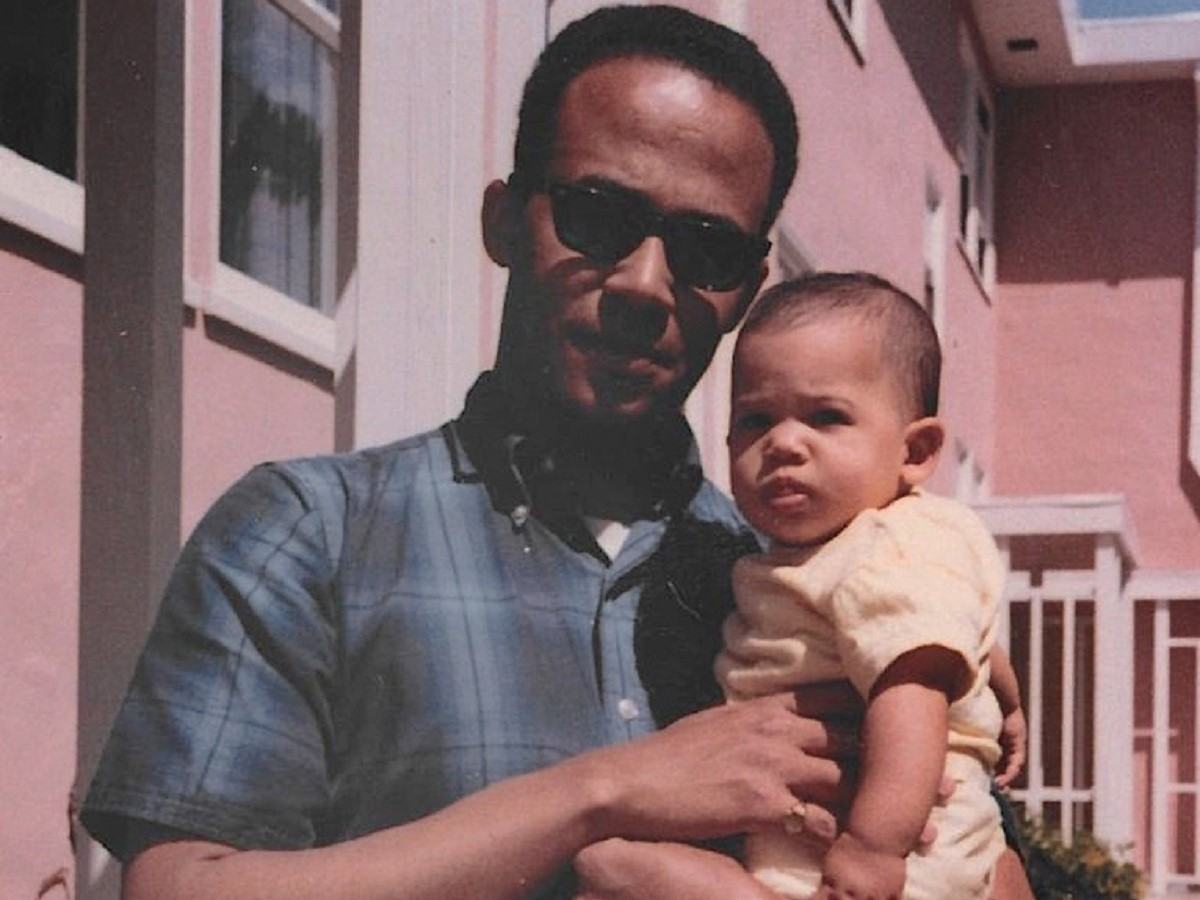

Donald Harris with Kamala in April 1965. At the time, he was on his way to a doctorate in economics at the University of California at Berkeley.

17:01 JST, August 14, 2024

The debates stretched late into the evening and sometimes well past midnight. At their offices in Jamaica’s capital city, after the nighttime cleaners had come and gone, Gladstone “Fluney” Hutchinson and his colleague Donald J. Harris would lock horns over technical questions related to the Caribbean nation’s economic development – how to diversify exports, options for tax reform, what might boost worker productivity.

Nearly every day for about eight months in 2012, the father of Kamala Harris – now the U.S. vice president and Democratic presidential nominee – worked with Hutchinson to craft what would become a 294-page document laying out an economic growth strategy for Jamaica, which at the time was suffering from sluggish growth and cripplingly large debt. The “growth inducement” document the longtime friends produced after hundreds of meetings with private-sector and civil-society leaders is viewed by some former Jamaican officials as playing a key role in righting the country’s economy in the decade since. Donald Harris later received the Order of Merit, Jamaica’s third-highest national honor.

“Donald Harris’s policy work was absolutely foundational to the Jamaican economy,” said Hutchinson, an economics professor at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania.

Since Kamala Harris’s rise to national prominence, her father has been labeled a left-wing economist who often focused on abstract debates primarily of interest to fellow academics. The 85-year-0ld former Stanford University professor did spend much of his career immersed in arcane disputes over topics whose practical implications can be hard to discern immediately. His 1978 book, for instance, is a 313-page dissection of centuries of competing concepts about the nature of capital accumulation and income distribution, suggesting a fascination with economic theory purely for its own sake. But his role in trying to solve the practical economic problems of Jamaica – the country of his birth and youth – reveals a less-examined side of his career.

And some former colleagues say that work provides insight into the economist’s potential influence on his daughter’s worldview. They hear echoes of Donald Harris in elements of the vice president’s speeches – from her commitment to minority-owned businesses to her support for the Biden administration’s industrial policy initiatives.

“Part of the thing was Don Harris never left us – he was always involved, not just with Jamaica but with the Caribbean islands, even when he was at Stanford,” said Renée Anne Shirley, a Jamaican financial consultant who was a senior adviser to the island’s first female prime minister in the mid-2000s. “He understood being Jamaican and being Caribbean and being from an underdeveloped part of the world – that’s what he stood for, and I think is a formative part of who Kamala is as well.”

Several times over at least three decades, Harris advised Jamaica’s government on how to develop the nation’s economy. Coming from an academic steeped in Marxist theory, Harris’s recommendations – including privatization of airports, tax reductions for businesses, and a corporate land registry – can appear strikingly nonideological.

Jamaica is now widely recognized as a fragile economic success story. It has sustained significant growth amid surprisingly large reductions in its debt due to an unusual agreement with the International Monetary Fund, which some allies say Harris helped craft through the 2012 growth strategy.

“He was an invaluable resource whose opinions needed to be sought,” P.J. Patterson, Jamaica’s prime minister from 1992 to 2006, said in an interview. “To a very large extent, the economic improvements we are witnessing today were founded on the principles and the priorities established in his industrial policy, which have born expected fruit.”

Donald Harris and Shyamala Gopalan, the vice president’s mother, separated when Kamala and her sister, Maya, were young. Kamala Harris has said previously that she was raised by her mother, who died in 2009.

The extent of her current relationship with her father is unclear. After Kamala Harris joked about her Jamaican heritage during the 2020 Democratic primary race while admitting to having used marijuana, Donald Harris criticized her fiercely in a since-deleted post on a Jamaican website, accusing his daughter of perpetuating stereotypes. (Despite former president Donald Trump’s recent attacks on her heritage, Kamala Harris has embraced her identity as a Black American for decades.)

“My dear departed grandmothers … as well as my deceased parents must be turning in their grave right now to see their family’s name, reputation and proud Jamaican identity being connected, in any way, jokingly or not with the fraudulent stereotype of a pot-smoking joy seeker and in the pursuit of identity politics,” Donald Harris wrote at the time.

Neither the Harris campaign nor Donald Harris returned requests for comment.

Donald Harris’s comment reflected his loyalty to his native country. Born in Brown’s Town, Jamaica, in 1938, he would go on to study at University College of the West Indies and then the University of London, before eventually receiving his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in 1966. He later became the first Black person to be granted tenure in Stanford’s economic department, following a 1960s push by student groups for more racial and intellectual diversity in elite departments, said Nathan Tankus, research director of the Modern Money Network, who has studied Harris’s career and writings.

“It was that specific moment when that pressure was still live, when the impetus to transform the economics profession was still live,” Tankus said. “And he would be very focused on development, in a very practical sense.”

When Kamala and Maya were little girls, their father took them to Brown’s Town. In a 2020 essay titled “Reflections of a Jamaican Father,” Donald Harris said the girls were rewarded with “brawta” – a Jamaican word that roughly translates to “bonuses” – in the form of mangoes, naseberries (which have a nutty taste) and guinep (a small green fruit similar to a lychee).

Donald Harris, who dedicated his 1978 book to his daughters, later said these trips had a serious purpose.

“When they were more mature to understand, I would also try to explain to them the contradictions of economic and social life in a ‘poor’ country, like the striking juxtaposition of extreme poverty and extreme wealth, while working hard myself with the government of Jamaica to design a plan and appropriate policies to do something about those conditions,” Harris wrote.

By the late 1980s, Harris was giving Jamaican officials economic advice, according to Hutchinson. In the early 1990s, Patterson, then prime minister, made Harris a senior economic adviser and appointed him to lead the country’s national industrial policy board.

Many of Harris’s recommendations would be incorporated into “Vision 2030 Jamaica – National Development Plan,” the country’s 2009 long-term growth document, and a 2012 plan by the Planning Institute of Jamaica that Harris and Hutchinson directed and edited. Their efforts involved both officials in government ministries and a leadership team from the political opposition. (Damien King, executive director of the Caribbean Policy Research Institute, praised Harris for returning to help Jamaica but disputed that the 2012 plan played much of a role in the country’s economic rebound.)

Shirley, the financial consultant, said Harris was never one to discuss ideology but was “interested in ideas and figuring out what we needed to do.”

Harris, she said, wanted to see what sort of government investments could help move Jamaica’s agricultural producers up the “value chain,” meaning they would not just be exporting raw materials. He worried about the danger of overdependence on remittances from Jamaican migrants as a short-term solution to the country’s lack of foreign currency. Perhaps ironically given his own trajectory, Harris was also concerned that the economy was producing too many workers with postgraduate degrees – who would then relocate abroad, taking their talents with them – and argued that the government should achieve universal education for the broad population.

“Part of the thing was Don Harris never left us,” Shirley said. “He was always involved, not just with Jamaica but with the Caribbean islands, even when he was at Stanford.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza