Koichi Wajima poses in the Wajima Koichi Sports Gym in Suginami Ward, Tokyo.

9:00 JST, December 23, 2024

Wajima Koichi Sports Gym is located in Suginami Ward, Tokyo. Among the trainees who were dripping in sweat, there was a man in his 80s with a burning spirit.

Although his second son, Hirokazu, took over the position of chairman of the gym, Koichi Wajima still goes there at least once a week.

“My physical strength waned as I had predicted,” the former world boxing champion said enthusiastically with his thick arms extending forward. “It’s not only because of the damage from being punched. In those years, I abused my body 10 times harder than others did to better utilize my short arm reach.”

Wajima sometimes shows his comedian-like personality, as has been seen on TV programs.

“When I talk about ‘reach,’ many people tell me, ‘Hey, we’re not talking about mahjong,’” he said with a laugh. The pronunciation of “reach” is the same as the mahjong term ‘richi.’

Wajima was born in 1943 in Sakhalin, which at the time was called Karafuto by the Japanese. In his childhood, he grew up in Shibetsu, a city in northern Hokkaido.

It was a time when there were serious food shortages in Japan.

“I often took watermelons from farm fields, thinking I was doing a very foolish thing,” he said. “It was because I would have died unless I ate something.”

He was adopted by a relative’s family and lived in Setana, a town in Hokkaido facing the Sea of Japan, from his senior years of elementary school to middle school.

At night, he worked on a fishing boat to catch squid and suffered from seasickness all the time. When the sea was too stormy and fishing was impossible, he cut down trees in the mountains and carried the lumber.

“I’m bowlegged because I lugged heavy items the same way as adults did since when I was a small child,” Wajima said.

He never got enough sleep. He often fell asleep during school, and teachers would scold him.

“Because I experienced such things, I have never been shocked at whatever happened to me. I told myself that I would never be defeated. This helped me in boxing,” he recalled.

He moved to Tokyo when he was 17. While working for a construction company, he came across Misako Gym, which fostered boxers. The gym was located near the construction company’s dormitory.

“I wanted to demonstrate, in some form, my feeling that I didn’t want to be defeated by anything,” he said.

Although Wajima applied to join the gym with the intent to show his fighting spirit, gym officials did not take him seriously at all.

“When I told them, ‘I’ll be 25 in three months,’ I was told: ‘Oh, is that so? Go somewhere else,’” he said.

Masahiko “Fighting” Harada, also a world boxing champion and who was born in the same year as Wajima, retired at the age of 26. As was seen in his case, a professional boxer’s career in those days was shorter than today.

Many trainees began boxing in their teens, so Wajima’s attempt was regarded as reckless in that context.

The “old man” debuted as a professional boxer at 25 in 1968. After that, Wajima’s unexpected run continued.

After debuting, he won by knockout in seven matches in a row. Then he won the title of rookie of the year and became the champion in Japan’s super welter-weight division.

In 1971, Wajima’s fourth year as a professional boxer, he got the opportunity to fight Carmelo Bossi of Italy, who held the world championship of the division.

Facing a boxer with high-level skills, Wajima, who had an irregular style because of his short arm reach, fought by fully using his brain. It was in this match when Wajima used a surprise attack technique, dubbed a “frog jump,” in which he ducked down, jumped up and struck blows. The technique became famous as his weapon.

“I thought things would go well if I could irritate the opponent. He got angry and struck me,” Wajima said.

Wajima psychologically confused his opponent and lured him into a volley of trading punches, which he was confident would work in his favor. As a result, Wajima won by decision.

Wajima snatched the championship belt in the division, which was then called “junior middle.” At the time, Wajima became the world champion in the division of the heaviest-weight boxers in Japan. A newspaper headline praised the victory as “the first Japanese champion in a heavyweight division.”

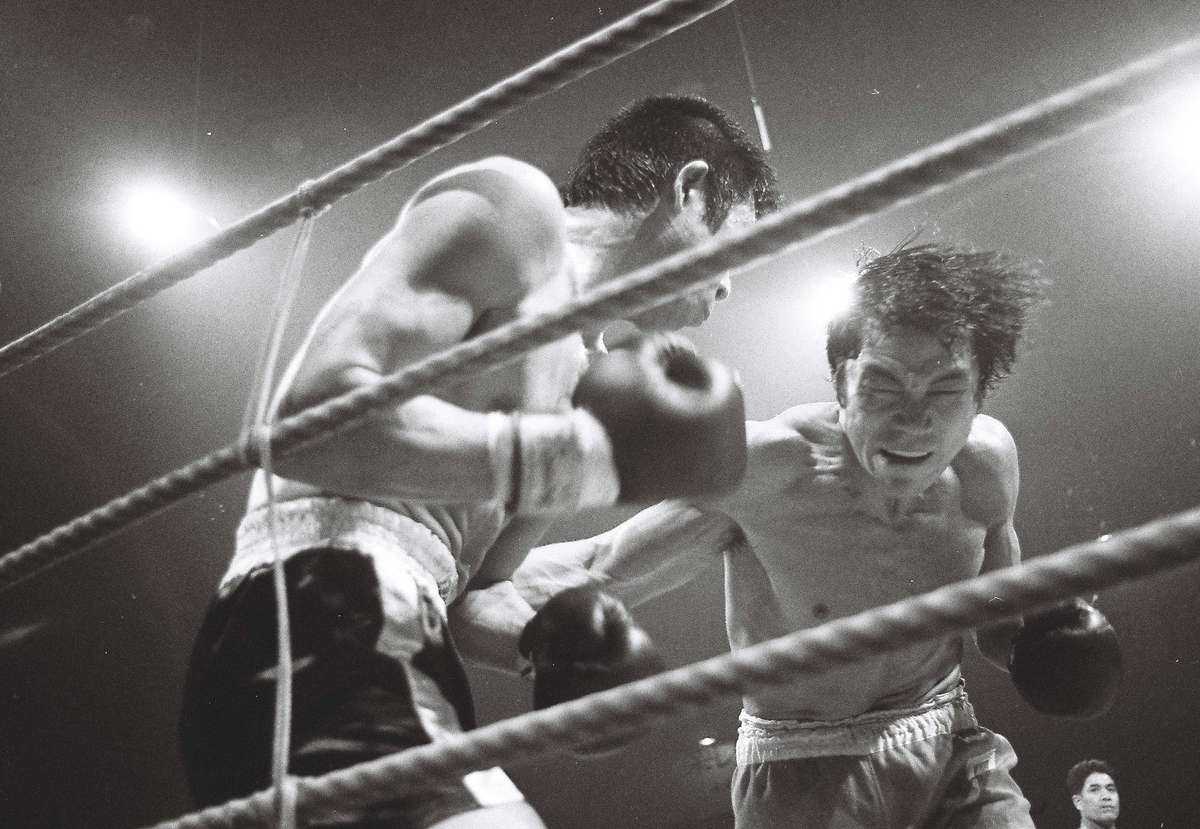

Wajima, right, defended his title in Osaka in 1973.

In 1974, in his seventh defense match, Wajima was defeated by knockout by Oscar Albarado of the United States. But in the following year, Wajima took back the championship belt from him.

In the same year, Wajima lost the championship belt again as Yuh Je Doo of South Korea defeated him by knocking him out. But Wajima did not give up on his career as a professional boxer.

“All the people around me thought I would retire, but I believed I would be able to win,” Wajima said. “Everybody lowers their guard in their mind the second time. I aimed to hit the point.”

In 1976, when Wajima met Yuh and his staff just before the second match, he wore a face mask while pretending to have caught a cold. Yuh was confident, and even showed a smile during the match, Wajima recalled.

From the first round, Wajima proactively attacked and controlled the pace of the match. In the 15th and final round, his right punch struck and knocked down the opponent.

Wajima took back the championship belt twice. Also, at 32, this time he was the oldest among Japanese boxers.

The dramatic victory that overturned common sense in the boxing world excited people all over Japan. The average household viewer rate of the TV broadcast, which was measured by Video Research Ltd. in the Kanto region, was recorded at 42.5%.

“These short arm reaches of mine could not hit opponents unless I betrayed their predictions again and again and again. To win, it was essential for me to outwit my opponents,” Wajima said.

Later, Wajima fought in two matches, lost both, and retired in 1977. The man of “burning spirit” left the ring after feeling burned out.

Wajima has a message for today’s boxers: “With training, you need to have guts, and with fighting in a match, you need to be brave. Those who lack courage in real matches cannot ascend to higher positions.”

By converting difficult experiences in childhood into a spirit of resistance, the man who had continued fighting with guts and braveness in the Showa era (1926-89) marched on. His remark has a strong, convincing power.

Unprecedented in many aspects

Japanese boxers in history have been strong in lightweight divisions, but they have still not reached world-class achievements in middleweight and heavyweight divisions.

Considering this, it deserves special mention that Wajima defended his championship belt six times in the super welter-weight division.

It is also noteworthy that he overcame the weak point of his short arm reach. Wajima is about 170 centimeters tall and the total reach of both his arms is about the same. Because there are boxers who are 180 centimeters tall or taller in the division, it is understandable that Wajima had to punch skillfully and sway the attacks from his opponents.

Makoto Maeda, 76, a former editor-in-chief of Boxing Magazine, pointed out: “Wajima’s strongest point was his cleverness. He fought in a tricky way while reading the minds of his opponents.”

After retiring as a boxer, he began running a dumpling shop, surprising those around him.

“With much money and time, a person only wants to do something enjoyable. By whiling away my time with that job, I won’t go in the wrong direction,” Wajima said.

By exercising his cleverness, Wajima started the second round of his life.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan