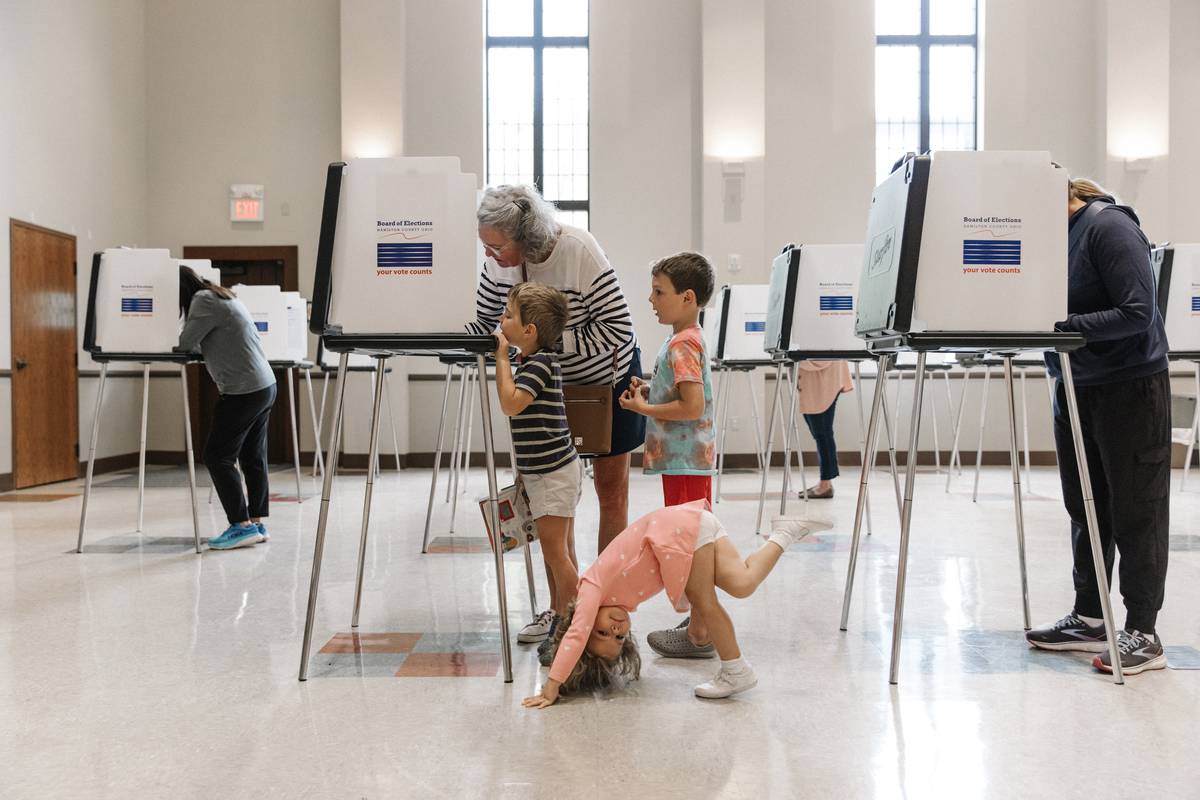

Sandy Spoerl, 66, votes for Donald Trump in Cincinnati on Tuesday as her grandkids Maddy, Sammy and Benny accompany her.

13:49 JST, November 6, 2024

Two very different Americas went to the polls Tuesday, and only one will emerge victorious. The 47th president, whether Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, will then face the daunting challenge of trying to govern a nation whose citizens see the world in dramatically diverging ways.

At their best, elections help resolve disagreements about how to deal with the nation’s biggest problems. They are carried out peacefully and harmoniously, with competing coalitions respecting what the other side brings to the debate. When they are over, the losers accept the outcome.

But these are anything but normal times. For the third time in as many elections, Americans were put through the wringer in a campaign that exposed the rawest edges of a changing society. The general election that pitted Harris, the Democratic vice president, against Trump, the Republican former president, was in many ways an echo of both the 2016 and 2020 elections – only the stakes were even greater, given the aftermaths of those previous campaigns.

Perhaps as never before, people were on edge – filled with anxiety and fear, hopeful but nervous – as they awaited results. Tens of millions voted before Election Day arrived, eager to register their preferences early. By the calculations of the University of Florida Election Lab, under the direction of Michael McDonald, 85.9 million people cast early ballots, with 46.7 million voting in person and 39.3 million sending in mail-in ballots. That represented more than half of the total number of votes cast in the 2020 election, which occurred early during the covid pandemic.

Elections, too, are about fundamentals, about the voters’ perceptions of the state of the country and the hopes and dreams they bring as they assess the candidates. But this election, even more than the last two, was fundamentally about the question of whether Trump would be restored to power despite his criminal conviction and two impeachments, or defeated for the second and perhaps final time.

On that question, the country was deeply divided, along lines of gender, race and education. They were divided also over questions of culture and values – and on which issues were most important. For those in the Trump camp, that meant immigration and inflation. For the Harris constituency, abortion rights rose above the others. For both sides, the question of democracy loomed large, though perceptions of what threatens democratic norms were starkly different.

This year’s winner will make history. If she wins, Harris, who is Black and South Asian, would be the first woman to be elected president. Eight years ago, Hillary Clinton sought to break that same barrier, only to lose to Trump in an upset that changed the country as few imagined it could. If he wins this year, Trump will become the first president since Grover Cleveland in 1888 to have been defeated after one term, only to win the subsequent election four years later.

No candidate carried more baggage into an election than the former president. He was twice impeached and twice acquitted while in office, convicted on 34 counts of falsifying business records in a New York case, held liable for sexual assault and indicted by the Justice Department for attempting to subvert the 2020 election results, including his role in sparking the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, a case that is still pending.

That record was enough to persuade roughly half of the country that he should never be entrusted with the powers of the presidency again. Harris played on those fears, which were more intensely felt among women than men, to fuel a candidacy that wasn’t even imagined at the beginning of summer before she replaced President Joe Biden atop the Democratic ticket.

And yet, on the morning of Election Day, the polls showed Trump and Harris battling almost evenly across the seven states that would decide who enters the Oval Office on the afternoon of Jan. 20. That was because, as much as Trump was a magnet for opposition among those who regarded him as unfit to be president, he was an equally powerful magnet for a similarly sized army of people who believed he spoke for them in ways no traditional presidential nominee has.

The contest was also close because Harris was trying to overcome burdens of her own, principally negative public perceptions of the state of the country and of Biden’s performance in office. A sizable majority of Americans said the country was off track, heading in the wrong direction. A majority said they disapproved of the way Biden has handled his responsibilities. In normal times, those factors alone would be enough to threaten, if not sink, the candidate of the incumbent party.

Harris entered the race July 21, the same day Biden announced he was standing down under pressure from Democratic leaders following his disastrous performance in his debate with Trump on June 27 in Atlanta. Harris was not truly battle tested for the road ahead when she leaped into the race. Her 2020 campaign ended before the first votes were cast. She became the 2024 Democratic nominee having faced no competition.

From a standing start, her campaign ballooned into a billion-dollar enterprise as the contest went through a transformation not seen before. In many ways, she ran a textbook campaign, but she was handicapped by the fact that many voters did not feel they really knew her and therefore were wary about entrusting the presidency to her, even if they had reservations about Trump.

The final days of the campaign were a study of contrasts. Trump was dark, foreboding, rambling and threatening. The tone was set at one of his final rallies, a mega event held in New York’s Madison Square Garden. Ahead of his speech, the event was a festival of racism and misogyny by campaign-approved speakers. One of them, comedian Tony Hinchcliffe, described Puerto Rico as “a floating island of garbage,” language that quickly went viral. Trump’s rallies were exercises in personal grievance. Only on his last full day of campaigning was Trump even remotely disciplined and on message – and yet even then, at his last of four rallies, just past midnight in Grand Rapids, Michigan, out of nowhere he attacked former House speaker Nancy Pelosi in crude, sexist terms.

Harris struck a different tone in her last week on the trail. She had been hammering Trump, saying she agreed with the characterization of some of his former advisers that he was a “fascist.” She returned to the issue of democracy that had been central to Biden’s message, one that she had pushed to the side during the period of the campaign described as “the politics of joy.”

But in the final week, beginning with a huge rally on the Ellipse outside the White House, the same spot where Trump had fired up supporters on the day of the Capitol attack, she shifted to more positive and optimistic themes. She stressed that she would be a president for all Americans, a president who would enter the Oval Office with “a to-do list” rather than “an enemies list,” a leader who would seek the ideas and advice of Republicans.

She also shifted in her assessment of the state of the campaign. Having said from the beginning that she was an underdog, she exuded confidence, claiming in the final hours that her campaign had the necessary momentum to carry her across the electoral college finish line. “We will win,” she said at her final rallies Monday evening. The final tallies will tell whether that was bravado or based on something her campaign had seen in their models.

Harris spent the last full day of campaigning in Pennsylvania, holding five events across the state. Her focus underscored the overriding importance of the commonwealth to her campaign and to Trump’s. Its 19 electoral votes were the biggest prize of all the battleground states, and both campaigns considered it vital to their hopes of winning the presidency.

The year started with six battlegrounds: Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin in the north, Georgia, Arizona and Nevada in the South and Southwest. As the year progressed, North Carolina, a state Barack Obama won in 2008 but that no Democrat had won since, was added to the mix as polls and the climate there showed that state to be competitive.

As the votes were being counted Tuesday night, Harris and her team saw the northern route – the so-called blue wall – as their clearest path to victory. Success in those three, plus a single electoral vote from Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, will make her president, though with the bare minimum of 270 electoral votes.

But a Trump victory in Pennsylvania would scramble the board. That and victories in Georgia and North Carolina, both with 16 electoral votes, plus a single vote from Maine’s 2nd Congressional District, would put the former president at exactly 270 and with a ticket back to the White House.

In the final days, the battleground states were awash with rallies by Harris, Trump, Democratic vice-presidential nominee Tim Walz of Minnesota and Republican vice-presidential nominee JD Vance of Ohio. Former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton as well as Michelle Obama stumped for Harris. Her final rallies included some of the biggest names in music and entertainment – Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Bruce Springsteen, Katy Perry and Oprah Winfrey. Trump’s rallies featured surrogates as well, but the focus was always Trump, symbolic of the singularity of his candidacy.

Battleground states were also swarming with paid staffers, volunteers and nervous supporters. They knocked on doors, wrote letters and postcards, made phone calls and often commiserated among themselves about the potential outcome. The Harris campaign assembled a massive get-out-the-vote operation, augmented by independent expenditure activity that included a sizable effort to mobilize college campuses. Trump decided to outsource this vital element of presidential campaigns to billionaire Elon Musk and conservative activist Charlie Kirk, a risky decision in the eyes of traditional strategists.

As polling places closed across the country and the networks and news organizations began to make their early projections, one overriding question was whether this election would sustain and extend the Trump years or prove to be a circuit breaker, a jolt to the system that might set the country on a quieter path. That did not happen four years ago, and few were betting on the answer as they awaited the declaration of a winner.

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

American Playwright Jeremy O. Harris Arrested in Japan on Alleged Drug Smuggling

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average as JGB Yields, Yen Rise on Rate-Hike Bets

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Licks Wounds after Selloff Sparked by BOJ Hike Bets (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Buoyed by Stable Yen; SoftBank’s Slide Caps Gains (UPDATE 1)

-

Japanese Bond Yields Zoom, Stocks Slide as Rate Hike Looms

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant; Inspects New Emergency Safety System

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by Deterioration of Japan-China Relations

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Security in Interview Ahead of Forum

-

Tokyo Economic Security Forum to Hold Inaugural Meeting Amid Tense Global Environment

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi’s Power Plans