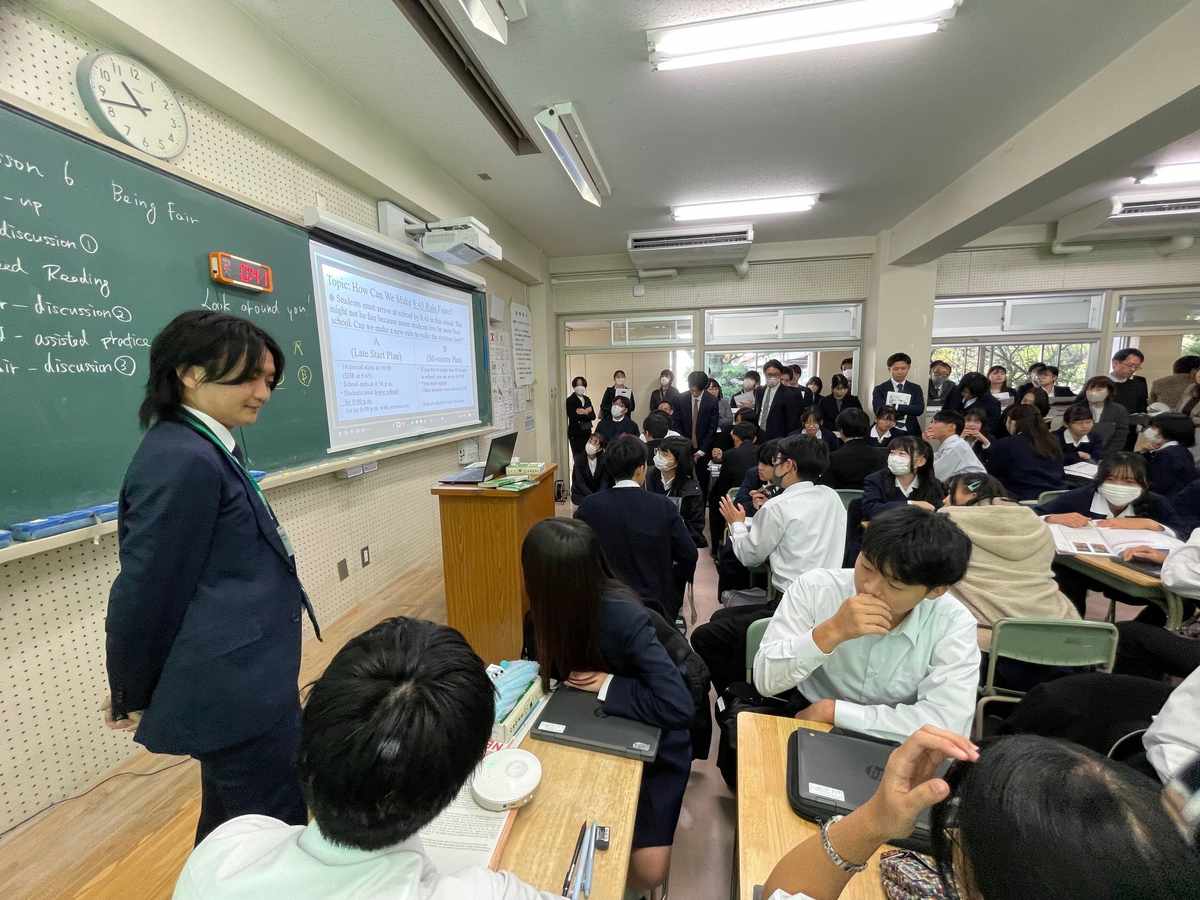

Ninth-grade students at Hiroshima University High School engage in pair discussions in English on Nov. 21 during a class in which they also used AI.

8:00 JST, December 20, 2025

AI translation has made significant strides in recent years, now handling tasks once considered uniquely human, such as translating manga and literary works, and providing simultaneous interpretation at international conferences. Schools have also begun introducing apps that correct English compositions and evaluate pronunciation. AI is rapidly becoming more significant to the learning of foreign languages and the ways they are taught.

Technology developed by manga-translation company Mantra symbolizes this shift. “To begin with, we upload the image data of an entire manga chapter to a computer — images in which Japanese text appears inside speech balloons,” explained Mantra’s Chief Technology Officer Ryota Hinami, 34. The system uses a process called optical character recognition to extract the text and then runs it through AI translation, after which professional human translators revise the output. Edited translation data are accumulated and reused to maintain consistent tone and terminology.

CEO Shonosuke Ishiwatari, 33, describes the core of their technology as follows: “A major feature of our system is that it automatically infers a list of character names from the images the AI reads, identifies who appears in each panel, and estimates which character each speech balloon belongs to.” This makes it possible to produce translations that reflect the personality of each character, driving a surge in demand. Over the past year, the number of pages processed per month has grown from 100,000 to 200,000, and Mantra’s work now extends to novels, anime and games. “In entertainment translation, preserving each character’s authenticity is crucial. The strengths we developed in manga translation apply directly to that,” Ishiwatari said.

Underlying this growth is the rapid global expansion of Japan’s content industries — games, anime and manga. With the spread of video streaming services, simultaneous worldwide releases have become commonplace, and hit titles are distributed in dozens of countries. Publishers, animation studios and game developers now plan for overseas markets from the outset, making translation speed and quality decisive business factors. This rising demand is fueling the development of entertainment-focused translation technologies like Mantra’s.

Google Translate launched in 2016, followed by DeepL in 2017. Both are forms of neural machine translation, which mimics the neural circuits of the human brain and learns from vast repositories of translation data. Soon after their debut, they reached a proficiency level comparable to a TOEIC English exam score in the 900s, and today they deliver output approaching professional quality.

However, they have a notable weakness: difficulty capturing context, making them poor at translating novels and similarly complex texts. Then, in 2022, generative AI — such as ChatGPT, which excels at contextual tasks — entered the scene.

According to Eiichiro Sumita, a fellow at the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology and a leading authority on AI translation, anime translation now achieves high accuracy when scripts or entire subtitle datasets are provided as input. “The system can recognize who is speaking, in what scene, and what relationship they have,” he said. For Japanese-to-English translation, experiment results show that “97% of the output is semantically accurate.”

Manga translation is even more difficult, but improvements in generative AI’s image-recognition capabilities have brought the technology to a point where it can produce sufficiently high-quality translations.

“While generative AI clearly wins in context processing, “neural translation” remains overwhelmingly superior in processing speed and cost. That’s why neural translation is still the mainstream for simultaneous interpreting,” Sumita said. Indeed, when tech events are held at well-equipped facilities, it is no longer unusual to see simultaneous AI transcriptions and translations of English talks displayed in both Japanese and English on screens flanking the stage.

Meanwhile, AI is gaining a strong presence in education. At Hiroshima University High School in Fukuyama, Hiroshima Prefecture, a model school under an initiative of the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry to strengthen English education through AI, teachers are proactively incorporating AI into their lessons. In open classes held in late November, AI-supported conversation practice drew particular attention.

In a ninth-grade English class, students discussed which of two proposed school starting-time plans would be fairer. After first exchanging ideas in pairs, they speed-read a 400-word text to gather new information and then reconstruct their arguments. At this point, teacher Kazuya Manago, 30, prompted them: “To make the discussion even better, you have 10 minutes to work with AI.” The interaction with the AI took place through text-based chat rather than spoken conversation, and in the quiet classroom, the only sound was the students’ keyboards clicking.

On each student’s device, the AI program asks, “Which position do you want to take?” One student types, “I think the late-start plan is better,” while another writes, “I believe school should have the same rule for all students.” Through dialogue with the AI, they clarify their positions. Acting as a highly proficient “linguistic expert,” the AI encourages summarization and counterarguments, raising the quality of the practice. As a result, students increased their amount of speech in each pair-work turn, and the range of expressions they used to summarize their partner’s remarks also expanded.

AI is also used to create teaching materials. Manago generated both the speed-reading text used that day and a comprehension quiz for it by specifying vocabulary levels and themes to the AI. “You can summarize an existing text or ask the AI to write from scratch. Because it has become easy to obtain materials tailored to the purpose of each lesson, I now spend more time thinking about what kinds of activities to have students engage in,” he said. After strengthening their skills with AI, students always confirm their learning through human-to-human interaction. The lesson progresses briskly, with students taking active ownership of learning.

AI is also playing an active role in learning at home. In a first-year junior high activity called “AI diary using the past tense,” students interact with AI at home, which asks them about the day’s events and corrects grammatical errors. The following day, during small-talk activities with a neighboring classmate, students review by beginning with “Yesterday, I…” This carries what they wrote in the diary over into speaking practice.

“Using AI at home connects organically with the language activities in class,” said Tomohiro Mochida, 33, head of the English department. “By making use of AI, we can provide each student with specific feedback and tasks. It not only improves efficiency but also brings about a qualitative shift in learning goals.”

AI-supported learning is also practiced at Yokohama Soei Junior and Senior High School, a private school in Yokohama. At the junior high school, two of the four hours of English taught each week are designated as “free learning time,” during which students can choose how they learn. There is a room where Japanese teachers provide instruction, a room taught by native English-speaking teachers, a space for peer teaching, a room for independent study, a room for conversational English, and a room where students learn programming in English.

During this time, some students choose to use AI when they freely select topics and methods of study in spaces such as the peer learning room or the independent study room. This AI is called Weblio Study, a comprehensive English learning application package for schools. It enables consistent training in all four skills — listening, reading, speaking and writing — along with Eiken test preparation, at each student’s own pace.

One activity introduced during these sessions has mixed-grade groups working on themes such as writing texts that recommend Japanese souvenirs or tourist attractions to foreign visitors.

Second-year junior high school student Momoka Uehara said, “AI gives me advice like, ‘Your pronunciation is worth 80 points,’ or ‘If you revise this sentence like this, it will be easier to understand.’” How students proceed is left up to them, and whether to use AI at all is entirely their own choice.

Vice Principal Takao Yamamoto, 55, described the change: “In the past, many students created speeches by imitating textbook passages. Now they can write English that fits their own level and read it aloud with correct pronunciation.”

In a 10th-grade Communication English class taught by Nozomi Wakao, 44, one student spent the summer vacation completing a 30-day independent assignment: writing a daily diary, having it corrected by Weblio, revising the marked parts and compiling newly learned vocabulary. The final diary entry read, “I feel I have improved a lot.” Wakao reflects: “Thanks to AI, it wasn’t ‘30 days of writing and forgetting,’ but ‘30 days of writing better sentences.’ That made a big difference.”

Katsumasa Kajikawa, 45, an executive of the GRAS Group, which provides Weblio Study, notes that AI’s text-generation ability has reached a level where it can be used for lesson planning and assignment creation. But he also cautions that students do not always interpret AI feedback correctly.

Nevertheless, Kajikawa highlights how students’ behaviors change once they become accustomed to AI. “What’s interesting is that after experiencing the comfort of AI, many students feel they want to speak for themselves.” AI translation enables communication in a foreign language, but students develop a desire to communicate directly with their own words. Human-to-human communication cannot be replaced by AI, and having something one genuinely wants to express becomes the driving force for learning.

AI now translates, edits, explains and even supports conversation. Yet the reason people continue to learn lies not in AI, but in the inner desire to “say something” themselves. In the age of AI, the purpose of learning a foreign language is, in fact, returning to the individual. The teacher’s role is shifting toward uncovering and supporting those personal “reasons.”

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Makoto Hattori

Makoto Hattori is a staff writer at the Yomiuri Research Institute.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Myanmar Will Continue Under Military Rule Even After Election, Ex-Ambassador Maruyama Says in Exclusive Interview

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

Expansion of New NISA: Devise Ways to Build up Household Assets

-

China Criticizes Sanae Takaichi, but China Itself Is to Blame for Worsening Relations with Japan

-

Withdrawal from International Organizations: U.S. Makes High-handed Move that Undermines Multilateral Cooperation

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time