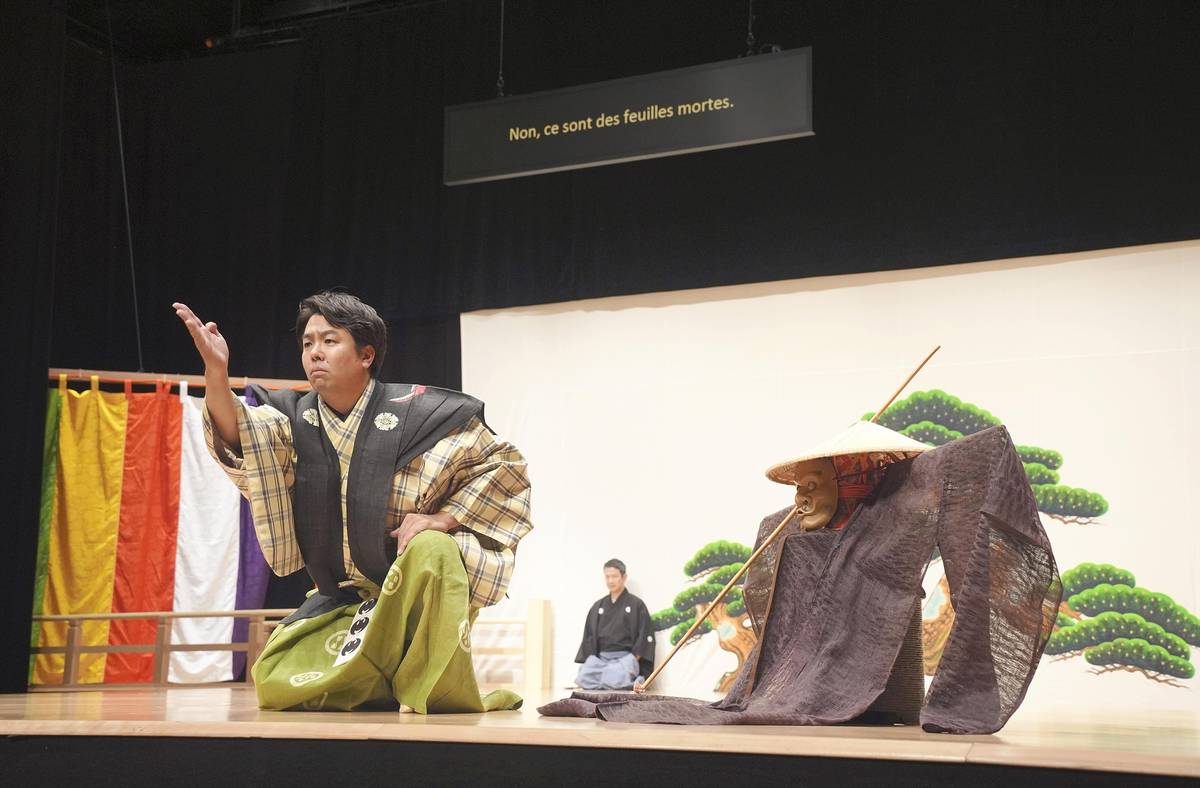

Ezoe performs the lead role in the kyogen play “Uri Nusubito” in Paris.

16:00 JST, November 24, 2024

The 40-year-old Japanese Theater of the Deaf put on a performance of kyogen, a form of traditional Japanese comic theater, in international sign language in France in July.

It was the first time for kyogen to be performed in the universal sign language, enabling the depth of Japanese culture to be conveyed to French audiences prior to the Paris Olympics and Paralympics.

The performances were given in Paris and Reims. The July 4 performance in Reims, northeastern France, was part of the Festival Clin d’Oeil, one of Europe’s largest arts festivals for deaf people. The crowd of about 900 people stomped their feet instead of clapping to show their appreciation. The performance was accompanied by French subtitles.

“It made me happy because I could feel the reverberation of their stomps, a typical reaction from European audiences,” said Satoshi Ezoe, the leader of the Japanese Theater of the Deaf who performed the shite (lead role) in the kyogen play “Uri Nusubito” (The Melon Thief).

Eleven years ago, the company performed a kyogen play in Reims using Japanese sign language, but the audience couldn’t understand the performance in the way the company wanted them to. Ezoe found that frustrating, so this time he explained the plays and the history of kyogen to the audience.

Miyake Ukon, right, trains performers.

“I taught the audience how to express things in kyogen in sign language and the simplicity of the stage. I think they found it easy to follow the performance,” he said.

The company staged the first-ever performance of sign language kyogen in 1983 as part of the World Federation of the Deaf’s World Congress and related theater events in Palermo, Italy. Sign language performances of kyogen have since been taught by Miyake Ukon, a kyogen actor of the Izumi school, and his sons, Miyake Sukenori and Miyake Chikanari, among others. A repertoire of 70 kyogen plays can now be performed using sign language.

Shohei Hasegawa

International sign, which the company used this time, posed difficulties for the performers, as the signs are different from Japanese sign language. For example, in Japanese sign language, “I see” or “I understand” is expressed by placing the palm of your right hand on your chest and brushing down. In international sign language, you make a fist with your right hand and point toward the sky with your index finger. The differences between the two languages come from cultural diversity: For Japanese people, understanding is considered to happen in the heart, while for international sign users, it occurs in the mind.

“Since the hand and body movements go in the opposite direction, I couldn’t get comfortable with it” said Shohei Hasegawa, who played the lead role in the kyogen play “Niwatori Muko” (The Rooster Son-in-Law).

Still, the performers practiced a lot, and their performances were successful.

“If we get the chance to perform abroad regularly, then the audience will be able to appreciate the excitement [of kyogen] more deeply,” Miyake Chikanari said, looking to the future.

A scene from the kyogen play “Niwatori Muko” (The Rooster Son-in-Law) at the Japan Foundation’s Maison de la culture du Japon in Paris on July 6

The company let the performers brush up their kyogen skills and use sign language more expressively. There were times when sign language translations of certain lines were not very clear, resulting in the story and dialogues becoming incomprehensible. However, with time, the kyogen actors gave instructions to the performers and improved their sign language ability.

Miyake Sukenori, center, and Miyake Chikanari, right, train performers.

“Conveying the meanings behind the words and lines that are specific to the classics leads to a deeper understanding [of the plays],” Miyake Sukenori said.

“We’d like to increase the repertoire of [sign language kyogen plays] to 100 plays. We’d also like to take on works that children can participate in,” Ezoe said.

The use of two languages — a sign language and a spoken language — in sign language kyogen performances makes them easier for the audience to understand.

“We’d like to spread the appeal and excitement [of sign language kyogen] not only to deaf people but also to people without hearing loss,” Hasegawa stressed.

Top Articles in Culture

-

Junichi Okada Wears Three Hats in ‘Last Samurai Standing,’ Serving as Star, Producer, Action Choreographer in Thrilling Netflix Period Drama

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Maison&Objet Kicks off Near Paris with Japanese Lighting Designers’ Installations on Display, Creating Rich Environment

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Prestigious Japanese Literature Prize Names Toriyama, Hatakeyama as Winners

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time