Two Large Exhibitions of Ancient Haniwa Figures from Today’s Perspective; Five Haniwa Warriors Gathered for 1st Time

Several “Haniwa Warrior in Keiko Armor” pieces are on display at the Tokyo National Museum.

7:00 JST, December 2, 2024

Two large exhibitions in Tokyo are showcasing ancient haniwa clay figures, which are important archaeological research materials that have also attracted artists with their artistic value and, in recent years, have become popular as manga and TV characters.

The exhibitions display precious haniwa pieces, including national treasures, and artwork using haniwa motifs, giving visitors an opportunity to explore their significance in cultural history.

Haniwa were arranged on and around kofun ancient burial mounds of royalty or powerful families.

A huge cylindrical piece, more than 2 meters tall, and adorable animal dolls are among the roughly 130 items on display in the “Haniwa: Tomb Sculptures of Japan” special exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum in Taito Ward. They were made in the third through sixth centuries and have been excavated from various burial mounds from Tohoku to Kyushu.

The centerpiece is known as “Haniwa Warrior in Keiko Armor” (Keiko no Bujin), a statue of a warrior in iron armor. This is the first time that five pieces of this type, all believed to have been made in the same workshop, are displayed together. One of them, a designated national treasure, is owned by the museum, while the other four are on loan from other museums.

All five were made in the sixth century and excavated in Gunma Prefecture. When these ones were made, haniwa production had declined in the Kinki region in western Japan, which was the center of royal power at the time, but it continued in eastern Japan.

Masanori Kawano, senior researcher at the museum, said: “A unique haniwa culture developed in the Kanto region [in eastern Japan], beyond the reach of Kinki region haniwa influence.”

It is possible that this type of haniwa was modeled on a warrior who was skilled in horseback riding, as horse breeding flourished in the Kanto region at that time.

“Haniwa Dancing People” figures are on display at the Tokyo National Museum. In recent years, a new theory has claimed that these figures are leading horses, not dancing.

Another must-see is “Haniwa Dancing People” (Odoru Hitobito), two figures excavated from a burial mound in Saitama Prefecture, among the museum’s collection. They had visibly deteriorated, including cracks, but repairs on them were completed in March.

In recent years, a new theory about these figures has been gaining attention. Their distinctive pose that looks like a dance, with one hand raised and the other lowered, may actually be raising one hand and leading a horse. As one of the figures has a sickle at its waist, some believe that it represents a tool used to cut feed for horses.

The exhibition also presents the meanings and roles of haniwa based on recent research, such as a haniwa in the shape of a ship for carrying the departed soul of a king and a rooster-shaped haniwa for signaling the arrival of dawn.

“I hope visitors will learn about the latest research on haniwa while enjoying the charm of various haniwa pieces,” Kawano said.

The exhibition will run until Dec. 8.

Haniwa imagery reflects changing times

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in Chiyoda Ward is holding an exhibit titled “Modern Images of Ancient Clay Figures” that traces the changing motifs seen in haniwa and dogu, ancient clay figurines from further back in time than haniwa.

The exhibition illustrates how these excavated artifacts have been used to reflect the times in a wide range of fields from the Meiji era (1868-1912) to the present day, including artwork, magazines, textbooks, tokusatsu special effects and animation.

The exhibition reexamines the view of haniwa and dogu within art history, wherein artists such as Taro Okamoto and Isamu Noguchi, who were well versed in Western art, around the 1950s “discovered” the aesthetic value of artifacts that had previously been treated exclusively as archaeological material.

This exhibition emphasizes how haniwa and dogu became resources for boosting Japanese mythology and improving national morale. After the Meiji era through the end of World War II, they were turned to symbols of peace and friendship during the postwar internationalization process.

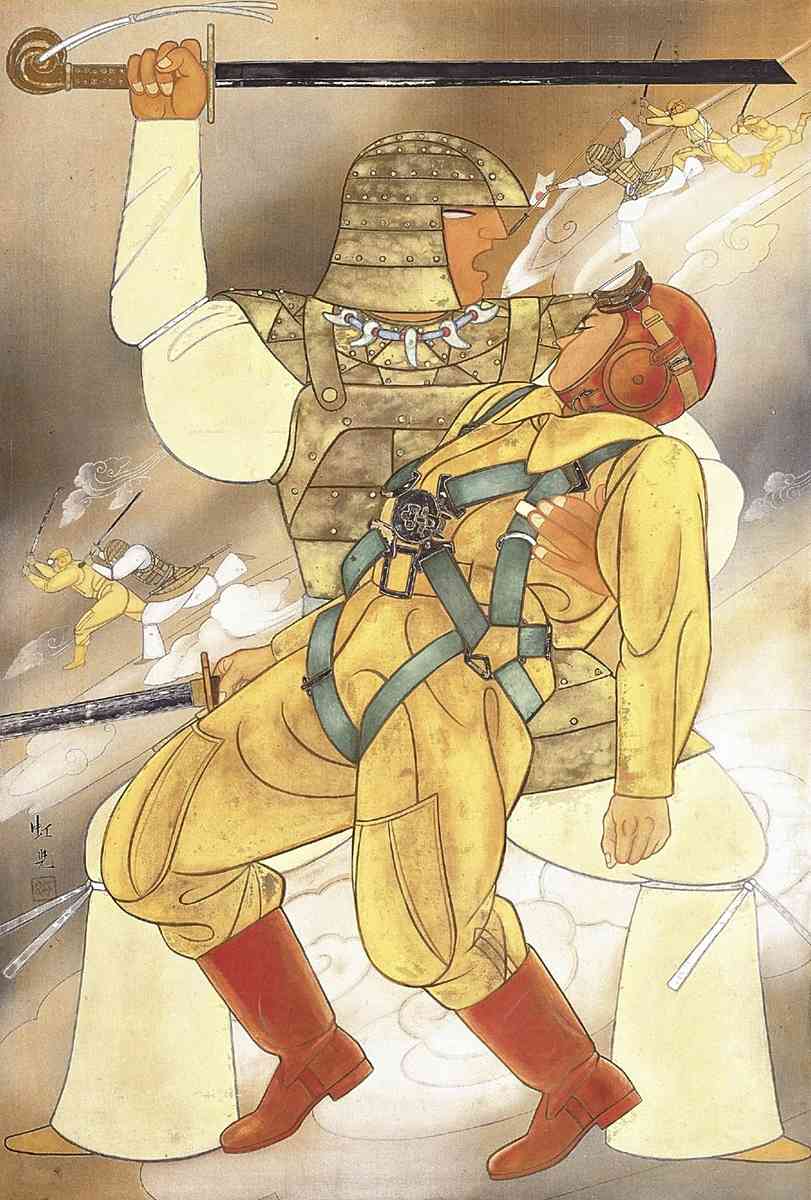

“Heaven’s Warrior” (1943) by Koji Fukiya, from the collection of the city of Shibata, Niigata Prefecture

When the construction of the mausoleum of Emperor Meiji in the Fushimi Momoyama area was attracting societal interest, Kako Tsuji, a Nihonga Japanese-style artist, painted a heartwarming scene of artisans making haniwa, overlapping the early 20th century with ancient times. During the war, the painter and poet Koji Fukiya depicted a brave warrior modeled on a haniwa warrior figure. Facing regulations against abstract expression, the painter Toshinobu Onosato sought to depict his work through a simplified haniwa form.

Photographer Shihachi Fujimoto is also noteworthy for developing a format for presenting the images of artifacts from the prewar to postwar days. He created dramatic effects using black backgrounds and oblique lighting, an approach meant to evoke emotional reactions, which is very different from documentary photography intended to accurately capture details.

Since the war, haniwa and dogu have risen in popularity, being incorporated into various forms of media, such as in the NHK educational program “Oi! Hanimaru.”

Hisaho Hanai, senior researcher at the museum, said: “Artwork can reflect changes in society. I hope this exhibition will give visitors an opportunity to experience the changes in imagery and think about how we see ancient artifacts today.”

The exhibition will last until Dec. 22.

Top Articles in Culture

-

Junichi Okada Wears Three Hats in ‘Last Samurai Standing,’ Serving as Star, Producer, Action Choreographer in Thrilling Netflix Period Drama

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Maison&Objet Kicks off Near Paris with Japanese Lighting Designers’ Installations on Display, Creating Rich Environment

-

Prestigious Japanese Literature Prize Names Toriyama, Hatakeyama as Winners

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time