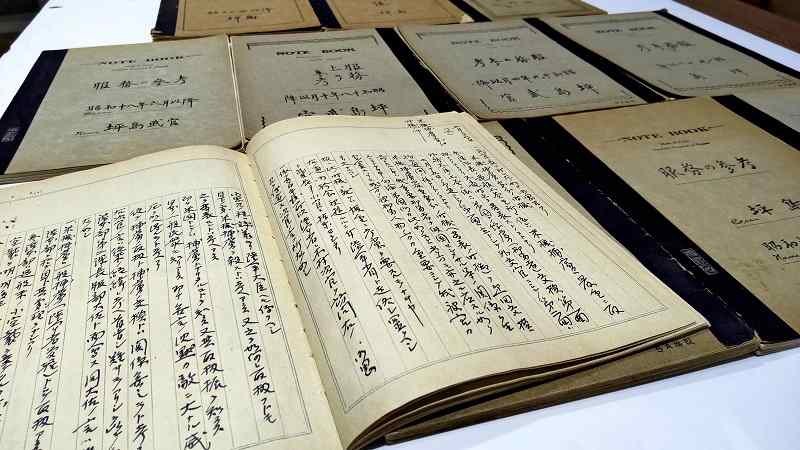

The diaries of Emperor Showa’s aide-de-camp Fumio Tsuboshima have been accessible at the National Diet Library’s Modern Japanese Political History Materials Room.

12:16 JST, May 28, 2022

Emperor Showa’s undisguised worries and concerns during World War II were preserved in the diaries of an aide-de-camp, which were publicly unveiled Friday at the National Diet Library’s Modern Japanese Political History Materials Room in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo.

The diaries of Fumio Tsuboshima (1893-1959), an aide-de-camp to Emperor Showa during the Pacific War, vividly describe the emperor’s worry about Japan’s post-war prospects, the tears he shed watching a newsreel about suicide attack units and his agony over the deteriorated war situation.

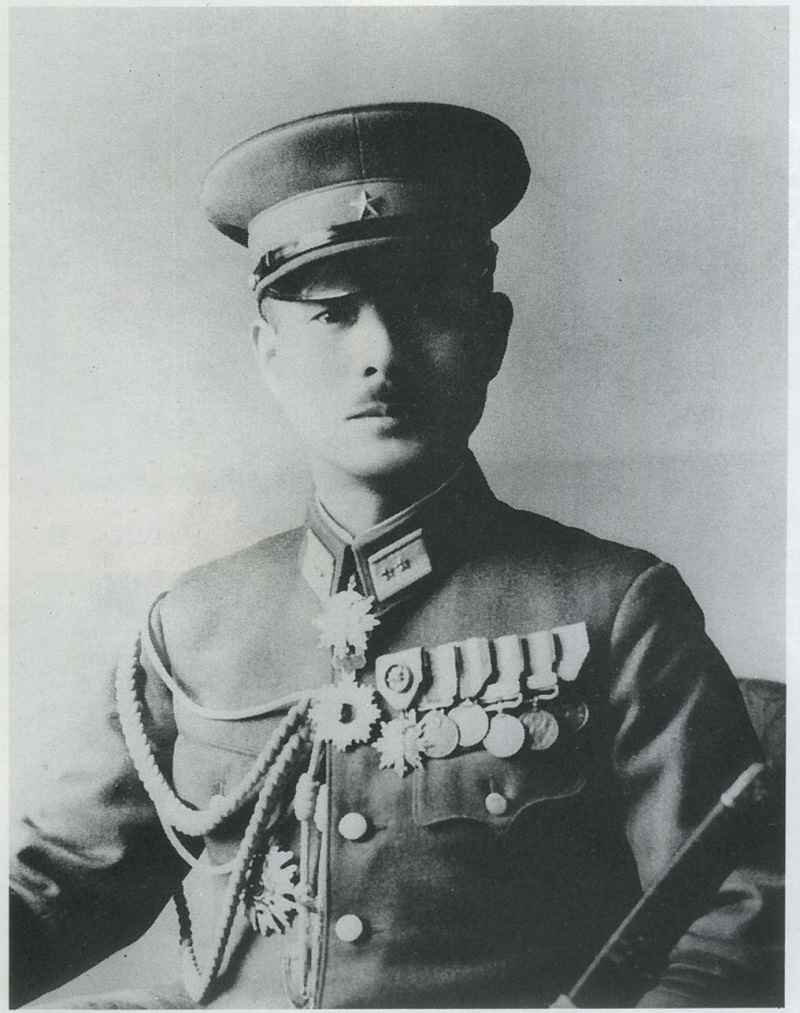

Fumio Tsuboshima

Experts see Tsuboshima’s diaries as a valuable document that expresses the emperor’s sense of desperation, as seen by an aide-de-camp who was close to the emperor.

Almost always at the emperor’s side, it was his job as an aide-de-camp, working under the chief aide-de-camp, to serve as a liaison between the emperor and the military, such as by reporting to him about military matters, transmitting his orders, and being dispatched as an Imperial representative when the army or navy conducted military exercises or military inspections. Tsuboshima was appointed to the post in September 1941 and served until March 1945.

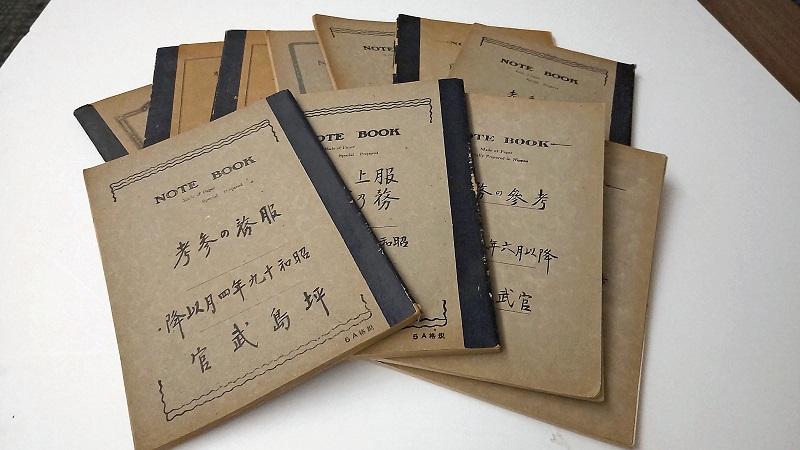

Tsuboshima’s war diaries comprise 11 notebooks in which he wrote about events from December 1941 to March 1946. The diaries were kept by his family for a long time after his death and were not even included in the source materials for the biography of Emperor Showa compiled by the Imperial Household Agency. In November last year, the family donated them to the library.

Back then, Tsuboshima was a major general — later promoted to lieutenant general — and worked with Shigeru Hasunuma, the chief aide-de-camp. He had access to much crucial war-related information.

According to his diaries, an entry for March 7, 1945, states that the emperor “wiped away tears” while watching a newsreel scene about a suicide attack unit writing down messages before going to the war front.

Ponder the end of war

Tsuboshima’s notebooks, with “Reference for service” written on their covers, are filled with Emperor Showa’s remarks worrying about the state of the war and the situation the soldiers were in.

In an entry dated Jan. 3, 1943, about fighting in the South Pacific including in New Guinea, the emperor warns soldiers not to let down their guard by saying: “While you believe you’re fighting against a part of the enemy, its powerful force may advance or its new airfield may appear before you know it. So, you need to be careful.”

The cover of Tsuboshima’s diaries reads “Reference of service.”

There is also a description of Emperor Showa around that time muttering to himself while taking a bath.

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science researcher Naoki Iijima said, “The diaries have deeply interesting depictions of Emperor Showa that vividly show his agony when the war situation takes a bad turn.”

In an entry dated Feb. 3, 1943, Emperor Showa, who was concerned about the soldiers’ food supply, asked Tsuboshima, “How is food stored in tropical areas?”

The description shows the emperor paid attention not only to the war situation but also to the food for soldiers in the harsh conditions of the battlefield.

However, after February 1944, when the U.S. Army raided Truk Lagoon, which was then a major Japanese military base and is now part of Chuuk State in the Federated States of Micronesia, Emperor Showa began to speak less about the war situation.

According to an entry dated March 27, 1944, hearing the vice chief of staff’s report on the war situation, the emperor said: “It sounds like you are saying we can make it if we try hard. Of course, there is nothing wrong with trying hard. But if the nation is driven into a corner, it will be difficult to recover its power after the war,” implying that the tide of the war had started to turn against Japan and showing concern about the nation’s postwar condition.

In response to the emperor’s remarks, Tsuboshima wrote, “I am humbled by the Emperor’s worry over how to end this war.”

Fumitaka Kurosawa, a professor emeritus at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University who specializes in the modern history of Japan, said the Emperor “must have contemplated the end of the war while thinking of the deteriorating war situation in Japan, combined with the global situation.”

Meiji University Prof. Akira Yamada, who is familiar with military history and Emperor Showa, said he knew of no other diaries left by general-class officers in a position like aide-de-camp during the war.

“In addition to words spoken by the emperor during World War II, facts and figures were recorded in extreme detail, apparently to be ready for questions and inquiries from the emperor,” Yamada said. “In that sense, the diaries are valuable historical material for understanding the quality and quantity of information obtained by the emperor at that time.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza