Tsukiji Outer Market; surviving and thriving / Tsukiji Preserves Outer Market Culture with New Rules; History of District from Great Kanto Quake to COVID-19

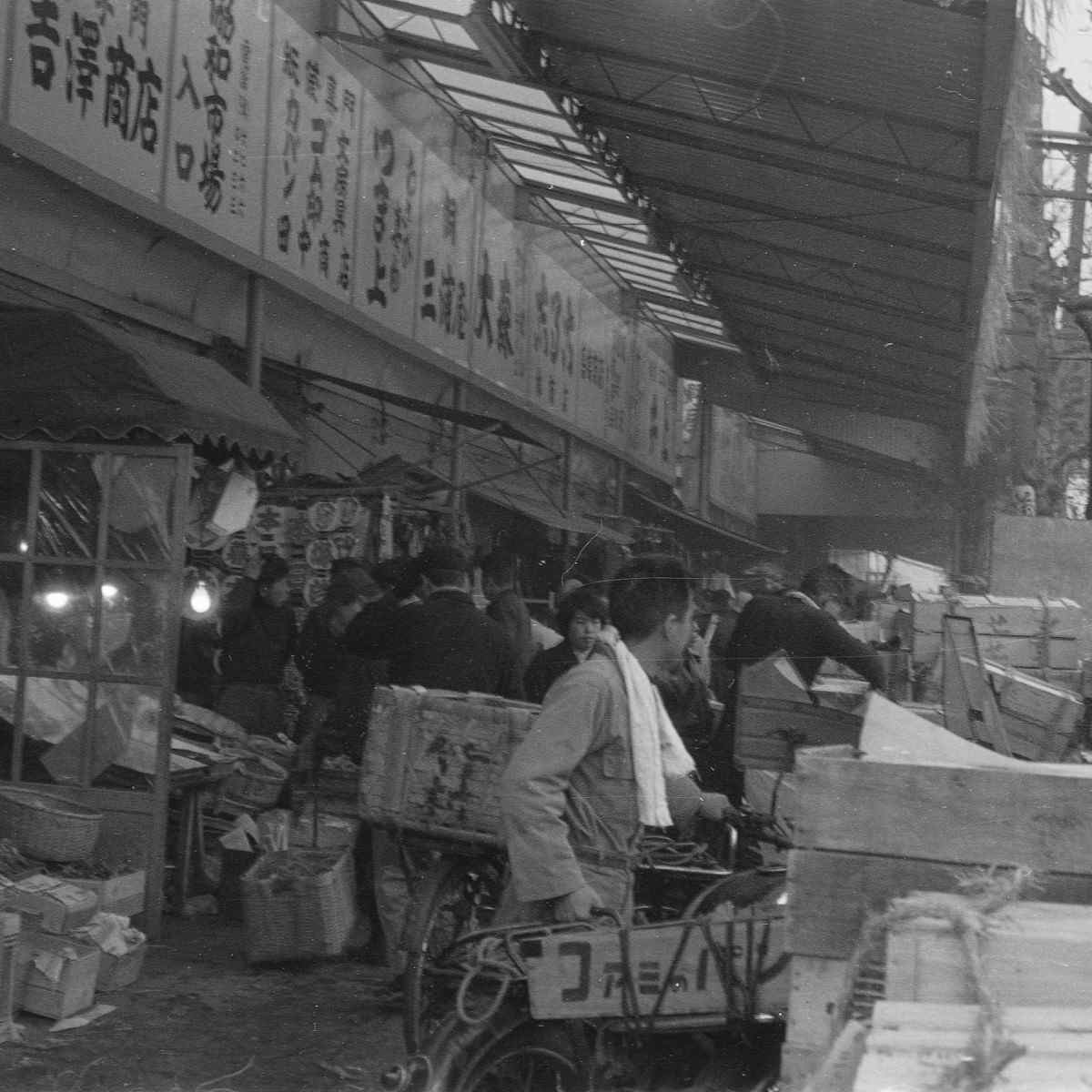

The Tsukiji Outer Market in 1956. The market was crowded with small stores just as it is today.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

15:41 JST, June 26, 2024

The Tsukiji Outer Market went through tough times following the relocation of the main market and then restrictions from the pandemic, but is thriving again as the original market area undergoes a massive redevelopment nearby. This is the second installment in a series on its attractions and charms.

***

“Tsukiji used to be a place where business and daily life were close-knit,” said Yoshiko Yamazaki who promotes the district of Tsukiji and its stores to tourists at “Plat Tsukiji,” a general information center at the Tsukiji Outer Market in Chuo Ward, Tokyo.

The history of Tsukiji dates back to the early Edo period (1603-1867). It was built at the mouth of the Sumida River as part of the Edo Bay (modern-day Tokyo Bay) reclamation project following the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657.

The reclamation work was said to be initially challenging due to rough seas. Legend has it, however, that people found a holy object floating on the waves, enshrined it and worshiped it as a deity. The waves then calmed down, leading to the successful completion of the work. This is the origin of Tsukiji Namiyoke Jinja shrine. Namiyoke literally translates to “protection from waves.”

As the district was suited for water transport and was home of samurai residences and tradesmen’s houses, wholesalers dealing with all kinds of goods arriving from all over the country lined the streets, causing the whole area flourish.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), a foreign settlement was created and hotels exclusively for foreigners were set up, reportedly filling the streets with the scent of civilization and enlightenment.

The creation of the outer market was triggered by the Great Kanto Earthquake in September 1923.

In the wake of the quake, Nihombashi fish market was destroyed by fire and was relocated to the Tsukiji district, where the Ministry of the Navy had a plot of land. There, a makeshift public market began operating. Vendors from the Nihombashi area, and those who were starting their businesses, gathered outside of the market, forming a prosperous shopping quarter.

While the wholesale shops at the makeshift fish market sold marine products to business operators such as restaurants and retailers, the stores in the outer market thrived by dealing in a wide range of dried and ready-prepared foods not available at the temporary market and they even sold cooking utensils.

When Tsukiji Market opened in 1935 to succeed the makeshift market, the streets had already become what they look like today, with numerous stores lined up, including grocery stores and shops selling tamago-yaki rolled omelets and katsuobushi dried bonito.

Uzumi Yoshida, vice mayor of Chuo Ward, who has been involved in the community development of the ward for more than half a century, said, “The Tsukiji and Nihombashi fish markets have both been essential to the narrative of Tsukiji district’s development.”

Post-war reconstruction

While the districts of Ginza and Kyobashi were razed by air raids during the Pacific War, the outer market, surrounded by a river and high streets, miraculously escaped the damage.

“As the stores were undamaged, the post-war reconstruction of the streets progressed quickly once goods started coming in from across the country,” recalled Takashi Suga of “Suga Shoten,” a ready-prepared food store established in 1948.

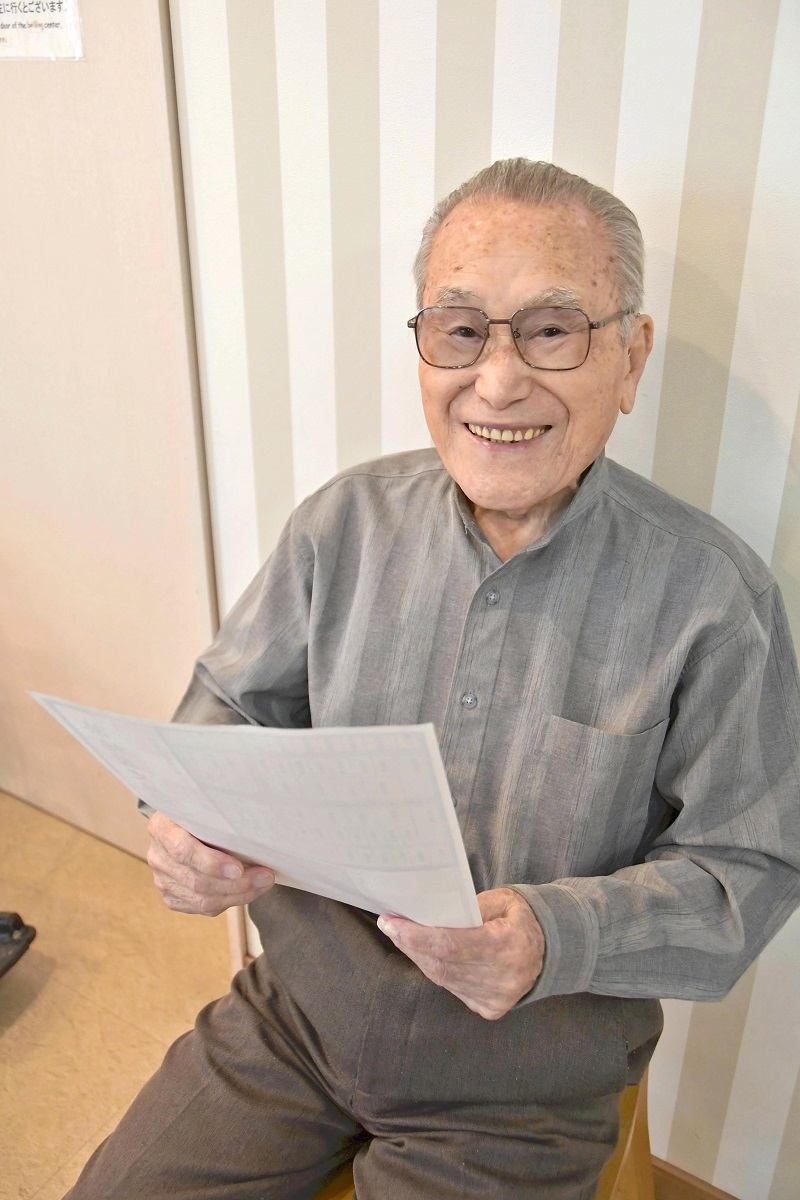

Takashi Suga, 98, speaks about Tsukiji.

Suga, who was born and raised in Tsukiji, started a kamaboko fish paste store after he was demobilized, together with a kamaboko vendor from Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture, by renting a corner of his property to the vendor.

It was in the days of a dire food shortage, where anything that could be eaten could be sold easily. Whenever the shop increased the variety of food on offer, such as shumai steamed pork dumplings, meatballs and stewed cubes of bonito, the number of customers also increased.

As soon as the store opened early in the morning it would be dizzyingly busy, with a succession of orders coming from one customer after another. By noon, however, trading for the day was over.

The upper floors of the stores were where the store owners and their families lived. The alleyways in front of the stores would be teeming with children playing menko, a children’s game where thick cards would be thrown down on the ground to turn over those of their opponents.

It was an era when, if a child was spotted being mischievous, adults would tell him or her off even if they were not their own.

The Tsukiji Shishi Matsuri festival at Tsukiji Namiyoke Jinja shrine is a major annual community event held in early summer.

Suga would play the flute at the festival, while his childhood friends would beat taiko drums, and they all carried a mikoshi portable shrine, deepening their bonds. Suga said, “The whole town was just like brothers and sisters back then.”

New development

The Tsukiji Outer Market, lined with small stores, is bustling with tourists in Chuo Ward, Tokyo, on May 11.

Through the period of rapid economic growth (from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s), the volume of marine products handled at Tsukiji Market meant it became one of the largest markets in the world, with the “Tsukiji brand” spreading even overseas.

Although Tsukiji Market was relocated to Toyosu in Koto Ward in October 2018, many stores in the outer market have remained in Tsukiji, and the outer market continues to attract crowds, particularly of foreign visitors to Japan.

In the past few years, however, as new vendors moved in from the outside to open stores on the former sites of stores that went out of business during the COVID-19 pandemic, problems have become apparent, such as the parasols of some stores overhanging their premises, hampering customers as they walk along, or customers littering as they eat while walking along the streets.

Considering such developments, a non-profit organization made up of stores in the outer market in April formulated the guidelines for business operators in the outer market to follow.

In order not to spoil the aesthetic of the outer market and its lines of small stores, the guidelines call for buildings either to be built anew or remodeled to be in harmony with their surroundings, such as by using the first floor of the building as the store.

To promote “good-natured business that is considerate of its surroundings,” the guidelines also ban the placement of billboards, signs and displays of merchandise on public roads. They also established voluntary rules, such as sweeping in front of the store every day.

These guidelines have reportedly proved effective already. For instance, one retailer removed a refrigerator that had been jutting out into a public road.

Yoshitsugu Kitada, the organization’s chairman, said, “Tsukiji has been able to continue its business chiefly by steadily making regular customers. Therefore, it is important to carry on and develop further the culture that ‘Tsukiji, a food town,’ has cultivated through generations for many years to come.”

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Surviv...

-

Massive Sewer Pipe Found Jutting Out of Highway in Osaka

-

Japan-U.S. Summit Likely to Focus on Middle East; Takaichi to Fac...

-

Hawaii Museum on Tsunami Including Japan's 2011 Disaster at Risk ...

-

15 Years since Great East Japan Earthquake: How Can Affected Area...

-

Japan Holds Memorial Events to Mark 15th Anniversary of 2011 Eart...

-

Japan Train Company to Increase Fares, Including in Tokyo Metropo...

-

Japan’s Mitsui O.S.K. Lines Container Ship Anchored in Persian Gu...

Popular articles in the past week

-

Ibaraki Pref.'s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

-

Nippon Life Insurance's U.S. Arm Sues OpenAI Over Legal Assistanc...

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Surviv...

-

Govt to Utilize ODA for Ensuring Economic Security; Securing Ener...

-

Massive Sewer Pipe Found Jutting Out of Highway in Osaka

-

Amid Strait of Hormuz Blockade, Shipping Companies Scramble to Ge...

-

Beckoning Cats Get Makeover to Fit Modern Lifestyles with Sleek D...

-

Japan Govt Survey Finds Just 10% of Workers Want Working Hours to...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanes...

-

South Korea Tightens Rules on Foreigners Buying Homes in Seoul Me...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Ibaraki Pref.’s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed