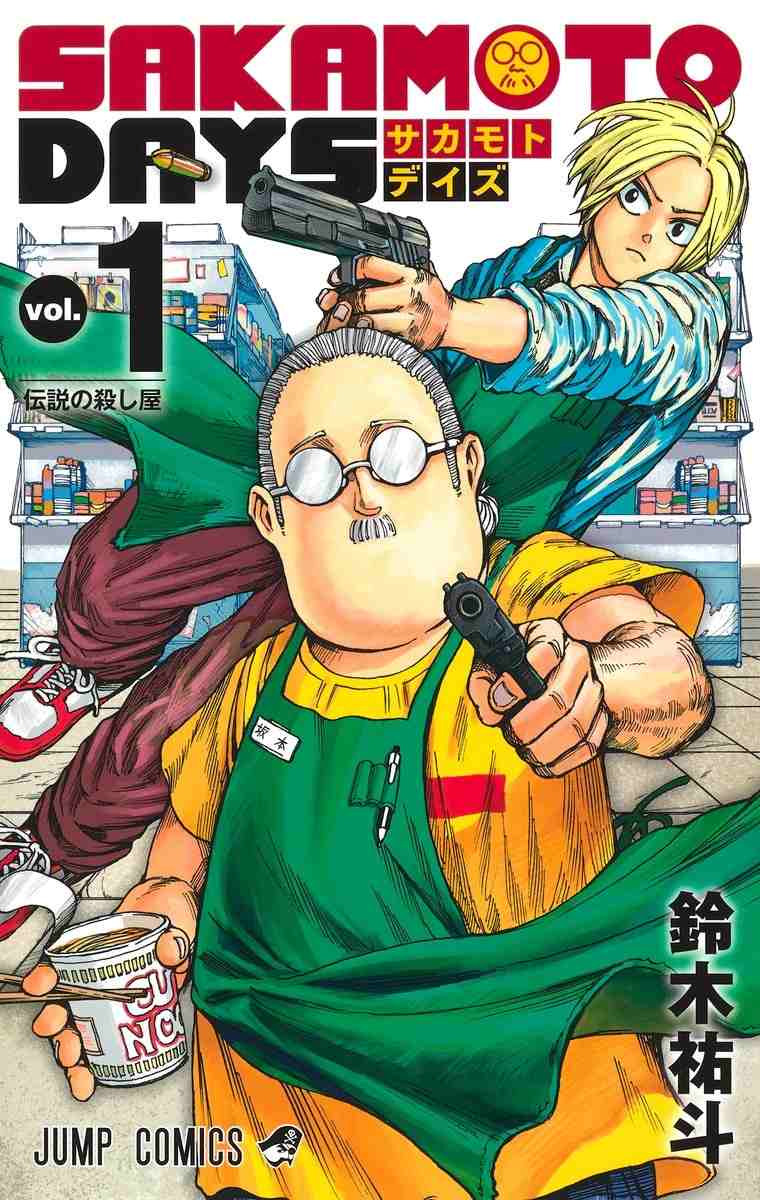

‘Sakamoto Days’ A Thrilling and Visually Innovative Chronicle of the Life of A Retired Assassin

Sakamoto Days

by Yuto Suzuki (Shueisha)

12:00 JST, December 20, 2024

Some manga series make us realize decades later that they changed the “grammar” of manga, even though they were not considered major hits during their magazine serialization. One example is “Jojo no Kimyona Boken” (“Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure”) by Hirohiko Araki, the serialization of which began in 1986. Another example is “Grappler Baki” by Keisuke Itagaki, with its serialization beginning in 1991. Both works are still very popular, and their magazine serializations continue to this day. But more importantly, they are noted for their artwork’s high level of “contagiousness.” In other words, their artistic expressions were so new that other mangaka wanted to imitate them.

Looking from this perspective, I sense a similar kind of novelty in “Sakamoto Days,” which is currently being serialized in the Weekly Shonen Jump manga magazine. Although it was seemingly eclipsed by the popularity of two big titles, “Jujutsu Kaisen” and “My Hero Academia,” both of which recently concluded, I suspect the real behind-the-scenes boss of Shonen Jump may in fact be “Sakamoto Days.”

The story is about Taro Sakamoto, once the mightiest of an assassin organization in Japan. Married and retired, he is now the owner of a convenience store. Since no one is allowed to leave the organization, a young hitman named Shin is sent to kill Sakamoto. Shin is a psychic who can read other people’s minds, but, for some reason, he is no match for Sakamoto, who is now flabby and overweight. Shin becomes fascinated with Sakamoto, who hires him as a clerk at the convenience store. But a ¥1 billion bounty is placed on Sakamoto’s head, and expert assassins come one after another to claim it.

Sakamoto has pledged to his wife that he will never kill again, so he basically goes around unarmed. Instead of using a weapon, he fights with whatever he can find around him. In the first episode, Sakamoto impressively fights Shin, who is armed with a gun, using only merchandise from the convenience store’s shelves. In following episodes, Sakamoto continues to fight in unexpected and complex situations that other mangaka would definitely shy away from drawing, such as on a roller coaster at an amusement park, inside a subway car, high up on the steel frame of Tokyo Tower, and in a department store (all of which are extremely difficult to draw!). Surprising and elaborate action sequences comparable even to a Hollywood blockbuster unfold in these scenes.

The assassins appearing in “Sakamoto Days” are all vicious and crazy. The latest volume, the 19th, features Takamura, a seemingly senile old man who is actually a swordsman with the ability to slice a building in two in one fell swoop. The drawings in a series of sword fights between Takamura and Sakamoto, which lead to the defeat of Takamura, are simply great. It is incredible how mangaka Yuto Suzuki came up with the idea of Takamura using his Japanese sword, which has a dull blade, to catch a bullet aimed at him and then letting the bullet rub against the blade to sharpen it.

Seeing scenes like this every week is likely to make other mangaka contributing to Shonen Jump feel uneasy. I am quite convinced that “Sakamoto Days” is the driving force behind a recent improvement in the standard of artwork in Shonen Jump as a whole. The manga has also scored a long-absent smash hit in portraying surprise that cannot be expressed in words by using the onomatopoeia “… chi!” This is on par with the success of the famous “… tsts!” invented by Itagaki of the “Baki” series, which is still popular today.

When Shonen Jump began carrying “Sakamoto Days” in 2020, it was more like a comedy. However, too many characters have died in recent installments, which may be preventing the work from being nominated for popularity rankings at year-end manga awards and other prizes. Yet the novelty of Suzuki’s artistic expression is by all means real. This viral “contagious” effect will surely have a long-lasting impact on future generations of mangaka.

Ishida is a Yomiuri Shimbun staff writer whose areas of expertise include manga and anime.

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan