Social Media and Elections: Lessons from Hyogo / Echo Chambers, Confirmation Bias Led to Threats Against Hyogo Politicians

A placard criticizing Motohiko Saito is seen behind him as he walks through a shopping street surrounded by supporters, during his election campaign in Chuo Ward, Kobe, on Nov. 10.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

6:00 JST, November 28, 2024

This is the second installment in a series examining how social media is impacting elections.

***

Kenichi Okutani, a Hyogo prefectural assembly member, received malicious phone calls at his home saying such things as “resign,” “liar” and “come outside,” during the recent Hyogo gubernatorial election campaign.

Okutani is the chairman of the Hyogo prefectural assembly’s so-called Article 100 committee, which is conducting probes into reelected Hyogo Gov. Motohiko Saito, 47, over allegations of power abuse and other problematic acts.

After Saito lost his position as governor prior to the election, slanderous posts about Okutani were spread on social media, while posts supporting Saito proliferated.

Takashi Tachibana, 57, leader of the political group NHK Party, also ran in the election. During the campaign, he delivered a street speech in front of Okutani’s home. He urged Okutani to “come out,” and livestreamed himself pressing the doorbell.

Okutani and his mother had evacuated from the house, but Tachibana went on to ask social media users on X, formerly Twitter, to provide information about any sightings of Okutani. Some posts in response said such things as, “He seems to be hiding in the Arima Onsen hot spring resort.”

Even after the election, strangers have kept standing in front of Okutani’s home and ringing the doorbell. He has consulted with police.

Okutani said with an exhausted expression on his face: “Posts about me on social media are all full of misinformation. This is the first time for me to fear this much for my physical safety.”

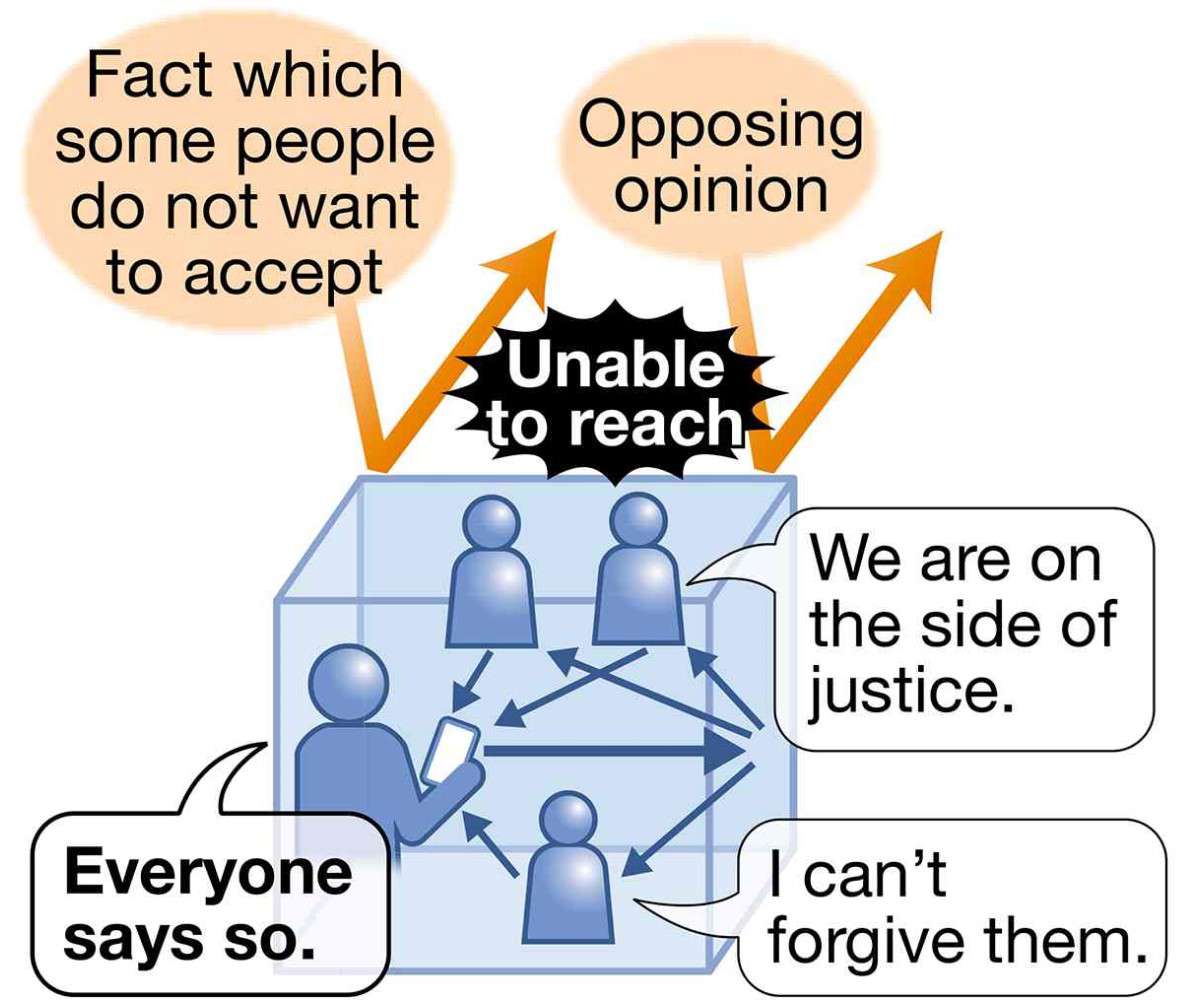

Echo chamber effect

How echo chamber effect works on social media

On social media, a phenomenon called the “echo chamber effect” tends to occur, as users’ ways of thinking become distorted as they are more likely to become connected only with other users who hold similar opinions.

Fujio Toriumi, a professor at the University of Tokyo and an expert in computational social science, said that only about 10% of accounts on X reposted posts both in support and in opposition of Saito during the election campaign period from Oct. 31 to Nov. 16.

He said that X users who supported Saito tended to repost only those posts made by supporters of the governor and opponents tended to only have contact with others who were critical of him, indicating that the two groups were cut off from each other.

It is possible that such echo chambers led to increasingly radical language being used among the two groups.

Okutani was not the only one targeted by such online abuse.

Kazumi Inamura, 52, who finished second in the gubernatorial election, was the subject of a campaign of disinformation on social media. There were posts that claimed she was trying to promote foreigners’ rights to take part in Japanese politics, even though she had never mentioned such a stance.

Her election office received phone calls in protest from people who wrongly believed the posts.

Yoshiaki Hashimoto, a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and an expert on information social psychology, said about the protesting phone calls, “It was probably a result of confirmation bias.”

Confirmation bias refers to the psychological tendency of people to only collect information that matches their own opinions. “It is possible that the protesters strongly believed that they were right and the sense of justice they held encouraged them to take such radical action. Even if others call for cool-headed discussions, they see them as enemies and never accept them,” he said.

An example of such an incident taken to an extreme was the attack on the U.S. Capitol Building in the wake of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Donald Trump refused to accept his loss in the election and called on people to participate in protest rallies or take other actions. As a result, a group of Trump supporters formed a mob and temporarily occupied the U.S. congressional building.

In Brazil in 2022, about 4,000 people, mainly supporters of a defeated presidential candidate, intruded into the National Congress and other public places based on information received through social media. They committed destructive acts.

Budding violence

In the recent Hyogo gubernatorial election, there was evidence of budding violence caused by divisions among the public.

At the venues of Saito’s speeches, jeers were heard alongside voices of support.

On Nov. 15, during the final phase of the election campaign, thousands of people gathered to hear Saito’s speech in front of JR Himeji Station. In response to opponents of Saito raising placards, some members of the audience repeatedly shouted, “Go home.” At one point, police officers entered the space between them.

A 42-year-old man from Nagata Ward, Kobe, held a paper sheet reading, “Shame on you, Saito.”

“Saito’s supporters are conspiracy theorists who blindly believe information on social media,” the man said.

The man said he got acquainted with fellow anti-Saito activists via social media.

Tatsuhiko Yamamoto, a professor at Keio University and an expert on constitutional studies, said, “If divisions accelerate on social media, [Japanese society] may fall into chaotic situations like those seen in the United States and Brazil, in which people tried to overturn election results with violence.”

“We need to have discussions as soon as possible about how we can build a system in which people can easily access objective and useful information, rather than extreme opinions,” he added.

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Director Naomi Kawase's New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Ja...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japan’s Mari Fukada Wins Gold in Women’s Sno...

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Rises on Tech Rally and Takaichi's S...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japan’s Taiga Hasegawa Wins Silver in Men’s ...

-

Mark Zuckerberg Quizzed on Kids' Instagram Use in Social Media Tr...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Russian Flag and Anthem Set to Return at Nex...

-

Takaichi Expected to Express Desire for Constitutional Revision P...

-

CARTOON OF THE DAY (February 19)

Popular articles in the past week

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected 105th Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All C...

-

Japan's Govt to Submit Road Map for Growth Strategy in March, PM ...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Figure Skaters Riku Miura, Ryuichi Kihara Pa...

-

Tokyo’s New Record-Breaking Fountain Named ‘Tokyo Aqua Symphony’

-

CRA Leadership Election Will Center on Party Rebuilding; Lower Ho...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reco...

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many Peop...

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages C...

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Befor...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station